Poland has seen the largest decline in rule of law over the last year among all countries in the European Union, according to an international index. The country’s drop was driven in particular by lower scores for constraints on government powers and fundamental rights.

The World Justice Project (WJP), a Washington-based think tank, today publishes its annual Rule-of-Law Index, based on surveys of 4,200 legal experts and more than 138,000 households around the world.

In the WJP’s ranking, Poland has – like in many other such indexes – recorded a consistent downward trend since the national-conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party came to power in 2015 and embarked upon a controversial and contested overhaul of the judiciary, media and other institutions.

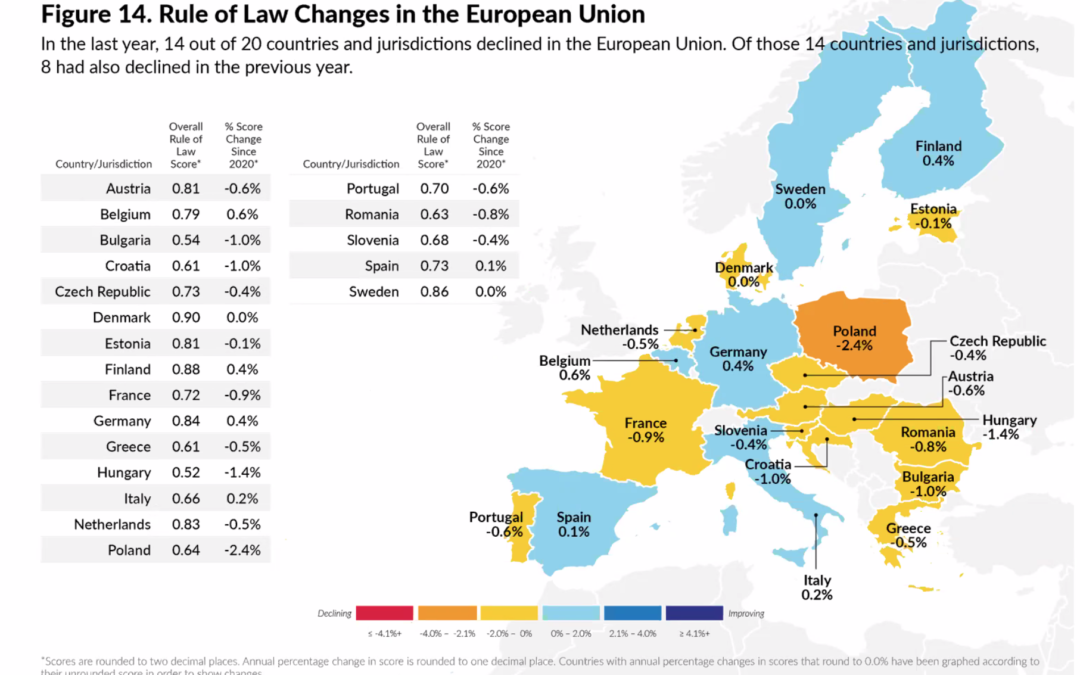

That slide continued this year, with WJP finding that Poland’s rule-of-law score declined by 2.4% to 0.64 (on a scale of 0 to 1). That was a larger relative drop than for any other member state, and means that only five EU countries (Hungary, Bulgaria, Greece, Croatia and Romania) are below Poland.

Source: World Justice Project

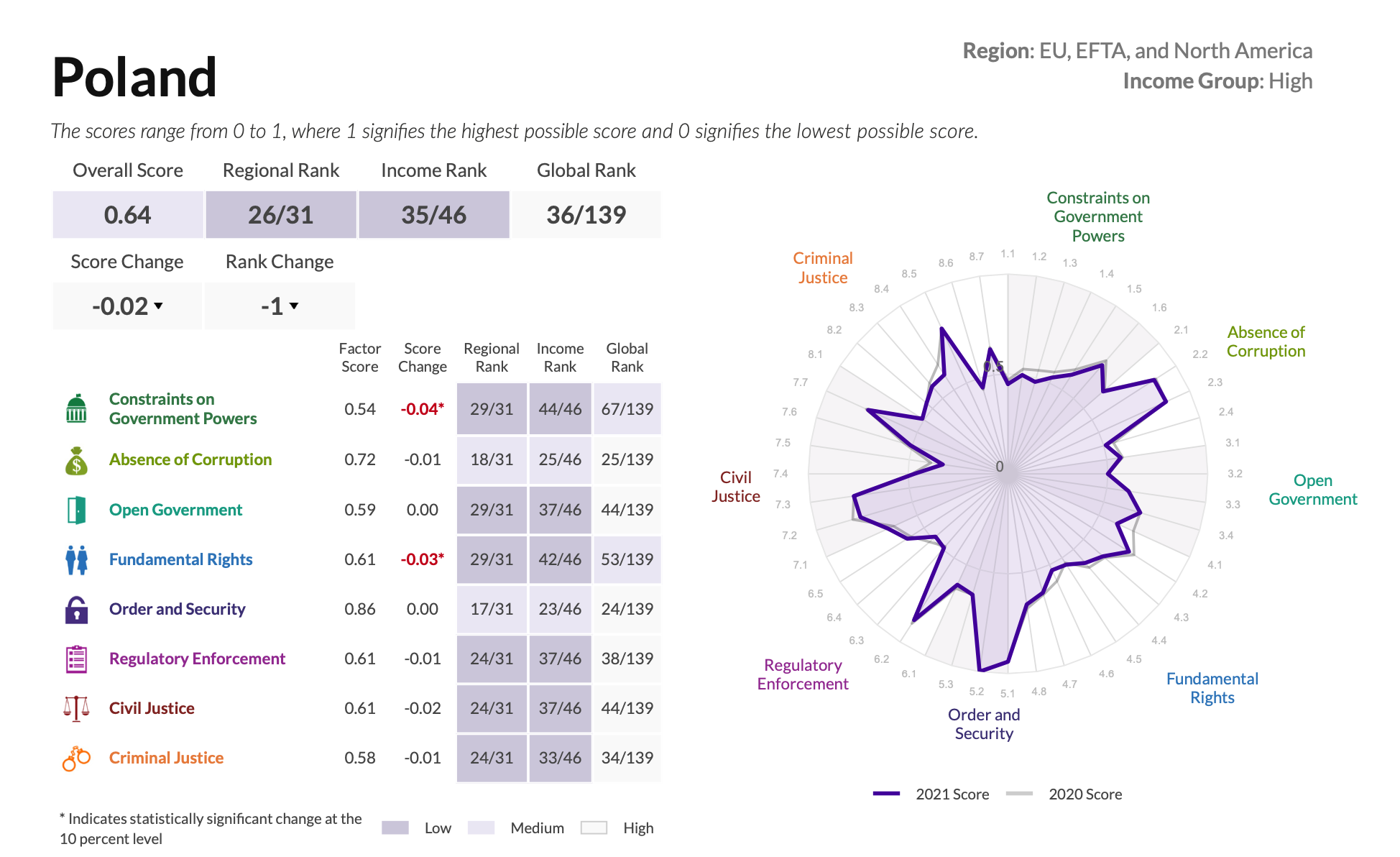

Poland now ranks 26th of 31 countries in the EU, European Free Trade Association and North America region that are included in the index. It is 36th of 139 countries and jurisdictions worldwide. Its rule-of-law score has fallen from 0.71 in 2015, the first year that the index was compiled.

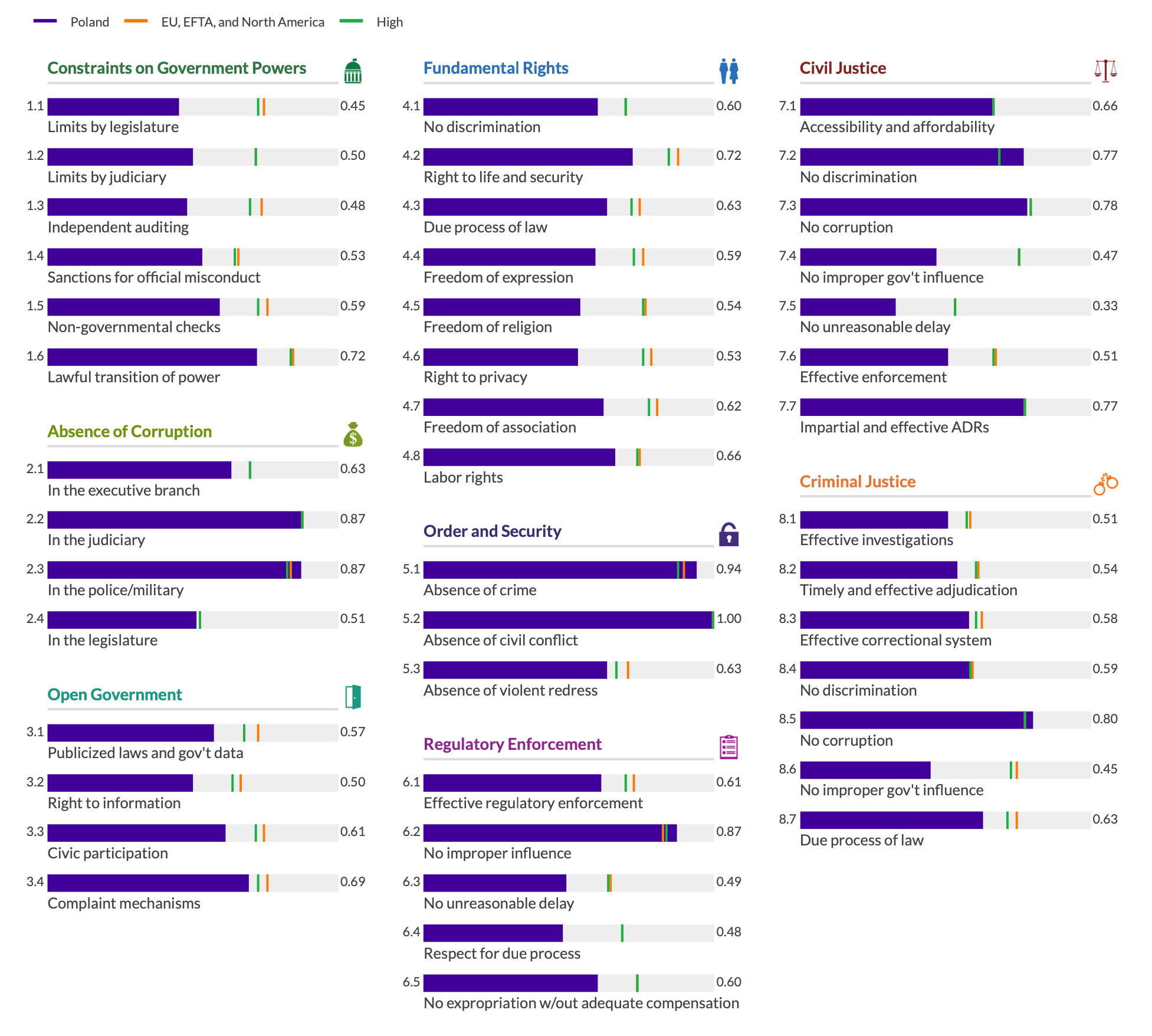

Among the report’s eight key factors, Poland has notably deteriorated in measures of “constraints on government powers” and “fundamental rights”. These two categories are also where Poland ranks lowest relative to other countries, in 67th and 53rd place respectively.

Poland’s does best in terms of “order and security” (24th) and “absence of corruption” (25th).

Source: World Justice Project

This year’s Rule-of-Law Index finds that 84.7% of people live in countries that experienced declines in democratic standards amid the pandemic. “This…should be a wake-up call for us all,” said WJP’s head Bill Neukom in a press release shared with Notes from Poland.

The top three performers in the ranking – both in Europe and the world – were Denmark, Norway, and Finland. The worst three countries globally were Democratic Republic of the Congo, Cambodia, and Venezuela, while the biggest declines were recorded by Belarus (-7.5%) and Myanmar (-6.3%).

Poland has also recently slumped in a number of other similar rankings. In the Human Freedom Index, published by libertarian think tank the Cato Institute, Poland now ranks 45th overall worldwide – behind Albania, Cabo Verde and The Bahamas – slipping from a high of 21st in 2011.

Another US-based NGO, Freedom House, reported earlier this year that Poland has recorded the largest decline in democracy of any country in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Last year, the same organisation found that Poland can no longer be classified as a full democracy.

Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem), which produces the largest global dataset on democracy, recently found that Poland has moved further towards autocracy than any other country in the world over the last decade.

In the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index, Poland has since 2016 been categorised as a “flawed democracy”. Its score has fallen from 7.09 (out of 10) in 2015 to 6.85 in 2020 (though that last year did see a rise from an all-time low of 6.62 in 2019).

Under PiS, Poland has also declined from its highest ever position of 18th in the World Press Freedom Index compiled annually by Reporters Without Borders to its lowest ever ranking of 64th this year.

One exception has been the Index of Economic Freedom compiled by the Heritage Foundation, a conservative US think tank, in which Poland has risen from a score of 68.6 (out of 100) in 2015 to 69.7 in 2021.

Poland’s government has argued that the country’s declining position in most rankings of democracy – as well as regular criticism from international institutions – result from outsiders failing to properly understand the situation, being misled by the Polish opposition, or simply being biased.

PiS argues that it has actually improved Polish democracy by rebalancing a media landscape that was previously dominated by liberal-leaning outlets and by removing “post-communists” from the judiciary. However, critics note that PiS itself has appointed former communists to the courts.

Rule-of-law issues have regularly put Poland at loggerheads with the EU. The European justice commissioner, Didier Reynders, recently warned that “decisive action” may be taken against Poland given the government’s failure to address problems regarding the rule of law.

In response to such concerns, the Polish government has accused Brussels of holding a “colonial” attitude towards Poland and of applying different standards to eastern member states than to western ones.

Main image credit: World Justice Project

Maria Wilczek is deputy editor of Notes from Poland. She is a regular writer for The Times, The Economist and Al Jazeera English, and has also featured in Foreign Policy, Politico Europe, The Spectator and Gazeta Wyborcza.