Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Daniel Tilles

With growing military, economic and energy ties around the Baltic Sea, Poland’s geopolitical focus is increasingly towards the north, unlike for most of its recent history.

“The Baltic must once again become a white-and-red sea,” declared Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk in a speech in the port city of Gdynia last weekend. “The whole of Poland is looking at our sea, the Baltic, with extraordinary focus. Here, once again, our history is unfolding, and our future is unfolding.”

While there was plenty of hyperbole in his declared desire to reassert Polish dominance over the Baltic, his remarks reflect a growing new geopolitical reality. As The Economist remarked earlier this year, “Poland is becoming less central European and more Baltic”.

💬 Premier @DonaldTusk 👇

Cała Polska, w tym mój rząd, z niezwykłym skupieniem patrzy dziś na nasze morze – na Bałtyk. Tutaj po raz kolejny w dziejach rozgrywa się nasza historia i tutaj rozgrywa się nasza przyszłość, która w dużym stopniu będzie zależała od was. pic.twitter.com/HqUsacWll1

— Kancelaria Premiera (@PremierRP) October 4, 2025

Poland was once strongly oriented towards the Baltic, as Tusk – a historian by education from Gdynia’s neighbouring city of Gdańsk – alluded to in his remarks.

At its greatest extent in the 17th century, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s coastline stretched around 1,000 kilometres from near Lębork in the west to what is now Pärnu in Estonia in the east.

But for much of its subsequent history, Poland found itself cut off from the Baltic, with its political, military and economic ties leading east, west and south, rather than north.

From 1793 to 1918, Poland did not exist at all, instead being partitioned between imperial powers based in Saint Petersburg, Berlin and Vienna. In the interwar period, access to the Baltic was limited to the narrow “Polish corridor”, cutting through German Prussia, giving Poland only around 70 kilometres of coastline.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth at its greatest extent in 1619 (source: Mathiasrex/Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY 3.0)

Following World War Two, the redrawn Polish borders now included a greater presence on the Baltic, with around 500km of coastline. However, for decades, the country remained under Moscow’s sway, locked into the Soviet Bloc that stretched to the east and south.

After shaking off communism in 1989, Poland’s most important partners became Berlin, Brussels and, even further to the west, Washington. Meanwhile, tentative efforts were also made to establish regional cooperation with fellow central and eastern European countries through initiatives like the Visegrad Group.

But recent years have seen a growing shift, as Poland builds closer military, energy and economic ties through the Baltic, and rapidly expands its own infrastructure linked to the sea.

Since opening a decade ago, a terminal in the port of Świnojuście has been receiving growing amounts of liquefied natural gas (LNG) transported by sea. In 2022, the Baltic Pipe, bringing Norwegian gas to Poland across the Baltic and through Denmark, opened.

Last year, gas supplied by those two routes covered around two thirds of Poland’s total demand. Construction of a second LNG terminal, which will be located in the Bay of Gdańsk, recently began.

The Baltic Pipe, an idea first conceived in 1991, has finally begun pumping gas from Norway to Poland via Denmark.

The pipeline will bolster both Poland's security and Europe's efforts to wean itself off Russian gas, writes @wjakobik https://t.co/VEnKo14e8Q

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 5, 2022

Poland is also currently constructing its first offshore wind farms in the Baltic – one of them being built with Danish firm Ørsted, another with Norway’s Equinor. Once completed, they are expected to have a capacity of 3.4 GW, which would meet around 16% of Poland’s current electricity demand.

Meanwhile, the country is pushing ahead with its first nuclear power plant, which will be located on its northern coast, cooled by the waters of the Baltic Sea, and will provide a further 3.7GW of capacity.

The combination of nuclear and renewables is intended to help gradually phase out the use of coal, Poland’s traditional power source, mined largely in the country’s south.

Last year, after ending oil imports from Russia’s Druzhba pipeline in 2023, Poland brought in 100% of its oil by sea for the first time. A decade earlier, in 2014, only 25% of oil came by sea and 75% through Druzhba, notes Andrzej Brzózka, head of Polish oil importer Naftoport.

Poland's biggest private energy firm, Polenergia, and Norway's Equinor have approved final investment decisions for the construction of two offshore wind farms in the Baltic Sea.

Their capacity is expected to generate enough power for 2 million householdshttps://t.co/5Z6qi3UK6g

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 20, 2025

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also prompted Finland and Sweden – with strong support from Poland – to join NATO, meaning that, other than Russia, the Baltic is now entirely surrounded by members of the Western military alliance.

Poland has since taken the lead in pushing for joint NATO patrols in the Baltic, while also holding its first-ever bilateral military drills with Sweden there. Last year, Warsaw and Stockholm signed a strategic partnership to enhance military and economic ties.

This year, Poland penned a defence cooperation agreement with Norway and, earlier this month, Norway opened a new training camp for Ukrainian soldiers in Poland as part of an initiative supported by the Baltic and Nordic countries.

Poland and Sweden have launched their first bilateral military exercises, with the aim of “sending a clear signal of deterrence and readiness for joint defence” of the Baltic Sea https://t.co/Aks2C5JZvs

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) September 22, 2025

When Poland recently announced that it was withdrawing from the Ottawa Convention against the use of landmines, it did so jointly with Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia.

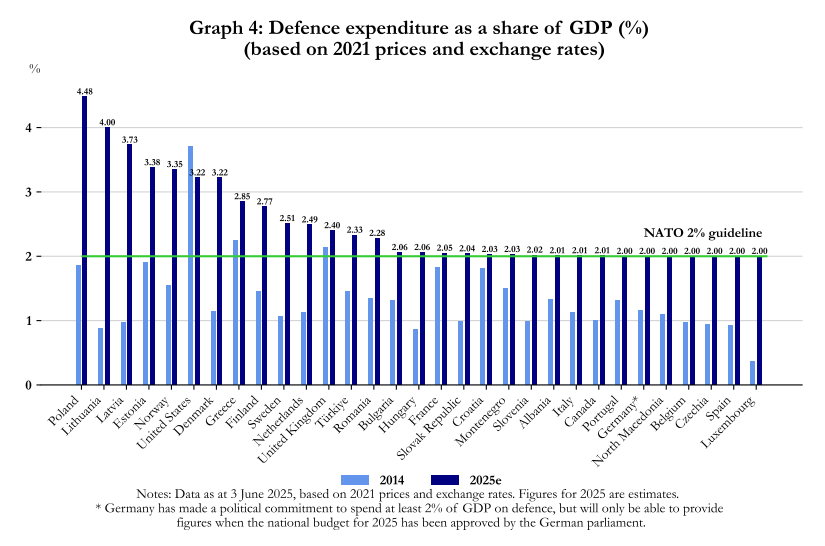

Poland and its Baltic partners have a particularly acute sense of the Russian threat, based on proximity and history. NATO’s five biggest defence spenders this year, as a proportion of national GDP, are Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Norway. Denmark, Finland and Sweden are also in the top ten.

It should be noted, however, that, in Poland’s case, its unprecedented military spending spree in recent years has been focused far more on enhancing its land and air forces than on bolstering its naval power in the Baltic.

The Baltic is also an increasingly important trade route for Poland. During his recent visit to Gdynia, Tusk celebrated the fact that Poland is “becoming – and there is no exaggeration here – a port powerhouse on our sea”.

Gdańsk recently became the EU’s fifth-busiest port, overtaking Algeciras in Spain and HAROPA in France, and behind only Amsterdam, Hamburg, Antwerp-Bruges and Rotterdam.

Meanwhile, Poland is by 2029 scheduled to build a new deepwater terminal in Świnoujście, which the government says will “significantly increase our competitiveness in the Baltic Sea”.

Gdańsk in Poland has become the EU’s fifth-busiest port, overtaking Algeciras in Spain and HAROPA in France, the latest @EU_Eurostat data show.

Meanwhile, national data show that Poland’s ports reported record financial and operational results in 2024 https://t.co/q4QFf8df2G

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) January 15, 2025

This refocus towards the north has come as some of Poland’s other geopolitical relationships fray. To the south, the Visegrad Group – made up of Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic, as well as Poland – is now effectively moribund.

Poland’s former national-conservative Law and Justice (PiS) government had placed great stock in the body, seeing it as a counterweight to western EU powers.

But stark differences over the war in Ukraine – with first Hungary and then Slovakia taking a line much more hostile to Kyiv and sympathetic to Moscow than that of Poland – have torn the V4, as it is known, apart.

The victory of Andrej Babiš, a populist ally of Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, in the recent Czech elections makes it even more unlikely that Poland, under the current Tusk government at least, will take any interest in the V4.

Divisions over Ukraine and Russia were clear as the Visegrad Four met today.

Poland and the Czech Republic called for continued military aid for Kyiv. But Hungary and Slovakia warned that this would extend the war and argued instead for peace talks https://t.co/tZ8eZwwEUw

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 27, 2024

Meanwhile, even to the west, relations with Germany, which were often hostile when PiS was in power, remain tepid under Tusk, who has pushed back against German-backed EU policies on issues such as migration, climate and trade.

Earlier this year, the Polish government reintroduced border controls with Germany in response to Berlin sending illegal immigrants back to Poland. This week, Tusk said he opposed the extradition of a Ukrainian man wanted by Germany on suspicion of sabotaging Russia’s Nord Stream pipelines that run beneath the Baltic Sea.

“The problem with Nord Stream is not that it was blown up. The problem is that it was built,” declared Tusk, in another signal of how Poland has increasingly asserted its interests in the Baltic. The former PiS government was even more vociferous in its condemnation of Nord Stream.

Indeed, Poland’s recent northward realignment appears to be a relatively rare point of agreement between Tusk’s camp and PiS, both of which have deepened Baltic ties during their recent terms in office.

It appears likely, therefore, that Poland’s shifting geopolitical priorities are here to stay.

Polish PM @donaldtusk says it is "not in the interest of Poland or of decency and justice" to extradite to Germany the Ukrainian man recently detained on a European Arrest Warrant for his alleged involvement in sabotage of the Nord Stream gas pipelines https://t.co/W2Yfm4CcCn

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 8, 2025

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Additional reporting by Alicja Ptak

Main image credit: Port of Gdańsk (press materials)

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.