The world’s first pregnant Egyptian mummy has been discovered in Warsaw by a team of Polish scientists using radiological scanning.

The mummy, which dates back to the 1st century BC, was transported to Poland in the early 1800s, and is currently in the collection of the National Museum in Warsaw.

Recent testing by researchers working on the Warsaw Mummy Project found that the embalmed woman was around 28 weeks pregnant when she died. According to a paper published by the team in the Journal of Archaeological Science, the discovery will open up “new possibilities of researching pregnancy in ancient times”.

The 2,000-year-old mummy was initially identified as the body of the male priest and scribe Hor-Djehuti, after hieroglyphic inscriptions on the sarcophagus were translated in the 1920s.

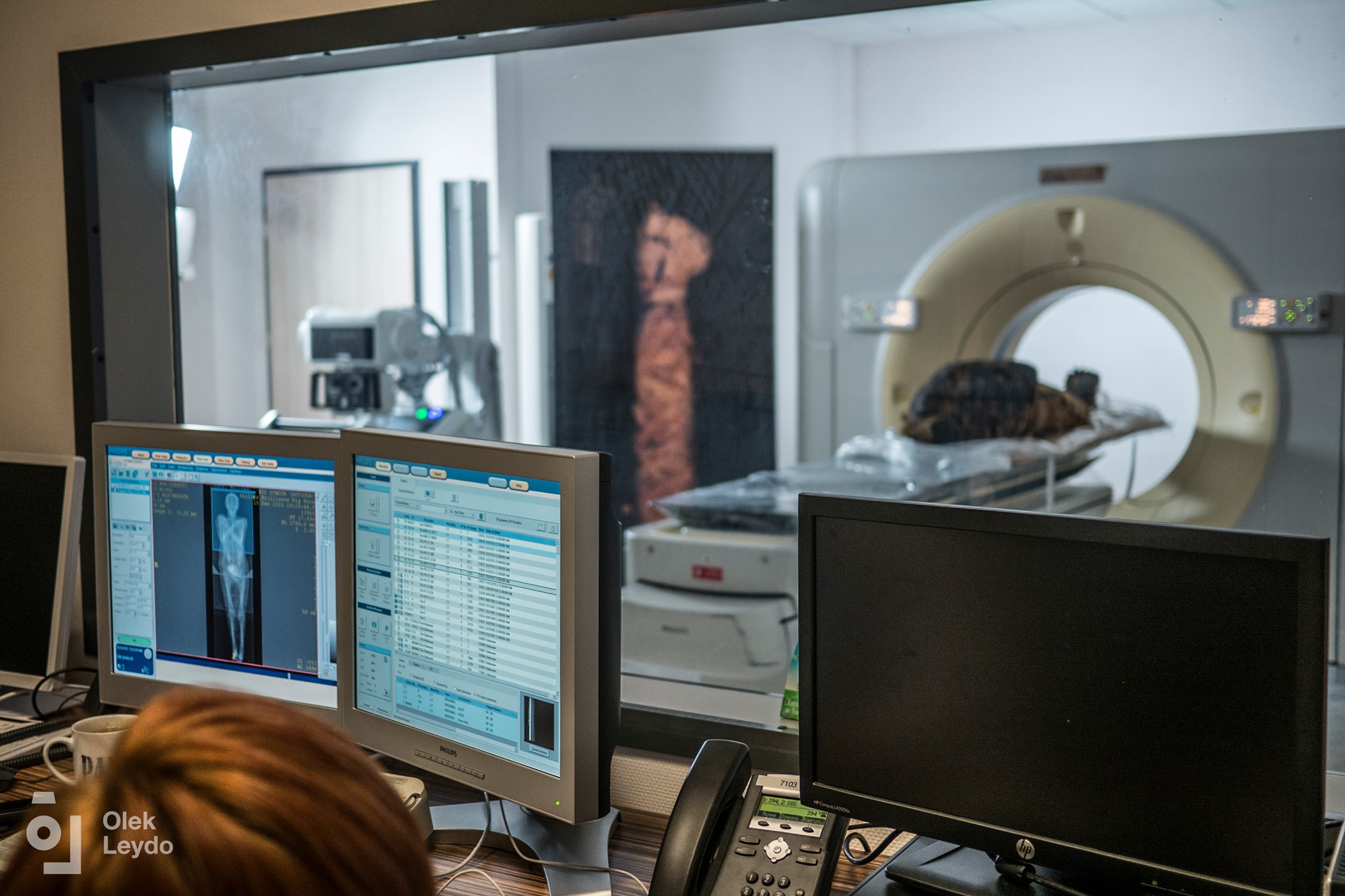

However, non-invasive tomographic scans of the mummy in 2015 – which revealed that it did not have a penis, an organ the Egyptians usually mummified – suggested the body was in fact that of a woman.

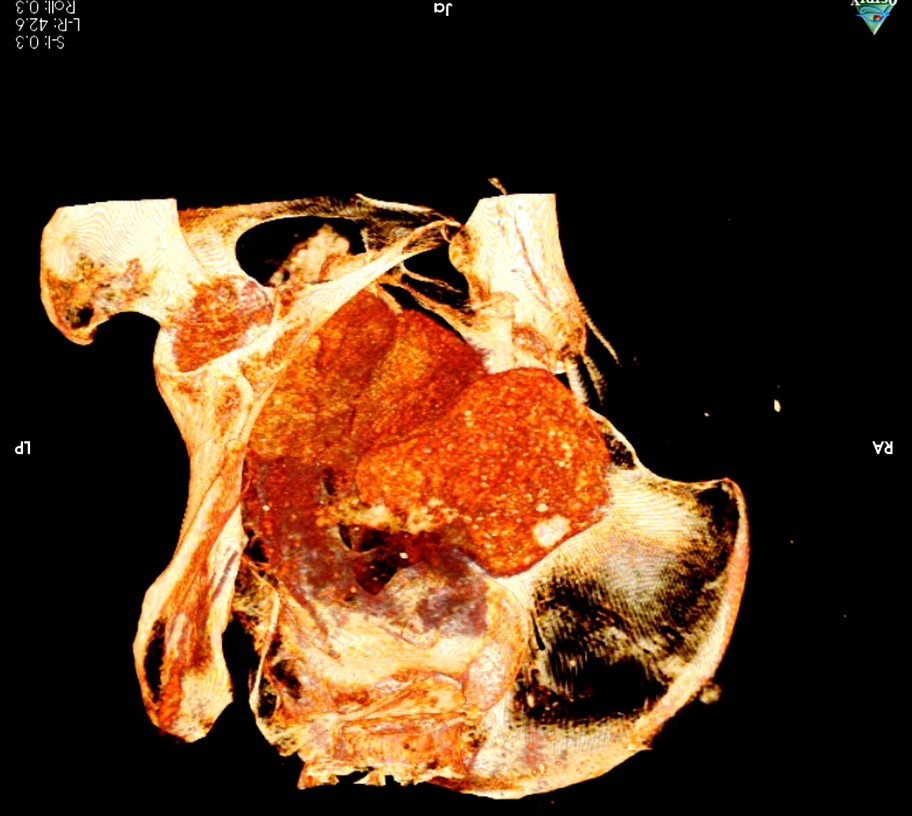

A 3D model also showed long, curly hair flowing to the shoulders, mummified breasts, and female genitalia. The scans then revealed the presence of a foetus in the womb of the mummy.

“We were about to summarise the project and submit the publication to print,” explained Marzena Ożarek-Szilke, an anthropologist and archaeologist at the University of Warsaw, quoted by Onet.

“For the final time, my husband Stanisław, an Egyptian archaeologist, looked at the X-ray images and we saw in the deceased woman’s belly a sight familiar to the parents of three children – a little foot,” she added.

From the size of the foetus, the scientists were able to conclude that the woman was in the 26th-28th week of pregnancy when she died.

“For unknown reasons, the foetus was not removed from the abdomen of the deceased during mummification,” said Wojciech Ejsmond from the Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures of the Polish Academy of Sciences. “Our mummy is the only one so far recognised in the world with a foetus in the womb.”

The sex of the foetus is unknown, and the poor state of preservation of its skeleton meant further measurements could not be taken.

It is also uncertain why the foetus was left in the womb when the mummy was embalmed, although scientists believe this may have been due to difficulties in removing it from the body.

According to the paper published by the team, the discovery “sheds a light on an unresearched aspect of ancient Egyptian burial customs and interpretations of pregnancy in the context of ancient Egyptian religion.”

The team now plan to analyse tissues, which contain traces of blood, to discover how the woman died. They estimate that she was between 20 and 30 years old.

“It is no secret that the death rate, also during pregnancy and childbirth, was high at that time,” said Ejsmond, quoted by Onet. “We believe that the pregnancy could have somehow contributed to the death of the young woman.”

The mummy was acquired in Egypt by a Jan Wężyk-Rudzki, who claimed that it came from “royal tombs in Thebes”. It was donated to the University of Warsaw in December 1826, possibly as a result of the work of Count Stanisław Kostka Potocki, who actively supported the creation of an antiquities collection. It has been in the National Museum collections since 1917.

The Warsaw Mummy Project was established in 2015. It aims to conduct comprehensive analysis of all human and animal mummies at the National Museum.

All images: Warsaw Mummy Project/Facebook

Juliette Bretan is a freelance journalist covering Polish and Eastern European current affairs and culture. Her work has featured on the BBC World Service, and in CityMetric, The Independent, Ozy, New Eastern Europe and Culture.pl.