Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Aleks Szczerbiak

Although the right-wing candidate’s presidential election win initially emboldened the opposition, it increasingly turned in on itself as the government stabilised its position. Nonetheless, the conservative camp still appears on track to win a majority at the next election if the president can help reconstruct the broad alliance that secured his victory.

Emboldening the opposition

In December 2023, a coalition government headed up by liberal-centrist Civic Coalition (KO) leader Donald Tusk took office following eight years rule by the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) party, currently the main opposition grouping.

However, the surprise victory of PiS-backed candidate Karol Nawrocki in the May-June presidential election scuppered the Tusk administration’s plans to align all branches of state power so that it could push through its policy agenda and elite replacement programme.

The government lacks the three-fifths parliamentary majority required to overturn a presidential veto, so faces continued resistance from a hostile president who can effectively block many of its key reforms for the remainder of its term of office, which is scheduled to run until the next election in autumn 2027.

Just as importantly, Nawrocki’s victory transformed Poland’s political dynamics, as a result of which the governing coalition found itself severely weakened and on the defensive. The election was widely seen as, above all, a referendum on the Tusk government and opportunity to channel discontent with the failure to deliver on policy pledges that helped bring it to power.

Karol Nawrocki has sought to redefine Poland's presidency and become the figurehead of the right-wing opposition.

So far, it is working, but questions remain over what his end goal is and whether these tactics will get him there, writes @danieltilles1 https://t.co/TNDRGGv2QT

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 22, 2025

This feeling of a radically new political landscape was reinforced when Nawrocki took office in August and it became clear that he would be an assertive president keen to carve out a role for himself as an independent actor. With a blaze of presidential vetoes and legislative and foreign policy initiatives, Nawrocki quickly became Poland’s most popular politician.

At the same time, it was also obvious that the government was, initially at least, completely unprepared for his victory, raising the possibility of an early election. As a consequence, Nawrocki’s victory also emboldened the right-wing opposition, which saw it as a pivotal moment providing a clear pathway to regaining full power following an inevitable victory at the next parliamentary election.

Turning in on itself

In fact, the Tusk government stabilised its position and launched a counter-offensive to shift the political dynamics back in its favour. At the same time, although Nawrocki’s election-winning coalition successfully brought together supporters of various right-wing political groupings, since then they have increasingly turned on each other.

In particular, relations between the two leading right-wing parties – PiS and the radical right free-market Confederation (Konfederacja), whose presidential candidate Sławomir Mentzen finished a strong third with 14.8% of the first round votes – have become increasingly strained.

PiS was politically re-energised but also became extremely complacent, interpreting Nawrocki’s victory as a signal that it was capable of winning the next parliamentary election on its own. The party started to focus its fire increasingly on Confederation rather than the government, issuing a challenge for Mentzen to rule out a future coalition with Tusk.

Opinion polls show that @donaldtusk's ruling party has pulled ahead of its main rival, PiS

However, the position of Tusk's coalition remains precarious, and the government's fundamental problems and weaknesses have not gone away, writes @AleksSzczerbiak https://t.co/3cPqac4pqE

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 11, 2025

Confederation refused to do this as it would undermine its identity as an anti-establishment grouping that views both main parties as two sides of the same corrupt “duopoly”. Mentzen responded by calling PiS leader Jarosław Kaczyński a liar, boor and political gangster; although other Confederation leaders, notably Krzysztof Bosak, leader of its nationalist wing, were much more restrained.

Moreover, the emergence in October of a high-profile corruption probe into a suspicious sale of strategic state-owned land designated for the planned Central Communication Port (CPK) “mega-airport” and transport hub, one of the PiS government’s flagship infrastructure projects, to a private entity for a fraction of its market value shortly before it left office in 2023 was very damaging for the party.

This was followed by the laying of 26 criminal charges against former PiS justice minister Zbigniew Ziobro, who was accused of leading an “organised criminal group” that allegedly misused around 150 million zloty (€35.5 million) from the so-called Justice Fund (designed to assist victims of crime) for political patronage and unlawfully financing the purchase of the Pegasus spyware system.

Although criticised by government opponents as a politically motivated witch hunt or displacement activity, this completely overshadowed a PiS programmatic convention meant to launch the party’s autumn political offensive. It also gave the Tusk administration tangible examples to underpin its narrative that the previous government was corrupt and misused state power.

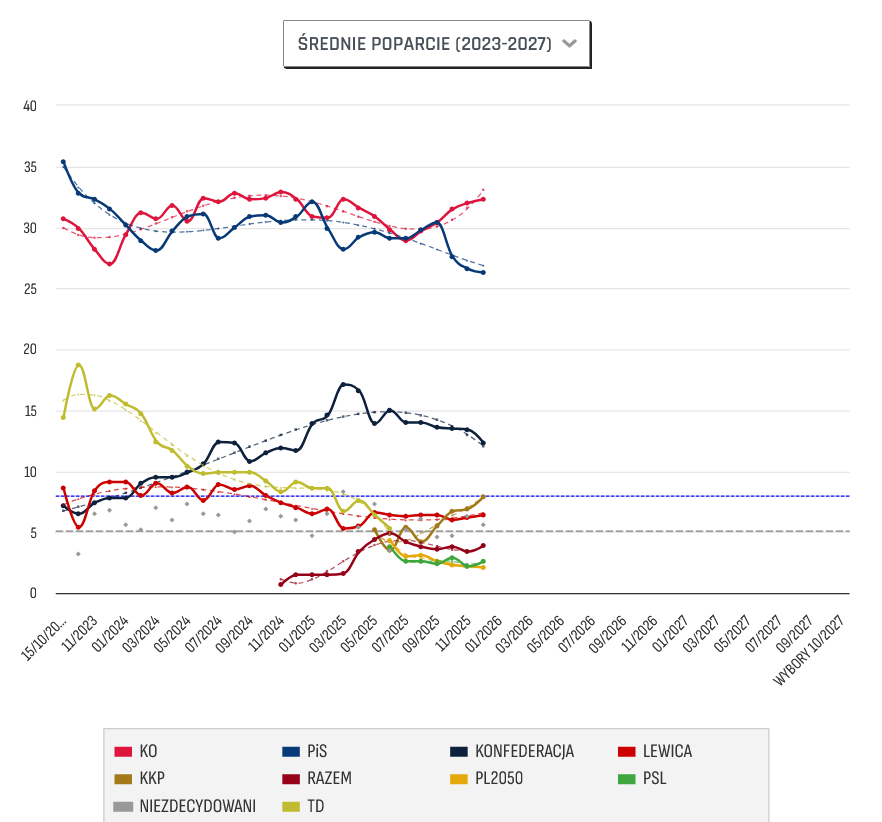

According to the Politico Europe aggregator of Polish opinion polls, PiS saw its support drop from 31% in June to 28% in December, falling behind KO, which is currently averaging 34%.

Monthly average support in polls tracked by aggregator ewybory.

Different social bases

Apart from letting the Tusk government off the hook, the two right-wing groupings’ political strategies were both based on false premises.

On the one hand, following Nawrocki’s victory PiS appeared to believe that, by portraying Confederation as a potential future collaborator with Tusk, it could alienate the party from its “anti-system” base, and tap into voter disillusionment with the government to secure the 40% vote threshold traditionally needed to win an outright majority.

Confederation, on the other hand, believed that, by presenting the KO-PiS duopoly as two sides of the same stagnant establishment and positioning itself as the only truly “anti-system” alternative, it could replace PiS as the dominant force on the Polish right.

In both cases, this ignores the fact that the two parties appeal to very different social constituencies, reflected in their varying approaches to socio-economic policy.

While the Catholic church remains a totemic force in Polish society, the relationship between parties and religion in post-communist Poland is a complex one and continues to evolve, writes @AleksSzczerbiak https://t.co/Hpaho3W05b

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) November 22, 2025

PiS relies heavily on less well-off, less well-educated, older voters living in rural areas and smaller towns, who are also more socially and culturally conservative and religiously devout. These voters typically favour large-scale fiscal transfers and social welfare programmes.

Confederation, on the other hand, enjoys particularly high levels of support among younger voters who generally view PiS as a part of the stagnant “old guard” duopoly. These voters often feel frustrated with the apparent “glass ceiling” of vested interests and corrupt networks that stifles opportunities for them, and do not see state support and social spending as the solution to their problems but rather favour radical free-market economics.

Confederation’s younger voters tend to be more secular and quite socially liberally, although they also often see the “woke” left as a greater threat to their personal freedom than the religious right.

PiS increasingly divided

On top of that, PiS’s internal cohesion, and possibly even survival as a unitary political grouping, is threatened by increasingly bitter open factional divisions. These conflicts have been a constant feature of PiS but have become more public and pronounced as a result of the progressive weakening of Kaczyński’s authority as party leader.

Kaczyński has been the crucial key source of unity within PiS as the ultimate arbiter balancing power between the rival camps. However, although his leadership remains unquestioned, Kaczyński’s influence is steadily weakening and the party splitting into several competing camps.

The more hardline-conservative faction grouped around MEP Tobiasz Bocheński (often referred to in the Polish media humorously as the maślarze or “butter-makers”) has gained significant momentum in recent months, being given control of the party’s 2027 parliamentary election programme.

This faction is more Eurosceptic and advocates a more right-wing agenda that includes pushing ahead with radical state reconstruction and promoting a conservative vision of national identity and traditional values. Politicians previously linked to Sovereign Poland (SP), a small hardline right-wing conservative party led by Ziobro which was formally re-integrated into PiS last year, are also aligned with this faction.

The modernising-technocratic wing led by former prime minister Mateusz Morawiecki also have strong conservative values and have at times been very critical of Poland’s post-1989 establishment, but emphasise economic competence and boosting Polish prosperity as a more effective way of appealing to voters less influenced by traditional institutions such as the Catholic church.

Although at one point Kaczyński backed Morawiecki, viewing him as better equipped to deliver socio-economic success and manage international relations, this faction has become increasingly marginalised.

Although Morawiecki and his supporters publicly maintain their loyalty to the party, the tension between the two factions has become so severe that some insiders suggest they are working actively towards each other’s marginalisation or exclusion ahead of the next election.

The rise of Grzegorz Braun

Another factor significantly complicating efforts to unite the Polish right has been the rise of the Confederation of the Polish Crown (KPP) led by Grzegorz Braun, who was expelled from the main Confederation alliance in January.

Braun’s splinter party has surged since his unexpected fourth place in the presidential election with 6.3%, notably picking up the support of many disillusioned former PiS voters. According to Politico Europe, it is averaging 8% compared with 12% for Mentzen’s grouping, and in some polls even overtaking it, demonstrating a growing public appetite for even more radical right-wing anti-establishment stances.

Braun’s platform encompasses: opposing the so-called “Ukrainisation” of Poland, anti-Jewish stances including claims that the current Auschwitz gas chambers are fake, radical anti-EU rhetoric that goes well beyond PiS’s anti-federalism, and sometimes violent provocations such as attacking a Hanukkah celebration in parliament.

But while this appeals to a specific radicalised core electoral base, it is viewed as toxic by more moderate conservative and centrist Poles.

A new poll shows the party of far-right leader Grzegorz Braun reaching third place for the first time, with support of 11%

The finding continues a dramatic recent rise for Braun, who is currently on trial for attacking a Hanukkah celebration in parliament https://t.co/XeKwJy6YLG

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 17, 2025

The problem for the Polish right is that currently it cannot return to power without Braun’s party’s support. However, his radical policies and actions mean that any hint of a formal alliance will be leveraged by the Tusk government to discredit the entire conservative camp as unfit for office.

A possible link-up with Braun’s party could, for example, emerge as an issue around whether to agree a unified right-wing electoral front for the Senate, Poland’s less powerful second parliamentary chamber. The Senate is elected by the first-past-the-post system that favours large, unified electoral blocs such as the “Senate pact” (pakt senacki) that helped the current ruling coalition secure a majority.

Many commentators argue that a key factor explaining why Braun has picked up former PiS voters is that the party has not atoned sufficiently for its perceived strategic and moral errors during its period of office.

These, they argue, include: surrendering too much sovereignty to the EU, failing to advance Polish interests sufficiently in relations with Ukraine, focusing too much on securing short-term political control rather than building durable reformed institutions in areas such as the judiciary, and turning into a “new elite” that forgot its anti-system roots.

Indeed, in many ways the presidential election result masked the fact that Nawrocki’s 29.5% of first-round votes was actually less than the 35.4% PiS secured in the 2023 parliamentary election and the party’s lowest vote share for 20 years.

Nawrocki is the key?

Nonetheless, in spite of its post-presidential election drift, recent projections suggest that, overall, the right-wing camp still appears most likely to win a majority of seats in the new parliament because the smaller governing coalition partners are struggling to cross the electoral representation threshold.

Moreover, combining social welfare commitments with a harder line on Ukraine and more pronounced Euroscepticism, Nawrocki demonstrated a formula for attracting those right-wing voters who reject PiS, capturing around 90% of both Mentzen and Braun’s first-round voters.

Although he was PiS’s presidential candidate, Nawrocki operates as an independent authority outside of Kaczyński’s direct control, and, some argue, is actually ideologically closer to Confederation.

As a figure who straddles the broad right-wing camp, Nawrocki is thus potentially the key figure who can reconstruct the broad, election-winning right-wing coalition that he brought together so successfully in the presidential run-off.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Łukasz Błasikiewicz/KPRP