By Filip Mazurczak

Before the first partitions of the 18th century, Poland was, with some significant exceptions, a remarkable experiment in religious tolerance.

“I am not the king of your consciences,” King Sigismund II Augustus said, while the great Renaissance humanist bishop Erasmus of Rotterdam frequently wrote with admiration: “Polonia mea est” (“Poland is mine”).

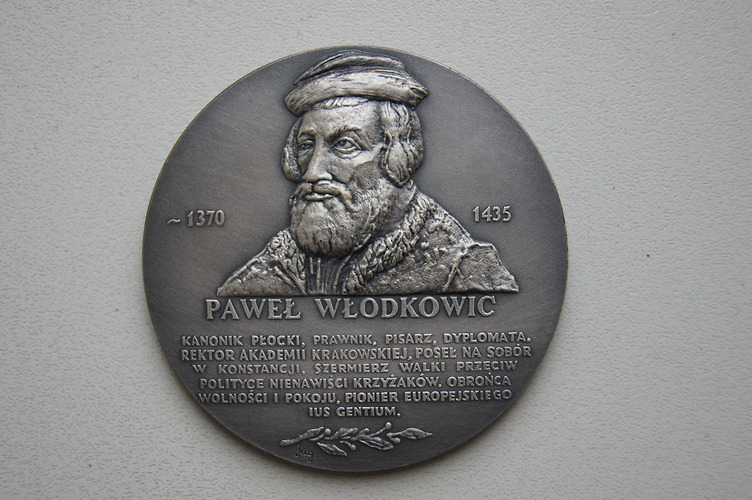

Perhaps the greatest mind of this legacy of tolerance was Paweł Włodkowic, a 15th-century scholar and clergyman who made some of the world’s earliest arguments in favour of international human rights, which were influential both at the time and over the following centuries. At a time when non-Christians faced violence and persecution in Europe, he called for tolerance towards pagans, Jews and Muslims.

Yet, while many of the later thinkers that he influenced remain well known, Włodkowic is little remembered even in his native Poland, and almost completely forgotten outside it. His ideas and legacy are worth understanding and commemorating.

Spreading the gospels with the sword

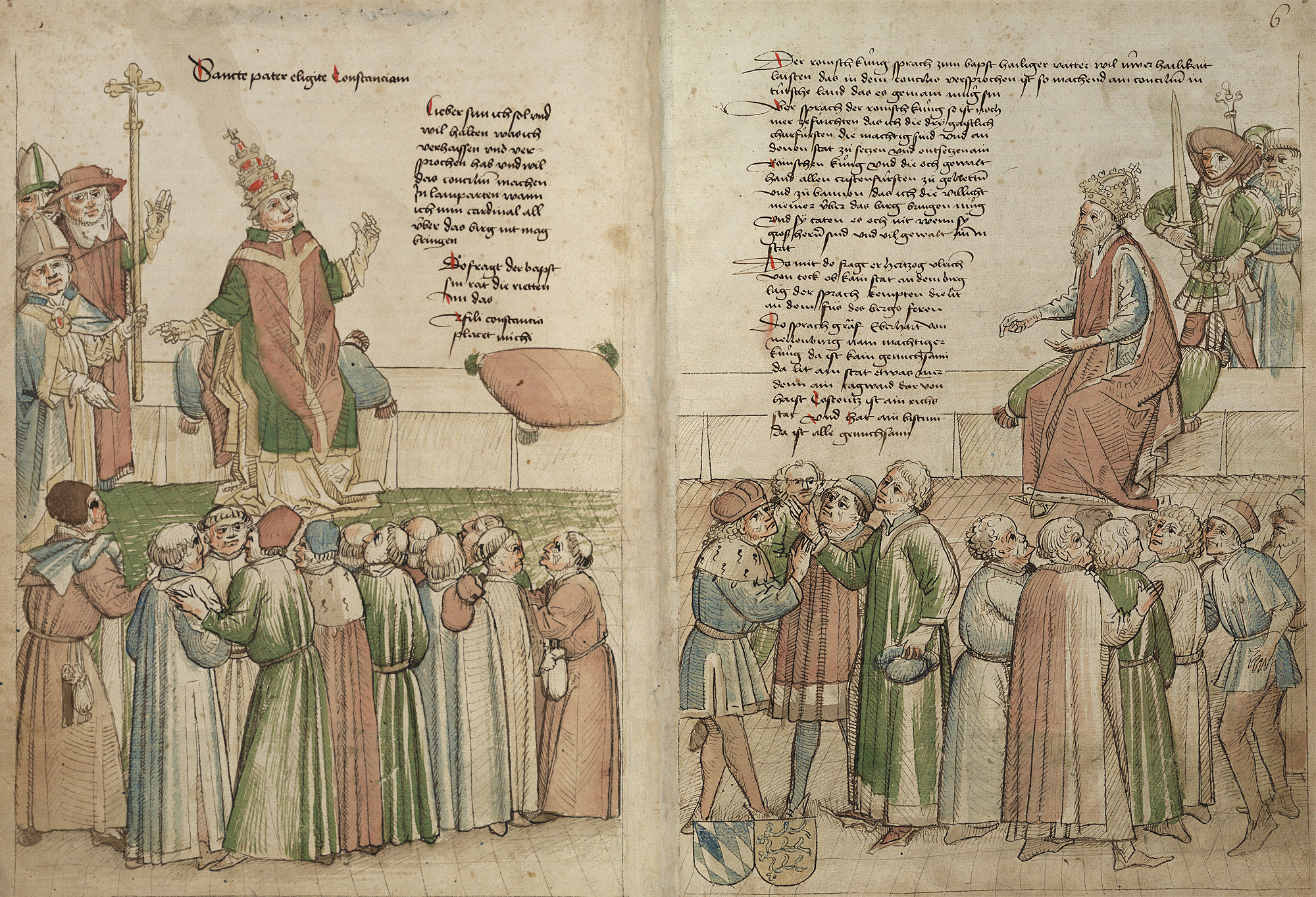

The Council of Constance of 1414 was, until the 20th century, the largest ever international summit of world leaders. Although the Polish delegation was headed by Archbishop Mikołaj Trąba, the first primate of Poland, it was Włodkowic who made the greatest impact.

The main aim of the council, summoned by Antipope John XXIII, was to end the Western Schism, which resulted in at first two, and later three men claiming to be pope.

Council of Constance, 1414-18 (illustration from chronicle of Ulrich von Richenthal; image in public domain)

It also dealt with two precursors of the Protestant Reformation, Jan Hus and John Wycliffe. The former was sentenced to burning at the stake, while the latter’s writings were condemned as heretical (Wycliffe avoided Hus’s fate because he had died three decades earlier).

Finally, the council aimed to resolve the conflict between Poland and the Teutonic Order, which was founded as an order of hospitaller friar-knights during the Crusades in Acre in 1190 to provide medical assistance to German crusaders.

In 1235, Duke Konrad I of Masovia invited the Teutonic Knights to Poland to protect the country against constant raids. Over time, however, the Teutonic Knights began to plunder Polish lands, treat the Poles brutally, and attempt to violently convert the pagan Lithuanians.

The 13th-century Teutonic castle in Malbork, Poland (Gregy/Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 3.0 PL)

The Teutonic Order’s aggression against Lithuania continued even after it had converted to Christianity through Grand Duke of Lithuania Jogaila (Władysław II Jagiełło) following his marriage to Jadwiga (Hedwig), Queen of Poland.

The prophet of Constance

We know little of Paweł Włodkowic’s early life or even the year of his birth, although historians generally estimate it at about 1370. He was the son of the nobleman Włodzimierz of Brudzyn and was descended from the Dołęgów clan, which Poland’s chronicler Jan Długosz considered to be among the 71 oldest Polish aristocratic families.

Like St Francis of Assisi, Włodkowic came from a wealthy family, but he became a defender of the weak and oppressed. He was educated at Płock cathedral school before deciding to become a priest, continuing his education in Prague and Padua.

In 1409, Włodkowic took part in the Council of Pisa, which unsuccessfully tried to end the Western Schism. Upon returning to Poland, he became a canon of Kraków cathedral and the rector of the Academy of Kraków (now known as the Jagiellonian University). In 1412, he was Poland’s representative during its negotiations with the Teutonic Knights.

The main inspiration for Włodkowic’s doctrine of international human rights was another scholar-priest from Kraków, Stanisław of Skarbimierz (1365-1431). Around 1410, when the Polish-Lithuanian military led by Jagiełło defeated the Teutonic Knights at Grunwald, Stanisław preached a sermon titled De bellis iustis (“On Just Wars”).

In it, he argued that no one can wage war without a warranted reason, such as the defence of one’s fatherland or an attempt at reclaiming one’s stolen property.

According to Stanisław, hatred cannot be the cause for war, and diplomacy should be used first to resolve conflicts. Although he did not explicitly address the conflict between the Teutonic Knights and Poland in his sermon, its context was obvious to his audience.

In his writings at the Council of Constance, Włodkowic most often cited the Ten Commandments, arguing that the Teutonic Knights constantly violated the fifth and seventh commandments (“Thou shalt not kill” and “Thou shalt not steal”).

He called them a heretical sect and denied the right of any military order to exist, referring to St Thomas Aquinas and saying that a religious order can participate in a military conflict only if it is granted exceptional permission from the pope.

During the council, the Teutonic Knights referred to the privileges they had been granted by Popes Alexander IV and Clement IV. Włodkowic replied that the pope lacks the power to give anyone authority to convert using violence. He argued that authority can come from one of three sources: God, the will of the sovereign, or violence. Authority is just only if it comes from the first two sources.

Furthermore, Włodkowic argued that not only the lives, but also the property of pagans should be protected against Christian aggression. He believed that papal privileges that allow for military aggression against anyone, including pagans, are by their nature heretical. Włodkowic wrote:

pagans cannot be afflicted with war without a justified reason, nor can they be invaded, oppressed, or have their state seized. Strictly speaking, one cannot act in this way only in order to spread the Christian faith if there is no other just reason for war. Those who arrive at different conclusions commit an error against the faith.

During the council, Włodkowic, who believed that no one can be coerced into orthodoxy, also defended Jan Hus against burning at the stake. When asked if Jews or Muslims could be expelled, Włodkowic replied that if they were not a threat to Christians, doing so would be sinful. According to Włodkowic’s doctrine, every war of aggression is unacceptable.

His views in this regard were strongly influenced by Pope Innocent IV (1195-1254), who believed that there is a natural law created by God that superseded all anthropogenic legislation, thus making all humans subject to the same laws. Innocent IV used these arguments when prohibiting Catholics from attacking Jews and stealing their property and also issued a bull condemning blood libel charges in 1247.

The oldest mosque in Poland – which serves one of the oldest Muslim communities in Europe – has been renovated with the help of public funds for the conservation of monuments https://t.co/PwWfDsnvma

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 21, 2020

In the late Middle Ages, the dominant view on the rights of pagans came from the doctrine of the Italian Cardinal Enrico de Segusio (1200-1271). This Italian prelate believed that, beginning with Christ’s time, only faithful Christians can possess political authority and thus they have the right to conquer heathens. During the Council of Constance, Włodkowic argued that, although Segusio was popular, his views contradicted Innocent IV’s.

In his speeches, Włodkowic referenced the Ten Commandments, St Augustine, Aquinas, Pope Innocent IV, Roman law, and even pagan thinkers like Cicero. The novelty of his doctrine rested in the synthetic presentation of the ideas of such diverse thinkers into a coherent whole that became a doctrine of the rights of nations.

Meanwhile, Johannes Falkenberg (approx. 1365-1430), a German Dominican, was the advocate of the Teutonic Knights at the council. He gave its participants a pamphlet titled A Satire on the Heresy and Other Villainies of the Poles and Their King Jagiełło.

In this text, he calls the Poles “loathsome heretics” and “shameless dogs” who had never sincerely accepted Christianity and defended the pagans of the Baltic. Falkenberg wrote: “Killing the Poles and their kings is more glorious than killing pagans.”

The Teutonic Knights initially enjoyed the significant support of many western nations. Thanks to the efforts of the Polish delegation, however, the council’s commission of cardinals condemned Falkenberg’s writings, while the Dominican Order deemed him a heretic and sentenced him to life in prison.

The Council of Constance ended the 39-year schism with the election of Martin V as pope. The new bishop of Rome, however, defended the Teutonic Knights and successfully pleaded for Falkenberg’s release from imprisonment. Although the council commission of cardinals condemned the Teutonic Order’s brutality against Poland and Lithuania, the pope implored the Poles to make concessions to the hospitallers.

After defending Polish interests against the Teutonic Knights before the court of Sigismund of Luxembourg, king of Bohemia and a future Holy Roman Emperor, Włodkowic became a parish priest in Kłodawa in Greater Poland in 1424. Towards the end of his life, he returned to Kraków, where he participated in inaugurating Queen Jadwiga of Poland’s cause for sainthood.

A forgotten father of international law

Western historians have long claimed that the notion that all people on earth deserve the same rights irrespective of their religion or international borders can be traced to the School of Salamanca in 16th-century Spain.

Meanwhile, Francisco de Vitoria, the best-known representative of the Salamanca School, is considered to be the father of the concept of the rights of nations. When Spain and Portugal conquered the Americas in the 16th century, this Spanish Dominican friar argued that although the Indians were pagans, they had been created in God’s likeness and therefore they had the same rights as Christians.

The most famous law graduate of Salamanca at this time was Bartolomé de Las Casas, another Spanish Dominican who defended the dignity of the Indians before the pope and emperor and published extensive works documenting his compatriots’ genocidal crimes against the indigenous population of the New World.

It is very likely that de Las Casas and de Vitoria were familiar with Paweł Włodkowic’s treatises, which were widely disseminated across Renaissance Europe, although they did not explicitly refer to him him. Indeed, de Vitoria’s concepts are very similar to Włodkowic’s.

Ludwik Ehrlich, a Polish legal scholar who devoted years of study to Włodkowic, has noted that his views were more progressive than those of his Spanish successors in that de Vitoria allowed for the violent overthrow of a pagan ruler, which Włodkowic had categorically rejected.

In his approach to interreligious dialogue and peace, Pope John Paul II was strongly influenced by Włodkowic long before becoming pope and publicly referenced him twice during his pontificate: during his visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1979 and in the United Nations in 1995. At the former death camp, the pope said:

Where force is stronger than love, Włodkowic writes, one defends one’s own interest, not that of Jesus Christ, which leads to violations of God’s law. The law condemns those who attack those who wish to live in peace; both the natural law, which proclaims: ‘Do unto others what you yourself desire!’ and God’s law, which condemns all forms of plunder with the commandment: ‘Thou shalt not steal!’ and all forms of violence with the commandment: ‘Thou shalt not kill!’

Despite the Polish pope’s indebtedness to Włodkowic, the medieval scholar remains relatively little-known in present-day Poland. There is a private college named after him in Płock, while since 2006 Poland’s ombudsman presents the annual Paweł Włodkowic Award for the defence of human rights.

Plaque in honour of Włodkowic in Płock, describing him as a “Champion of the battle against the Teutonic Knights’ policy of hatred, defender of freedom and peace, and pioneer of the European ius gentium [law of nations]”

At the Jagiellonian University, where Włodkowic was once rector, there is not even a plaque commemorating him. In public debate, Polish scholars, politicians, clergymen, or lawyers seldom quote him.

Paweł Włodkowic’s courageous and innovative defence of the rights of all peoples deserves international recognition. Sadly, his legacy has largely faded into oblivion, and this cannot be remedied until Poles themselves discover and celebrate it.

Main image credit: bishops debating with the pope at the Council of Constance, from Chronicle of Ulrich von Richenthal/Wikimedia Commons (public domain)