Poland has overtaken Germany as the European Union’s biggest generator of electricity from coal, according to a new report by climate think-tank Ember. The data also reveal that Poland generates as much electricity from coal as the rest of the EU (excluding Germany) combined.

The findings come as Polish officials reconsider their country’s dependence on coal, which currently accounts for around 80% of Poland’s power – by far the highest proportion in the EU.

As other countries move in a greener direction, and EU regulations make coal an increasingly costly energy source, Poland has also begun slowly to embrace cleaner forms of energy.

The report from Ember, published yesterday, analyses Europe’s electricity system based on aggregated grid data from the European Network of Transmission System Operators.

It finds that, in the first half of 2020, Poland generated 50.5 terawatt hours (TwH) of energy from coal (hard coal and lignite combined). That saw it overtake Germany, on 47.7 TwH, for the first time. It also puts Poland only narrowly behind the remaining 25 EU countries combined, on 51.5 TwH.

Poland is now “in a very embarrassing position”, says Dave Jones, senior electricity analyst at Ember and one of the report’s co-authors.

“Poland has been hiding behind Germany’s obsession with coal for decades, and Germany’s 2038 phase-out [plan] has put little pressure on Poland to act,” says Jones. “But Germany’s coal is collapsing faster than anyone expected.”

“It was surprising that coal generation fell so quickly in other countries in 2020,” add Jones, who cites the fall in electricity demand during the coronavirus pandemic.

Ember found that, as in every other country, coal generation did fall in Poland, by 12%. But it puts this down mainly to cheaper electricity imports from neighbouring countries rather than rising renewables or lower demand.

The report describes Poland as now being “out on a limb” in terms of coal generation, with no concrete coal phase-out plans – unlike in other EU countries, such as Germany.

This is despite recent challenges faced by the country’s ailing coal sector, including a fall in domestic power production and EU climate regulations forcing costly modification to plants.

There are, however, signs that change is slowly taking place. Last month, documents revealed that Polish state energy group PGE is planning to shut down parts of Bełchatów, the largest coal power plant in Europe and the EU’s biggest single source of CO2 emissions.

Recent comments by representatives of PGE have suggested the company has a “phase-out plan” to withdraw from its entire coal and lignite operations within 20 to 25 years. Maciej Burny, the director of the firm’s Brussels office, told S&P Global Platts that the company needed to “either change now or never”.

However, he added that, if Poland tried to phase out coal more quickly – and in line with strict EU emissions targets – PGE’s profitability and ability to finance renewable and gas-fired generation could take a hit.

Yet increasing costs resulting from EU climate policies have themselves put pressure on the Polish coal sector, reports Business Insider. Further EU regulations coming into force in the future will make Polish coal mines and power stations even less cost-effective.

Yet the Polish authorities face an additional hurdle in any potential energy transition in the form of a powerful mining lobby.

However, the Ember report says there is a “clear way out” for countries like Poland and the Czech Republic, Europe’s third largest coal generator, if they accept EU funding to help them transition away from coal and turn to renewable investment.

Analysis from Enervis also suggests that replacing power plants with renewable gas-assisted energy sources could be possible before 2030 – and would save 4 billion zloty, which would otherwise have to be spent on the modernisation and maintenance of coal power blocks, reports Gazeta Wyborcza. It could also allow Poland to benefit from EU funds supporting greener energy alternatives.

Poland is currently the only member state not to have committed to the EU’s goal of achieving climate neutrality by 2050. According to the new EU budget agreed this week, Poland can access only 50% of the funds intended for green energy transition unless is signs up to the target.

The Ember report shows that Europe as a whole is moving towards renewable alternatives. Although progress has slowed due to COVID-19, countries are demonstrating they can “cope with record shares of wind and solar on the electricity grid” with renewables proving “more resilient than fossil fuels in the face of this crisis.”

Poland has also embraced more renewable energy recently, particularly from solar, with the country’s solar capacity increasing by 900MW last year.

According to a report from AltEnergyMag earlier this year, Poland has become the fifth largest producer in Europe, almost quadrupling its solar capacity in one year. State funds are also subsiding micro-PV systems through the government’s “My Electricity” programme.

Wind energy, which before 2015 was expanding rapidly in Poland but was then tightly restricted following the arrival of the conservative Law and Justice (PiS) government that year, is now looking more hopeful again.

The International Energy Agency estimates that Poland will increase its renewable power capacity by 65% from 2019 to 2024, mostly from onshore wind farms, writes Bloomberg. There are also plans for up to 10GW of offshore wind on the Baltic coast by 2035.

The biggest role in increasing the proportion of renewables in the Polish energy balance has been played by private energy companies and prosumer firms, which together built 81% of all renewable power installed in 2013-2019.

By contrast, the contribution of the public sector and state-owned energy concerns to building renewable energy sources in these years was under 15%.

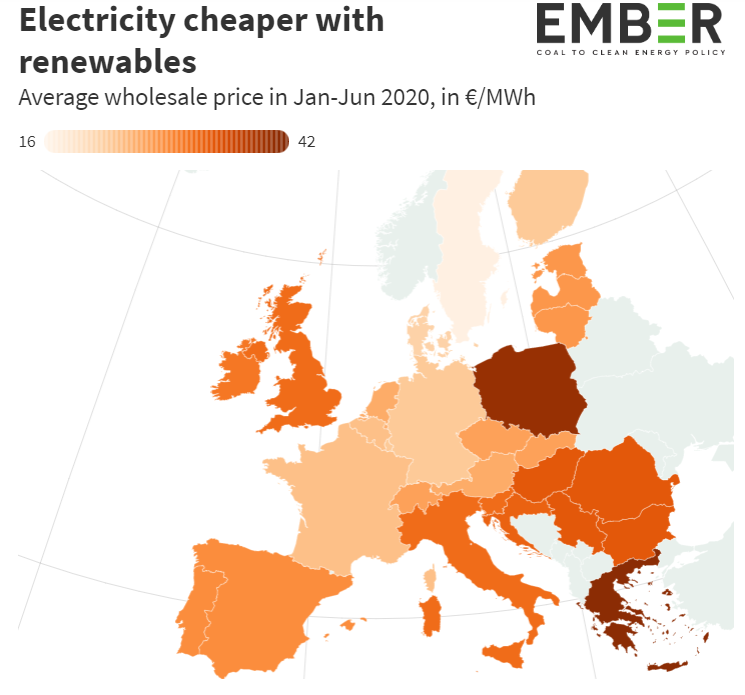

“Sure Poland has built some wind and solar, but with 14% of its electricity from [these sources], it’s well behind the European average of 22%, and that shows in the high wholesale electricity prices, which are second only to Greece,” says Jones.

“A lack of ambition is holding Poland back. It needs to think bigger and instigate some urgency to its electricity transition.”

Juliette Bretan is a freelance journalist covering Polish and Eastern European current affairs and culture. Her work has featured on the BBC World Service, and in CityMetric, The Independent, Ozy, New Eastern Europe and Culture.pl.