Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Daniel Tilles

Poles will go to the polls next month to choose their president for the next five years. We have put together a guide explaining everything you need to know about the election: how it works (and if and how you can vote); who is standing (and who is most likely to win); what the campaign has looked like so far; and what impact the outcome may have on Poland.

When is the election happening?

The first round of voting will take place on Sunday 18 May 2025, between 7 a.m. and 9 p.m. If any candidate wins more than 50% of the vote, the elections are over and they will become the next president, serving until 2030.

If, as seems likely, no candidate wins more than 50%, a second-round run-off vote between the top two candidates will take place two weeks later, on Sunday 1 June 2025, with the winner becoming president.

How does the election work?

Unlike parliamentary, European and local elections, which can involve voting for candidates from various lists and with complicated electoral mathematics to confirm the outcome, presidential elections in Poland are very simple.

Polish citizens in both Poland itself and abroad are each able to cast one vote in each round of the election for a single candidate, whom they pick from a single list of all registered candidates.

The votes for each candidate are added up to see who has won (or who the top two are in the first round if no one has won more than 50% of the vote).

How can I vote?

Anyone who is a Polish citizen and has not been stripped of their right to vote for legal reasons can take part in the election.

If you live in Poland, you can find information on voter registration here, and if you wish to vote outside your area of residence in Poland, see here. Information on voting for disabled people and people aged 60+ can be found here.

If you live outside Poland, you can register to vote until 13 May. For further information on the process, see here, here, and here. You can also contact Polish consular services in your country of residence for more information.

W wyborach Prezydenta RP chcesz zagłosować za granicą?

Twój plan działania:

🌐 Wejdź na eWybory

🔎 Odszukaj obwód, w którym chcesz zagłosować

📝 Zapisz się do spisu wyborców

🪪 Weź ze sobą ważny polski paszport (lub w państwach UE – ważny dowód osobisty)

🗳️ Zagłosuj w wyborach— Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych RP 🇵🇱 (@MSZ_RP) April 17, 2025

What is “election silence”?

Under Polish law, any kind of political agitation is banned for the entire day before the election and on election day itself until the close of voting at 9 p.m, with the authorities able to issue fines against those who break the “silence”.

That means not only candidates and political parties themselves, but also the media and members of the public are banned from any kind of activity promoting candidates or otherwise expressing support for them. This applies not only to “real world” activity but also online (though pre-existing forms of support, such as social media posts and election posters, can remain up).

During that period, it is also not permitted to publish opinion polls relating to the election (with fines for doing so ranging from 500,000 to 1 million zloty).

When will we know the results?

As soon as voting closes at 9 p.m. on election day, an exit poll will be released by Ipsos, a leading research agency, based on surveys of voters carried out at 500 randomly selected polling stations.

The exit poll is, of course, not the same as the official result, but in Polish elections it usually offers a pretty accurate indication of the outcome of the vote. The official result will then probably follow within a day or two.

In the first round of the 2020 presidential election, which took place on Sunday 28 June, the final result was confirmed on the morning of Tuesday 30 June. After the second round, which took place on Sunday 12 July, the official result was announced on the evening of Monday 13 July.

This is a final appeal for our emergency campaign to save Notes from Poland.

Next week, we may lose the major grant that sustains our work.

If you value the service we provide, please click below and make a donation to help it continue https://t.co/0gVkMlaA0W

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) April 22, 2025

Why does the election matter?

In Poland, presidents are not generally involved in the day-to-day governance of the country. Although they have the power to initiate legislation, this is rarely used. While technically the president is head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces, they usually play a figurehead role in foreign and defence policy rather than setting the agenda.

However, the president wields one extremely powerful tool: the right to veto bills passed by parliament, an action that can only be overturned by a three-fifths majority of MPs. Given that the current ruling coalition does not possess such a majority, it cannot introduce laws unless the president approves them.

That has been a major obstacle for the current government – which came to power in December 2023 – because the current president, Andrzej Duda, is aligned with the opposition Law and Justice (PiS) party. That has led him to veto a number of bills and send others to the constitutional court for assessment (effectively killing them off, given that the court is stacked with PiS-nominated judges).

President Duda has vetoed a law that would have made Silesian a recognised regional language in Poland.

He argued that Silesian is a dialect of Polish, rather than a language in itself, and also cited national security concerns https://t.co/QpFfVXnaes

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 29, 2024

The government will only be able to proceed with key parts of its agenda – judicial reforms, liberalising the abortion law (though this is an area the ruling coalition is struggling to agree on itself), strengthening LGBT+ rights – if a more friendly president is elected to replace Duda, whose second and final term ends this August.

Given that the president will have a five-year term, a large part of their time in office will also cover the period after the next parliamentary elections in 2027, when the shape of the next government will be decided.

That means that the result of this year’s election is likely to influence both the outcome of the 2027 vote and the ability of whatever government is subsequently formed to pursue its agenda.

Who are the candidates?

In total, 13 candidates met the requirements to stand (the joint-highest ever number). They are (in alphabetical order of surname, with links to their campaign websites):

- Bartoszewicz, Artur

- Biejat, Magdalena

- Braun, Grzegorz

- Hołownia, Szymon

- Jakubiak, Marek

- Maciak, Maciej

- Mentzen, Sławomir

- Nawrocki, Karol

- Senyszyn, Joanna

- Stanowski, Krzysztof

- Trzaskowski, Rafał

- Woch, Marek

- Zandberg, Adrian

Who are the frontrunners?

The current favourite for the presidency is Rafał Trzaskowski, the candidate of Poland’s main ruling party, the centrist Civic Platform (PO), who has topped every single opinion poll since the campaign began. Trzaskowski is the mayor of Warsaw and was the runner-up in the 2020 presidential election, narrowly losing to Duda in the second-round run-off.

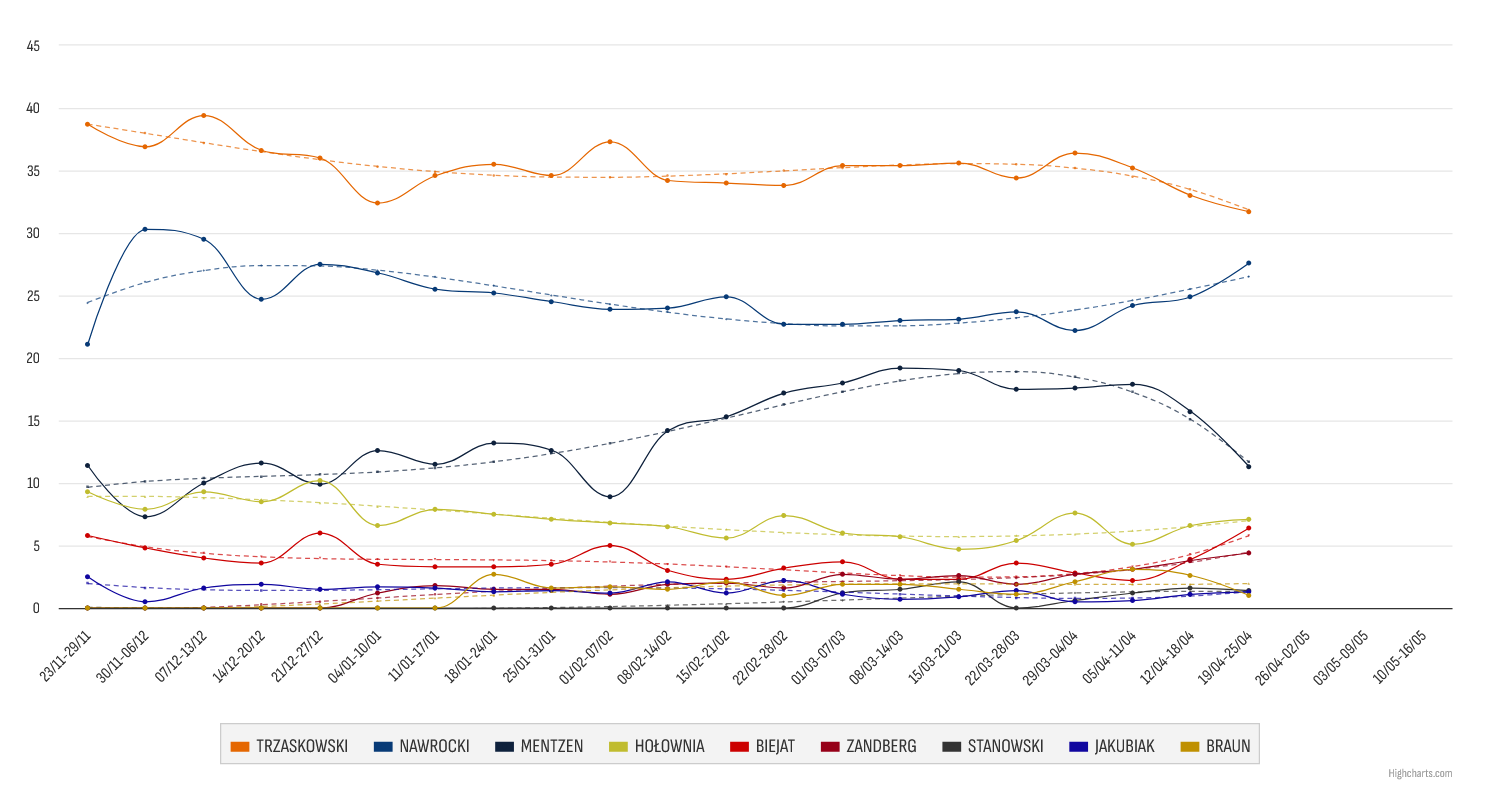

This time around, Trzaskowski has consistently been polling 30-40% throughout the campaign, well ahead of his rivals. Polling also suggests he would win the second around against either of his two main challengers.

One of them is Karol Nawrocki, technically an independent but supported by the national-conservative PiS. Throughout the campaign, he has consistently been in second place according to poll averages, with support of between 20% and 30%.

Nawrocki, a historian who is president of the state Institute of National Remembrance, has never previously stood for elected office.

Weekly average of support in polls for the leading candidates in Poland’s 2025 presidential election, compiled by ewybory.eu

The dark horse of the campaign has been Sławomir Mentzen, the candidate of the far-right Confederation (Konfederacja), another opposition party. Starting his candidacy with around 10% support last November, he steadily rose to reach an average of almost 20% by March, closing the gap to second-placed Nawrocki to only around 4 percentage points.

However, Mentzen has subsequently slid back down to support of around 16%, suggesting that – as things currently stand – it will be Trzaskowski and Nawrocki who will proceed into the second-round run-off. However, a lot can still happen in the three-and-a-half weeks until polling day.

Among the remaining ten candidates, the only ones currently averaging above 3% in polling are Szymon Hołownia of the centrist Poland 2050 (Polska 2050), who finished third in the 2020 presidential election; Magdalena Biejat of The Left (Lewica); and Adrian Zandberg of the left-wing Together (Razem) party.

What has the campaign focused on?

The overriding theme of the campaign has been the interlinked issues of security and migration.

That has stemmed from the international situation: Russia’s ongoing war in neighbouring Ukraine; the doubts sown over security and alliances by Donald Trump’s return to the White House; and the crisis on Poland’s border with Belarus, where tens of thousands of migrants and refugees – mostly from the Middle East, Asia and Africa – have tried to cross with the assistance and encouragement of Belarus and Russia.

The uncertain geopolitical situation has overshadowed a campaign many thought would be dominated by domestic issues.@AleksSzczerbiak looks at how the war in Ukraine and return of Donald Trump may impact the outcome of Poland's presidential election https://t.co/qr8Jj53CBU

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) April 22, 2025

The main three candidates have all sought to present a tough line on those issues. That was to be expected of the two right-wing figures, Nawrocki and Mentzen, but Trzaskowski was previously regarded as a representative of the more liberal wing of PO. However, his relatively hard stance on immigration and security during the campaign has reflected those of the party and its leader, Prime Minister Donald Tusk, in recent times.

Trzaskowski has called for restricting child benefits for Ukrainians (Poland’s largest immigrant group), declared a “zero tolerance” approach to crime committed by immigrants, and advocated a rise in defence spending to 5% of GDP.

However, he has also reiterated his previous support for overturning PiS-era policies by ending Poland’s near-total abortion ban, restoring prescription-free access to the morning-after pill, and restoring the legitimacy of the constitutional court.

Rafał @Trzaskowski_, the presidential candidate of Poland's main ruling party, says his priority would be to sign bills on access to contraception, recognising Silesian language, and the constitutional court blocked by incumbent President @AndrzejDuda https://t.co/hEEKkmlf9E

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 15, 2025

Nawrocki, meanwhile, has pledged to propose a law ensuring that Poles have priority access ahead of immigrants when it comes to medical treatment and school places. He has also talked tough on Ukraine, saying that he “cannot currently envision the country” joining the EU or NATO and blaming “European elites” for the war there.

The PiS-backed candidate has tried to present the election as a “referendum on Tusk’s government”, accusing PO and Trzaskowski of representing German, rather than Polish, interests and warning that their pro-EU stance could harm relations with the US. He has also declared his opposition to liberalising the abortion law.

Mentzen has offered the most extreme rhetoric on immigrants – who he says Poland should “deport instead of trying to integrate” – and on Ukraine, calling for an “agreement with Putin to end the war”. His campaign has also placed emphasis on Mentzen’s libertarian economic views, with pledges to slash taxes and public spending.

Conservative presidential candidate @NawrockiKn has pledged to submit a bill guaranteeing that “Poles cannot be treated worse in their own country than immigrants”.

He wants Polish citizens to be given priority over immigrants in healthcare and education https://t.co/9514SiM5Xe

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) April 9, 2025

Will there be televised debates?

On 11 April, eight of the 13 official candidates took part in one or both of two hastily arranged, controversial and rather chaotic debates, the first televised by Republika and the second by Polsat, TVN and TVP. A few days later, Republika hosted another debate, which was attended by ten candidates (Trzaskowski being among those who skipped it).

TVP, which is Poland’s state broadcaster, has also invited all candidates to attend a debate on 12 May, six days before the first round of the election. It is possible other broadcasters will still organise their own debates too.

Will the results of the election be accepted?

A major question hanging over the election is whether the result will be accepted by all parties given doubts over the legitimacy of the Supreme Court chamber that is tasked with verifying election results and assessing any legal challenges relating to elections.

The chamber was created as part of PiS’s contested judicial reforms when it was previously in power. All of its judges were appointed through the National Council of the Judiciary (KRS), another body overhauled by PiS in a manner that various Polish and European court rulings have found rendered it (and therefore the judges appointed through it) illegitimate.

The current government does not recognise the legitimacy of that chamber or such judges but has not been able to reform the system due to opposition from President Duda, who last month vetoed a bill that would have changed how election results are validated by the Supreme Court.

The president has vetoed a bill passed by the ruling coalition that would have changed how the Supreme Court validates the results of this year's presidential election.

The speaker of parliament warns there could be "legal chaos" without the measures https://t.co/dKxuadluCE

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 11, 2025

That all raises the question of whether this year’s presidential election results will be regarded as valid by all parties concerned. However, the same Supreme Court chamber also validated the results of the 2023 parliamentary elections that brought the current government to power, as well as last year’s European and local elections.

It would be odd, therefore, if politicians and parties who accepted those results now try to challenge the presidential election outcome based on doubts about the chamber’s legitimacy.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Patryk Ogorzalek / Agencja Wyborcza.pl

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.