By Alicja Ptak

In 1990, eight years after the construction of what was supposed to be Poland’s first nuclear power plant began, and following years of fierce protests, the project in the village of Żarnowiec near the Baltic coast was finally abandoned.

“The nuclear plant in Żarnowiec is an unnecessary investment for the Polish energy system in the horizon of 10 to 20 years,” announced Tadeusz Syryjczyk, the then industry minister in Poland’s first post-communist government. “After all, it is not at all certain that nuclear power will be needed.”

In the three decades that have passed since then, the history of nuclear power in Poland has almost come full circle. The present government is again pressing ahead with long-term plans to build the country’s first nuclear plants, and is again facing some local resistance.

But this time, by contrast, the plans look set to succeed, with the need for nuclear much stronger and clearer in the context of Poland’s plans to decarbonise its energy sector and move away from Russian energy resources.

This month will see a key moment in the process, with Poland shortly set to choose an international partner to provide technology and financing for its first nuclear plant, which is supposed to start operating in 2033. There are three bidders – the United States, France, and South Korea – all of which have been courting Poland’s government.

How will Poland make a choice?

Despite nearly tripling the share of renewables in its energy mix during the past decade, Poland still remains by far the European Union’s most coal-dependent country, with 71% of its electricity produced from burning this fuel.

The ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party – long friendly towards the coal sector – has in recent years, under EU pressure, gradually accepted the need to move towards lower- and zero-emissions power sources. This has included a rapid expansion of solar energy as well as plans for offshore wind power in the Baltic, but also the adoption, in 2021, of plans to construct six nuclear reactors by 2043, with a total installed capacity of 6 to 9 GW.

Three of the reactors will be located in the north of Poland, probably in the coastal municipality of Choczewo, which has been named as the preferred location pending a decision by the environmental protection agency. The remaining three reactors are to be built somewhere in central Poland.

Those plans have been lent extra urgency by events this year, with the energy crisis prompted by Russia’s war in Ukraine reinforcing the need for stable, reliable energy sources that are less dependent on supplies from other countries.

Speaking to Notes from Poland, deputy climate minister Adam Guibourgé-Czetwertyński indicated that Warsaw was considering accelerating the schedule.

“We can start work on the selection of the second site earlier than we had anticipated,” he says. Originally, the search for the site for the second set of reactors was to begin only once work at the first location is launched.

Another thing the government will consider to speed up work on the nuclear project is choosing different suppliers of technology for each site, adds Guibourgé-Czetwertyński.

The news of the potential use of the two technologies was welcomed by France, which sees itself as an ideal partner for Poland’s nuclear plans given the two countries’ already existing partnership within the European Union.

“France and Poland are and will remain close allies in defending the contribution of nuclear power to the decarbonisation of the EU energy mix, and thereupon to the strengthening of the EU energy independence and sovereignty,” Philippe Crouzet, the French government’s high representative for cooperation with Poland in nuclear energy, told Notes from Poland.

“The sooner the second site for the construction of the new reactors is identified, the better,” he adds. “This meaningful choice will enable rapid decarbonisation of the Polish energy mix.”

Despite France’s optimism, US technology has long been considered a frontrunner by many experts. Poland’s transatlantic ties – already strong under the PiS government – have strengthened further during the war in Ukraine. Last month, the US formally handed over an offer to Poland to build all six of its planned reactors.

But Aleksander Śniegocki, head of the Reform Institute, a public policy think tank in Warsaw, says that, if it was up to him, he would bet on Korean technology.

The Koreans “have been quite active and efficient in building these power plants in recent years,” whereas “the French and Americans have big problems when it comes to delivering projects on time”.

Why are the first three reactors set to be built in Choczewo?

Choczewo, a municipality around 80 kilometres west of Gdańsk, is a holiday destination for those who love the sea but hate the crowds. The small villages surrounding it remain largely focused on farming and small-scale tourism.

But all of that would change if, as expected, the sleepy settlement becomes home to Poland’s first nuclear plant – the first power station of this size anywhere in northern Poland.

If three reactors, with a total installed capacity of no more than 3.75 GW, end up being built here, as well as the planned offshore wind farms and largest photovoltaic farm in Central and Eastern Europe, this tiny municipality, with a population of 5,500, would generate 12% of Poland’s electricity needs, its mayor, Wiesław Gębka, tells Notes from Poland.

When asked what he thinks about the planned power plant, Gębka says that, as a private individual, he is resistant because he moved to Choczewo to be closer to nature. However, as a public official, he wants the best possible solutions “for the municipality and the country”, which “has an energy problem”.

Gębka, a former businessman who has been Choczewo’s mayor for 12 years, is counting on construction of the plant – which will involve between 8,000 and 12,000 workers – bringing his community riches.

“If it has to be built here and they are going to destroy the Choczewo municipality, then at least we should make some money out of it,” he says. Both the mayor and Poland’s climate ministry say that polling shows a majority of local residents support construction of the plant.

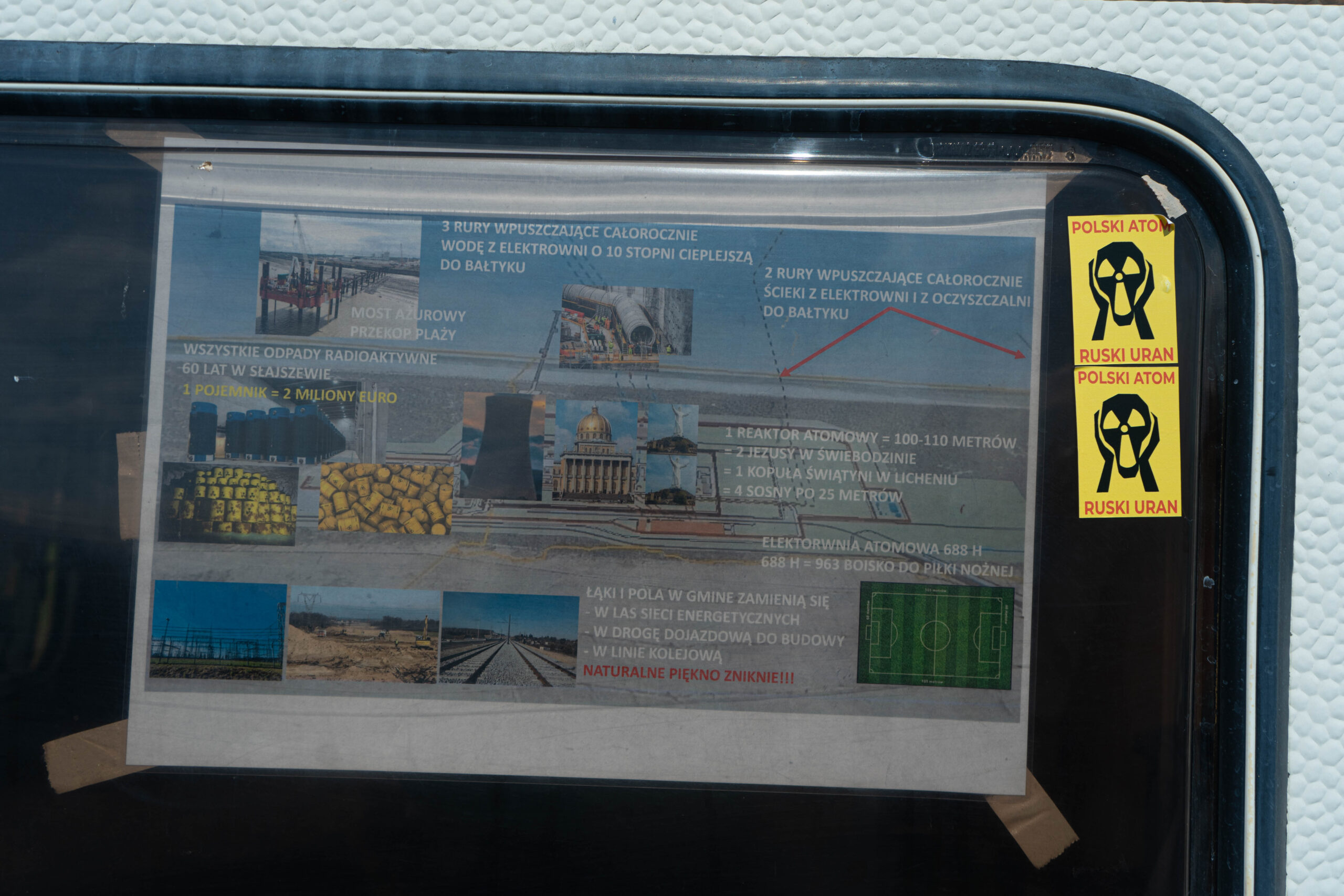

But, visiting the area, it is clear many are not enthusiastic. Choczewo is dotted with anti-nuclear banners on fences. Katarzyna Zacharewicz, a 62-year-old farmer and business owner from Słajszewo, a village within the bounds of the Choczewo municipality that would be the closest to the planned power plant, fears her business will inevitably suffer once construction begins.

Zacharewicz has been running a small farm and bed and breakfast with room for barely more than a dozen guests for nearly 30 years. She says that during that time she has seen her guests coming to Słajszewo year after year, but that they now say they will stop coming once construction of the power plant begins in 2026.

“What we built here cost us a lot of sacrifices. We didn’t go on any holidays, it was just work, work, work. And it is sad because we were building all this to leave for future generations,” she says.

Most difficult for Zacharewicz, who has been fighting since 2008 to prevent a nuclear power plant from being built in the area, is the uncertainty.

The Polish government has still not approved the plan to compensate residents and businesses in the surrounding villages, so Zacharewicz feels that, once the construction begins, her life’s work will have been wasted, and she will be left with no way to make a living and nothing to pass on to her two adult sons.

An anti-nuclear sticker on a sign pointing to the beach in Choczewo.

However, her resistance to nuclear power – similarly to some other Choczewo residents opposed to the plans – is more deeply rooted than a simple “not in my backyard” kind of opposition. She feels that nuclear is “an old technology” that can easily be replaced by renewables.

She also points out that the site of the potential nuclear power plant is part of Natura2000, the network of areas protected under EU environmental law.

So why not just bet on renewables?

Given that renewables are cheaper, easier and quicker to build than big nuclear reactors, why invest so much money and time in nuclear? In Śniegocki’s view, there is no need for an “either or” approach.

“There should not be a question of whether to go with renewable energy or to go with nuclear, but rather how much nuclear could be built within some reasonable financial limits and within the schedule,” he says.

Śniegocki thinks that, in order to achieve greater energy independence, Poland should invest in renewables, which are not dependent on imports from other countries and short-term changes in prices on the energy markets (as proven by the recent energy crisis in Europe), but also in nuclear, which will allow Poland “to meet some of the growing demand for electricity, which will increase as we also electrify other sectors [such as] transport and heating.”

Nuclear energy is also a stabilising element in the energy system, providing electricity when sources such as wind and solar are not available, given that no solution has yet emerged on how to cheaply store energy on a large scale.

However, some of Choczewo’s residents are clearly concerned about the fuel supply for the nuclear power plant, as can be seen from the stickers, banners and posters distributed around town.

They worry that the nuclear power plant that – in theory – is supposed to make Poland independent from Moscow will be powered by uranium imported from Russia.

“Polish Atom, Russian Uranium,” read the stickers on the right, seen in Choczewo.

Deputy minister Guibourgé-Czetwertyński tried to assuage these fears, saying that the nuclear fuel in the first years of the plant’s operation will be supplied by the companies providing the technology, and none of them imports fuel from Russia.

Both he and Śniegocki point out that nuclear fuel can be transported and stored more easily than, for example, coal, making it easier to stockpile for years.

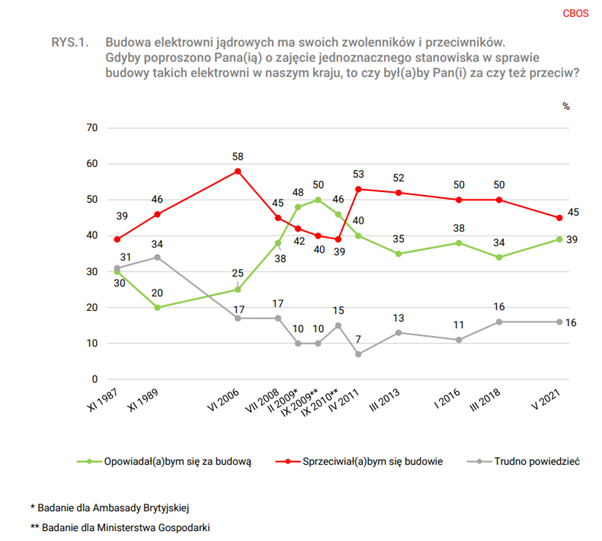

Another concern is safety. Many Poles still have memories of the Chernobyl disaster in neighbouring Ukraine, while the Fukushima disaster of 2011 in Japan turned many against nuclear. Regular polling published by research agency state pollster CBOS found that by 2010, half the public were in favour of building nuclear power plants, with 40% opposed. But support subsequently plummeted, and last year 45% were against and only 39% in favour.

The German question

The Fukushima disaster also turned neighbouring Germany against atomic energy. Berlin has been phasing out nuclear power over the last decade, just as Poland prepares to bring it in.

Earlier this year, a Polish left-wing party, Together (Razem), even suggested that Poland could lease Germany’s unwanted plants. However, on a visit to Warsaw in February, Germany’s environment minister, Steffi Lemke, appeared unfavourable towards Poland’s plans, warning that nuclear is “neither good nor safe” and that “if reactors are built in Poland we will [use] appropriate legal instruments at the European level”.

However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, just days after her visit, has transformed the situation, with many in Germany – including some in its coalition government – calling for the shutdown of some nuclear reactors to be delayed.

Some believe that, with the EU cutting its imports of Russian energy resources, and with the closure of the Nord Stream gas pipelines, Germany will come to regret its decision to abandon nuclear.

Poland, by contrast, which has long been seeking to reduce its reliance on Russian energy, may find its nuclear plans even more beneficial in the new reality – assuming, of course, it can push them through against public scepticism and local opposition.

All images by author.

Alicja Ptak is deputy editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland and a multimedia journalist. She has written for Clean Energy Wire and The Times, and she hosts her own podcast, The Warsaw Wire, on Poland’s economy and energy sector. She previously worked for Reuters.