By Filip Mazurczak

Hundreds of classic Polish films have been digitally restored and made available online for free, with English subtitles, as part of a project funded by Poland’s culture ministry and the European Union.

The new service offers a unique opportunity for international audiences to get a taste of one of the world’s most important and influential national cinematic canons.

Below we present a curated list of ten works available at 35mm.online that provide a chronologically, thematically and tonally diverse sample of some of the finest works of Polish culture in the twentieth century.

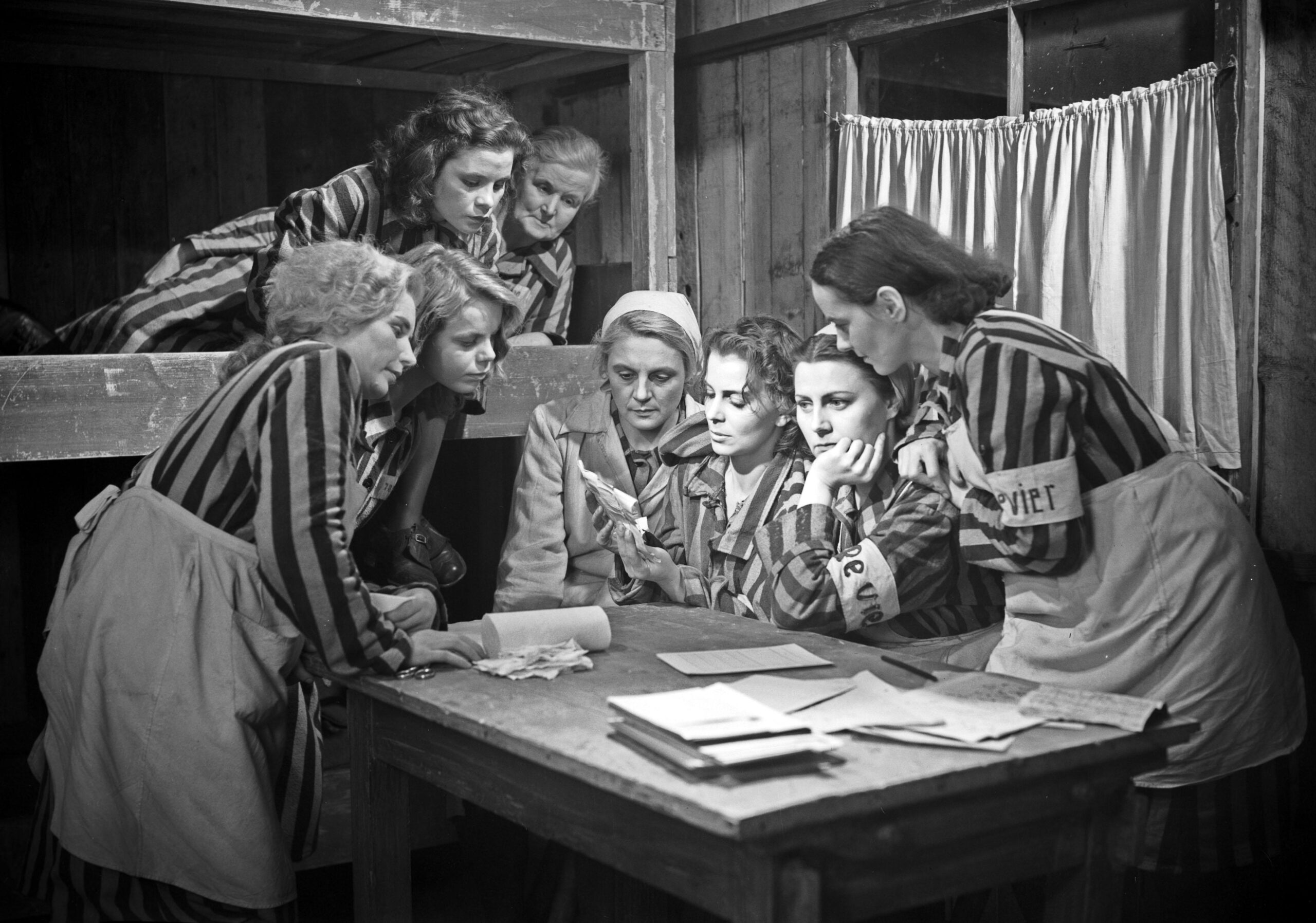

The Last Stage, dir. Wanda Jakubowska, 1947

Although countless films have been made about the Third Reich’s crimes, The Last Stage was one of the first (if not the first). This autobiographical work was directed by Wanda Jakubowska, herself a former inmate at Auschwitz-Birkenau due to her activity with Poland’s communist resistance, and was filmed at the former Nazi-German camp mere months after its liberation. The film tells the story of a group of female inmates from various occupied countries who start a resistance movement in the camp.

While some of the acting in The Last Stage seems hokey and the film’s blatant communist propaganda has not aged well, it contains many unforgettable images of everyday life and death in the most infamous Konzentrationslager: a German doctor administering a lethal injection to a Polish newborn; a Jewish woman who has just arrived at the camp being comforted by her daughter, who claims that if the Germans wanted to kill them they would have sent them to the forest; and scenes of emaciated, dirty inmates in rags interspersed with images of the ruddy SS-men and women running the camp (including an obese commandant, who looks strikingly different from his victims) drinking fine wines, joking, and waltzing to Strauss.

Knights of the Teutonic Order, dir. Aleksander Ford, 1960

Knights of the Teutonic Order is an adaptation of the novel by Henryk Sienkiewicz, who wrote of the Poles’ past glories while their nation was under foreign domination. A classic historical romance, Knights of the Teutonic Order tells of the 1410 Battle of Grunwald during which Polish-Lithuanian forces defeated the Teutonic Knights, a German order of hospitallers founded during the Crusades that terrorised the Polish population in Pomerania and used violence to convert the pagan tribes of the Baltics to Christianity.

Released just fifteen years after the end of the Second World War, in which millions of Polish citizens had lost their lives at German hands, the film’s Teutonic Knights are unmistakably depicted as the predecessors of the Nazis; before riding into battle, they chant: Heil! Heil! Heil!

Knights of the Teutonic Order is easily the most popular Polish film of all time: at a time when Poland’s population numbered 32 million, it sold 35 million tickets. More than a thousand extras were employed in the making of the film, and the epic battle scenes were very realistic; during filming, many extras were trampled by horses.

Despite his enormous success, the film’s director, Aleksander Ford, met a tragic end. Having been expelled from Poland during the communist regime’s anti-Jewish purge in 1968, Ford moved to Israel and later the United States. His only film made abroad was a critical and commercial flop. Unable to find meaningful artistic employment abroad and abandoned by his wife, Ford committed suicide in 1980.

Passenger, dir. Andrzej Munk, 1963

Passenger clocks in at only fifty-nine minutes; filming was interrupted by director Munk’s tragic death in a car accident.

The unfinished film deals with the topic of willful amnesia in the aftermath of war crimes. The film has two female protagonists, Marta, a Polish political prisoner at Auschwitz-Birkenau, and Liza, a German SS guard and Marta’s tormentor.

On a transatlantic cruise, Liza spots Marta, which leads her to give her account of what had happened at Auschwitz to her husband. Liza emphasizes how well she had treated Marta; the only reason why Marta had survived, she claims, was because of her benevolence. Marta, however, remembers things differently.

While incomplete, Passenger is a powerful testimony to how accomplices to evil often undertake great pains to rewrite the past; watching it, I was reminded of the constant denials of Leni Riefenstahl, Hitler’s propaganda filmmaker, that she knew anything about Nazi atrocities despite published photographic evidence demonstrating she was present during the executions of civilians in German-occupied Poland.

Our Folks, dir. Sylwester Chęciński, 1967

“Kargul, come to the fence” – this is one of the most-quoted lines from Polish film.

Our Folks tells of the constant conflict between two families, the Karguls and the Pawlaks, who were expelled by Soviet authorities in formerly Polish areas and resettled in Poland’s western “Recovered Territories.” The two neighbours get along about as well as Felix Unger and Oscar Madison in Neil Simon’s The Odd Couple but must bury their hatchet when their children marry.

While this is one of many takes on the familiar Montagues vs. Capulets plot, the film has had an enormous impact on Polish society and presents the traumatic family histories of millions of forcibly resettled Poles in an amusing way.

The Sandglass, dir. Wojciech Jerzy Has, 1973

If you are fond of Bunuel, Lynch, and Jodorowsky, you will love The Sandglass. A loose adaptation of the short story of the same title by Bruno Schulz, one of the great masters of the Polish language in the twentieth century (in English, it has been published in The Street of Crocodiles and Other Stories), it tells the story of Józef, who comes to the dilapidated Hourglass Sanatorium, filled with more cobwebs than Miss Havisham’s room, to see his dying father. Although Józef’s father is dead elsewhere, he is still alive in the sanatorium, its resident physician explains, because there, time is an unspecified interval behind the rest of the world.

Whereas Schulz’s prose is magical realist, Has’ adaptation is uncompromising surrealism filled with a bleeding mannequin of the Austrian emperor, maggots, and plenty of eyeballs. However, it would be very superficial to interpret the film as merely a trippy Daliesque fever dream. When Józef puts on a magical Austro-Hungarian helmet, he is taken back to the Habsburg partition of southeastern Poland.

In addition to Austrian officials and military officers, everywhere are Jews – dancing, praying, and squabbling. Undoubtedly, Has is trying to evoke the tragedy of the disappearance of the civilization of Galician Jewry. It cannot be insignificant that the film was released five years after the communist regime’s antisemitic campaign forced thousands of Polish Jews to emigrate.

Talking Heads, dir. Krzysztof Kieślowski, 1980

Talking Heads is a unique psychological and philosophical experiment in which Kieślowski approached dozens of strangers, ranging in age beginning with a mute infant and ultimately progressing to a centenarian, asking them who they are and what they most want.

The two youngest children say they respectively most want nothing and to be a Syrena car, while the centenarian says with a laugh that she simply wants to live longer. Teenage respondents express insecurities; one man says he is still young and so still has ideals and is not a cynic; another wants change in his life, but cannot put his finger on what such change entails.

Although shot in 1980, a very eventful year for communist-ruled Poland, the responses recorded in Talking Heads are universal; many of them could probably be heard today if a similar experiment were performed.

Blind Chance, dir. Krzysztof Kieślowski, 1981

Blind Chance shows how radically different the life of Witek, a university student played by Bogusław Linda, one of Poland’s finest actors, would have been if he had boarded a train or if he had just missed it.

In one scenario, he is a prominent anti-communist dissident, but in another becomes a snitch for the regime. It is not insignificant that Witek’s father took part in the 1956 protests, while his aunt is a zealous communist (scenes depicting tortures by communist functionaries made it to a censor’s cutting room table and have never been recovered). Perhaps Kieślowski is suggesting that most people in a totalitarian state are torn between the pressures of resistance and compliance, while their attitude towards the regime often depends on their circumstances rather than their moral rectitude.

More broadly, Blind Chance deals with ancient philosophical questions about the degree to which people have agency over their fate or if they are mere playthings of the gods or history.

The film’s structure was borrowed by the German director Tom Tykwer in his Run, Lola, Run. Tykwer was a great enthusiast of Kieślowski, having adapted his screenplay Heaven, part of an intended Dantean trilogy based on hell, purgatory, and heaven which Kieślowski was unable to direct due to his premature death.

Man of Iron, dir. Andrzej Wajda, 1981

Man of Iron is a rare combination of a dramatic film featuring historical figures as history was unfolding. Released during the “carnival” period of Solidarity, when the non-violent workers’ movement posed a major threat to Soviet hegemony over Eastern Europe which led to a brief liberalisation of the regime before the imposition of martial law, the Oscar-nominated film chronicles regime journalist Winkel’s attempts to infiltrate Solidarity’s strike committee and find materials compromising one of its leaders, the son of the model bricklayer Mateusz Birkut, the protagonist of a previous Wajda film, Man of Marble.

Featuring actual Solidarity leaders such as Lech Wałęsa and Anna Walentynowicz and depicting the communist militia’s brutality towards striking workers, Man of Iron is an inspiring and moving tribute to the movement that helped, eight years later, to bring down the communist regime.

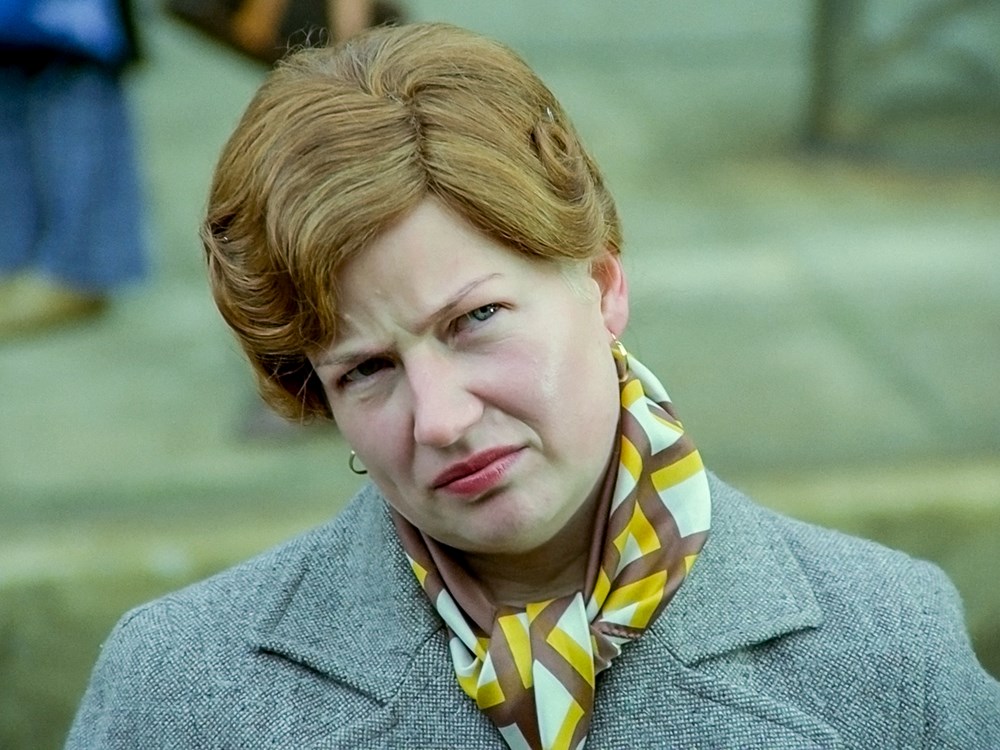

The Emergency Exit, dir. Roman Załuski, 1982

Set in a village in Lower Silesia, The Emergency Exit tells of the head of the commune (a function akin to a mayor) whose daughter is impregnated when a group of university students visits. Fearing scandal, the commune head sends her husband to Wroclaw, the nearest big city, to hire someone to play her daughter’s fiancée, marry her, and later divorce the girl, all of which will be generously reimbursed. Unwittingly, her husband hires a con man just released from prison.

Such a setup provides great potential for laughter, of which director Roman Załuski as well as stars Bożena Dykiel as the domineering wife and village leader and Jerzy Turek as her bumbling husband make excellent use.

Our God’s Brother, dir. Krzysztof Zanussi, 1997

Based on a 1950 play by Karol Wojtyła, the future Pope John Paul II, Our God’s Brother co-stars Christoph Waltz, more than a decade before he would become a household name thanks to Inglorious Basterds.

Krzysztof Zanussi’s films often deal with existential and metaphysical themes, and Our God’s Brother is one of his best. It tells the true story of Brother Albert Chmielowski, a successful 19th-century painter who lost his leg in one of Poland’s many ill-fated insurrections against Russia and suffered the pangs of unrequited love for the famous Polish theatre actress Helena Modrzejewska.

Disturbed by the plagues of homelessness and poverty in Kraków, Chmielowski, now a Catholic saint, renounced his life of privilege, became a Third Order Franciscan, and began to take the homeless into his apartment, eventually building an international chain of homeless shelters.

Most interesting are the conversations between Chmielowski and fellow painter Maksymilian Gierymski (Waltz), a proto-Randian capitalist who believes that the poor are simply lazy, as well as “the Stranger,” played by Wojciech Pszoniak, one of Poland’s finest actors, a figure modelled after Lenin who proposes violent revolution as the solution to poverty.

Unlike the ruthless free market or hateful communist revolution, Chmielowski proposes Christian charity as the solution. These fascinating dialogues recall the disputes between Herrs Naphta and Settembrini in Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain.

All image credits: 35mm.online (screenshots)