Poland has fallen to its lowest ever position of 64th out of 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index compiled annually by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), a Paris-based NGO that seeks to promote and defend independent journalism and access to information.

The latest ranking places Poland two positions lower than last year, continuing a longer-term decline. In 2015, the country reached its highest ever position of 18th. But, after the Law and Justice (PiS) government come to power that year, Poland has recorded a decline in every version of the annual index.

Poland – which received an index score of 28.65 (up by 0.19) – is classified by RSF as “problematic”. It now finds itself directly below Malawi (62nd) and Armenia (63rd) and above Bhutan (65th) and Côte d’Ivoire (66th).

Norway, Finland, Sweden and Denmark yet again take the top positions. Germany falls two places to 13th, while the Czech Republic is ranked 40th and Slovakia 35th. Hungary and Ukraine follow far behind in 92nd and 97th respectively, while Belarus is 158th.

#RSFIndex: RSF unveils its 2020 World Press Freedom Index:

1: Norway 🇳🇴

2: Finland 🇫🇮

3: Sweden 🇸🇪

13: Germany 🇩🇪

33: United Kingdom 🇬🇧

34: France 🇫🇷

41: Italy🇮🇹

44: United States 🇺🇸

67: Japan 🇯🇵

111: Brazil 🇧🇷

142: India 🇮🇳

146: Algeria 🇩🇿

180: Eritrea 🇪🇷https://t.co/DplP3IsTsu pic.twitter.com/a31BxusUwu— RSF (@RSF_inter) April 20, 2021

Reporters Without Borders notes that Europe has seen its leadership in media freedom challenged by the rise of illiberal democracies. Its country report for Poland highlights efforts to curb media plurality, the bias of state media, and a recent “black screen protest” by private media.

“The [Polish] government is pursuing its ‘repolonisation’ of the privately owned media with the declared goal of influencing their editorial policies or, in other words, censoring them,” claim the authors, who noted state oil giant Orlen’s purchase of hundreds of local newspapers and websites.

PiS has an openly declared goal of bringing foreign-owned media in Poland into Polish hands, including through buyouts by state-owned media. However, it argues that this is a policy in the national interest rather than for its own political benefit, and denies an aim of censorship.

RSF also noted the biased coverage of last year’s presidential election by state media. Public broadcasters openly “backed President Andrzej Duda’s successful campaign for re-election” while at the same time “doing their best to discredit his main rival”.

During the campaign, news broadcasts on public television regularly promoted Duda while attacking Rafał Trzaskowski, the main opposition candidate. Trzaskowski was accused of working on behalf of a “powerful foreign lobby” linked to George Soros and of seeking to “fulfil Jewish demands”.

Last year, election observers from the OSCE reported that the “campaign was characterised by intolerant rhetoric and a public broadcaster that failed in its duty to offer balanced and impartial coverage”. Poland’s commissioner for human rights, Adam Bodnar, also accused state media of violating their statutory impartiality.

RSF’s report on Poland also mentions alleged censorship at state radio broadcaster Polskie Radio, which removed a chart-topping song criticising PiS chairman Jarosław Kaczyński. The affair prompted the resignations of employees and boycotts of the station by musicians.

The NGO also warned that in the last year “police repeatedly failed to protect journalists covering protests and used violence and arbitrary arrests to restrict the right to inform”. One such instance took place during protests against a near-total ban on abortion, when a journalist was forcibly detained by police.

Her treatment has been condemned by fellow journalists, opposition politicians and international rights groups, who say police acted in an unjustified and excessive manner. However, the police stated that she was detained on suspicion of the crime of violating the bodily integrity of a police officer.

Police were also accused of brutality against members of the press covering the annual Independence Day march in Warsaw organised by far-right groups.

Some journalists were beaten with batons, while a 74-year-old photographer, Tomasz Gutry, was injured by a rubber bullet fired by police. He required an operation in hospital to remove it.

The International Press Institute (IPI), a Vienna-based NGO, recently raised concern over an “increase in violence against journalists” in Poland. It also warned that the government is “waging a multi-pronged attack on independent media”.

Finally, RSF drew attention to the “black screen” protest staged by most of Poland’s leading private media earlier this year in response to a proposed new tax on advertising revenue, which is “seen as another step in the government’s censorship strategy”.

“With their finances already weakened by the pandemic’s economic effects, they [privately owned media] fear that the new tax will finish them off,” warn the authors.

RSF’s ranking is calculated on the basis of seven indicators, including pluralism, media independence, environment and self-censorship, legislative framework, transparency and infrastructure.

“This is now the frontline of defending Polish democracy”: five expert views on Poland media protest

Supporters of PiS argue that public media in Poland have always been under the influence of whichever party is in power and that the current conservative slant helps to balance out a media landscape previously dominated by more liberal outlets.

They also argue that private media were far from free under the previous government, led by the centrist Civic Platform (PO). In 2014, for example, security agents raided the offices of news magazine Wprost, using physical force to seize material as part of an investigation into the publication of secret recordings that had embarrassed the government.

The justice minister at the time, Marek Biernacki, admitted that prosecutors had gone “too far” in their actions against Wprost, which raised “legitimate concerns about breaching of journalistic confidentiality”.

3. However, conservative commentator Andrzej Nowak says that the pro-government bias of public media is a necessary "balance" against overwhelmingly anti-government private media.

"The situation in Poland [now] is incomparably better than it used to be" https://t.co/VlVquFHjqM

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 3, 2020

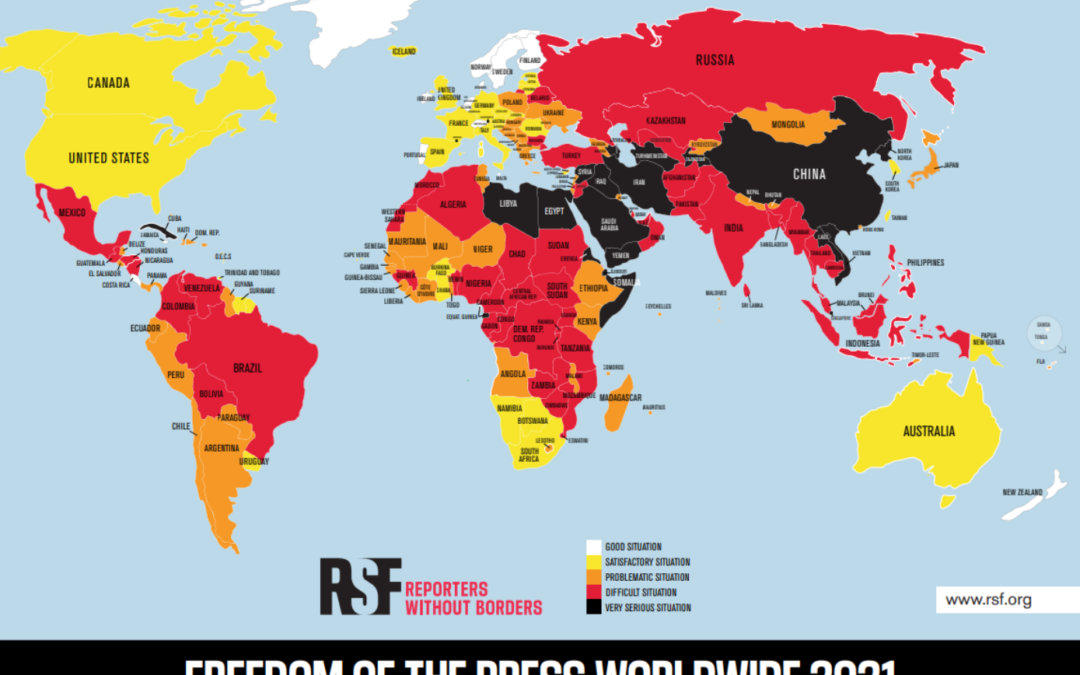

Main image credit: World Press Freedom Index, Reporters Without Borders

Agnieszka Wądołowska is deputy editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. She is a member of the European Press Prize’s preparatory committee. She was 2022 Fellow at the Entrepreneurial Journalism Creators Program at City University of New York. In 2024, she graduated from the Advanced Leadership Programme for Top Talents at the Center for Leadership. She has previously contributed to Gazeta Wyborcza, Wysokie Obcasy and Duży Format.