By Maria Wilczek

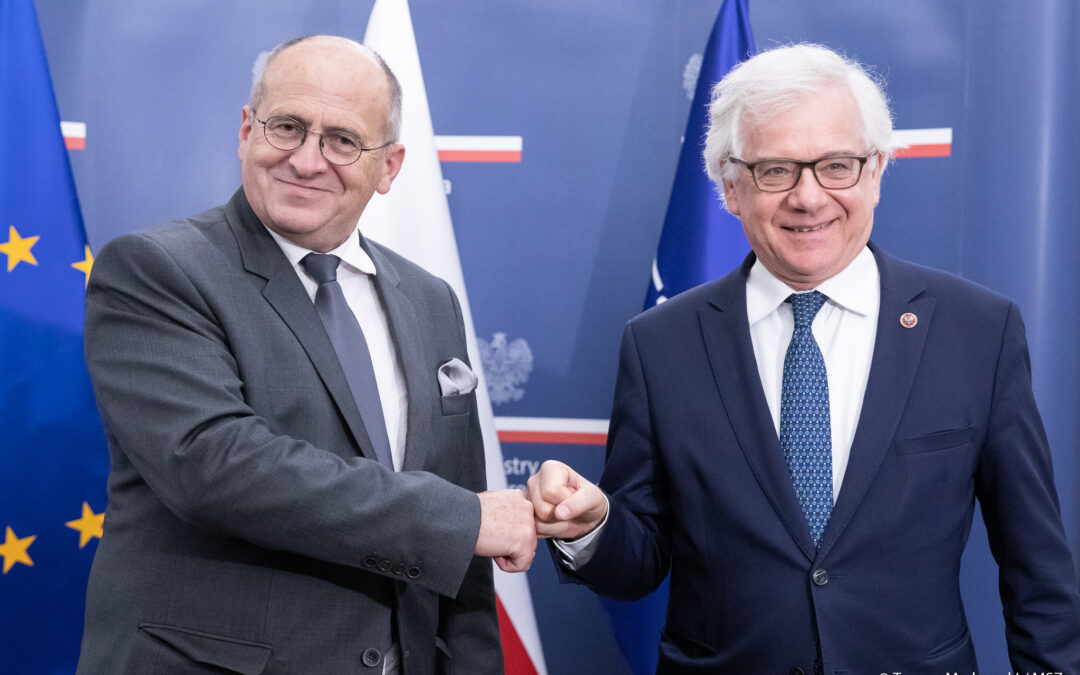

Zbigniew Rau was yesterday appointed as Poland’s new foreign minister, taking over from his predecessor of two and a half years, Jacek Czaputowicz, who announced his departure last week amid a flurry of government resignations.

Rau is a legal scholar, who has had stints at British and American universities. More recently, he has served as a member of both houses of parliament, the Sejm and Senate, for the ruling national-conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party, including being chairman of the Sejm’s foreign affairs committee for the last nine months.

His promotion to a ministerial role comes at a turbulent and sensitive time, amid a crisis in neighbouring Belarus as well as ongoing challenges over Poland’s relations with Brussels and its ambitions to position itself as a regional leader.

Recent anti-German comments from government figures – and Warsaw’s refusal for the last three months to accept Germany’s newly appointed ambassador to Warsaw – have also strained relations with Poland’s biggest neighbour and largest trading partner.

Questions will also be raised about Rau’s degree of authority and responsibility, after Czaputowicz’s term saw control over foreign policy drift towards the president and prime minister’s offices.

We asked six experts and insiders from academia, think tanks and politics to give their thoughts on what legacy Czaputowicz leaves behind, what his successor will make of it, and what the changeover means for Poland and its international partners.

Waszczykowski: “Changing minister every two years does not serve our interests”

“Neither of us received a full term – only two years [each],” begins Witold Waszczykowski, who served as foreign minister before Czaputowicz, from late 2015 to early 2018.

“Changing minister every two years does not serve the interests of the foreign ministry. A cycle [in diplomacy] is longer than that: in the first year you visit other countries, in the second, you host return visits,” explains Waszczykowski, currently a PiS MEP.

Waszczykowski believes that Czaputowicz’s term was less eventful than his own, as “the crucial issues were resolved in the first two years” of PiS government, which took power in 2015.

He also says that the foreign ministry’s policies have had to become more regionally orientated, as “issues of security have been taken over by the president’s circles, while European relations are now in the purview of the prime minister’s office”.

“I had hoped [Czaputowicz] would be more active in the Middle East,” he adds, also pointing to what he sees as Poland’s uneventful presidency of the UN’s Security Council in 2019.

Waszczykowski lists a number of strengths of the incoming minister, Rau. “He has spent many years living abroad. He is not afraid of the world, which he knows well.”

“He has been in politics for some time now – serving as a senator, member of the Sejm and provincial governor – so he has a good grip on domestic politics,” adds Waszczykowski. Czaputowicz, by contrast, had spent his career as an academic and civil servant, never having stood for elected office.

Asked about Rau’s criticism of “LGBT ideology” during an election campaign last year, which has received renewed attention following his nomination as foreign minister, Waszczykowski replies that “it is good he has a take on these things”.

“These issues are prominent in many countries, and have also reached us [in Poland],” says Waszczykowski. But he adds that Rau will not ultimately oversee such issues “because they are not to be dealt with by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs”.

Poland's new foreign minister last year campaigned for election by claiming that western countries were legalising paedophilia and bestiality

He also warned that a Swedish scientist advocated the legalisation of cannibalism as a solution to climate change https://t.co/wtJiIfU4mY

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) August 20, 2020

One of the first tasks facing the new minister is the stalled approval for Germany’s new ambassador, Arndt Freytag von Loringhoven, a former NATO intelligence chief and ambassador to the neighbouring Czech Republic.

His nomination has been left in limbo for the last three months, with the Polish government so far refusing to accept his appointment. German officials have suggested the delay is part of a political game by Warsaw, but the Polish side has accused Berlin of historical insensitivity for nominating the son of a former Wehmacht adjutant to Hitler.

“In Polish-German relations, the German side should be absolutely sensitive to us,” says Waszczykowski. “Diplomats along the Polish-German axis should be spotless – clean as a whistle – without family entanglements, so as to avoid ambiguous situations.”

“If there is no agreement after two or three months, a new candidate is sent. Let’s not look for ulterior motives,” he concludes.

Mieńkowska-Norkiene: “Rau will be expected to clean up”

“Poland’s foreign policy has been hostage to its domestic politics,” says Renata Mieńkowska-Norkiene, an associate professor of political science at the University of Warsaw.

“During the time when Jacek Czaputowicz was minister, Zbigniew Ziobro [the justice minister] tried to influence foreign policy,” she notes, pointing to two examples: the amendment to the Act on the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN), widely referred to as the “Holocaust law”, and the more recent question of withdrawing from the Istanbul Convention.

Mieńkowska-Norkiene anticipates that Rau’s appointment will encourage Poland’s hardline justice minister to further meddle in foreign affairs. “Rau is more oriented towards what Ziobro expects, with a strong ideological background,” she says.

In coming months, one such area will be the proposed linking of funds in the EU’s next budget to observance of rule-of-law criteria. “Rau will not normalise relations with the EU,” says Mieńkowska-Norkiene, noting his “anti-European discourse”.

She also believes that the appointment could undermine Poland’s diplomatic efforts in Belarus. “Rau does not really accept the values on which the EU is based – particularly equality, inclusion and freedom of thought and lifestyle,” she explains.

“It doesn’t look serious when such a person is appointed at time of crisis in Belarus, which is mostly about accepting European values, such as democracy and freedom.”

Mieńkowska-Norkiene also believes that Rau will have a further role to play at the foreign ministry: “The expectation of Jarosław Kaczyński [PiS’s powerful party leader] is that Rau will decommunise diplomacy.”

“Jacek Czaputowicz did not do that, because he knew that if he got rid of good diplomats – even if they worked for the Communist apparatus before 1989 – he would lose much of the ministry’s human capital,” she says. “Rau, however, will be expected to clean up.”

Dębski: “The challenge will be moulding relations with the new US administration”

Sławomir Dębski, director of the Polish Institute of International Affairs (PISM), a public think tank, says the change comes “at a natural moment. The [presidential] election period is over. We had a new mandate in the whole cycle, there comes a moment of reflection on personnel decisions.”

“Rau is a different kind of personality, with a different baggage of experiences,” says Dębski, extolling Rau’s academic background as a way of “charging the intellectual batteries” of the ministry.

“He’s an interesting – outstanding, even – intellectual who specialises in political and legal doctrines,” says Dębski. “Career diplomats do not have the luxury of extensively considering such issues.”

“The minister is not a satellite, but a part of the state apparatus that deals with the implementation of the current government’s policy. It is impossible to replace or bypass the foreign ministry, which [in terms of foreign affairs] is the intellectual backbone of the government.”

Yet Dębski says he would not “expect radical change”, which he says is mostly driven by external events and international institutions.

“The challenge ahead will be to mould our relationship with the new US administration – even in the case that it is a second Trump administration. The Americans are reconsidering their commitments around the world, and these are extremely important from our perspective,” adds Dębski.

Traczyk: “The ministry now plays a marginal role in Poland’s foreign affairs”

“Under normal circumstances, the timing of the change would be shocking, given the crisis in Belarus weighing on the vital interests of the Polish state” begins Adam Traczyk, head of the Global.Lab think tank in Warsaw and previously a European parliamentary candidate for the left-wing Wiosna party.

“On the other hand, Czaputowicz and the entire Ministry of Foreign Affairs now play a marginal role in Poland’s foreign affairs, its position has been relegated over the past two years,” he continues.

According to Traczyk, much of the foreign ministry’s role in European politics has been shifted to the prime minister’s office, while transatlantic policy-making has been transferred to the president, leaving the ministry as “an administrator of day-to-day business, without any strategic dimension.”

He anticipates that Rau will continue the current course of the ministry. “Internally, he has a stronger position than that of Czaputowicz. He is more embedded in party structures, but also has more personal connections with the Kaczyński family and its milieu. However, at the same time, he also does not reveal any greater ambition to impose his own agenda.”

Traczyk also notes that the stalled approval for Arndt Freytag von Loringhoven “is clearly weighing on relations” with Germany:

This situation embarrasses Poland. The nomination of ambassadors should be done with great mutual trust. The Polish side must have given the informal green light [for Germany] to apply for the agrément [approval of the ambassador]. If Poland would like to withdraw its consent, it should be done confidentially – while here there were leaks to the media. It seems evident that this is a decision imposed by Nowogrodzka [PiS headquarters].

Zaborowski: “Poland needs a more active Eastern policy”

“The appointment of Zbigniew Rau means a new opening, which is much needed at this point in time,” says Marcin Zaborowski, a lecturer in political science, editor of Res Publica Nowa, and former director of PISM.

“Rau is more involved in the PiS inner circle, which means that there is a chance that he will be freer to show more initiative. Whilst Czaputowicz moderated previously chaotic foreign policy, Rau can now afford to make it more active.”

Zaborowski does not, however, expect the change to lead to any reassessment of priorities. “There is a chance that the Poland-France-Germany ‘Weimar Triangle’ will be revitalised, though the recent dispute about Germany’s ambassadorial appointment in Poland is an unnecessary distraction”.

He sees Czaputowicz’s legacy as a mixed bag. “On one hand, there is no doubt that he moderated foreign policy and reassured allies…Relations with the EU have not returned to normality, but they started to be less adversarial and freer of unnecessary conflicts,” says Zaborowski.

“A very positive aspect of Czaputowicz’s foreign policy was an improvement in relations with Lithuania,” he adds. “However, it was clear that some major decisions concerning foreign policy, including many aspects of EU relations and relations with West European partners, were decided outside the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, by the prime minister or Kaczyński.”

“At some point it became apparent that the ministry refrained from initiating new approaches in fear that they may be resisted and overruled. As a consequence, foreign policy has become quite passive – as evidenced in the face of the Belarus crisis, where Lithuania, ten times smaller [than Poland], is more active than Poland, which once led EU Eastern policy.”

“After the years of passivity, Poland clearly needs a more active Eastern policy. It is unnatural that Poland doesn’t lead EU initiatives towards Belarus,” says Zaborowski.

Żurawski vel Grajewski: “A shift in emphasis towards to the Anglo-Saxon world”

Przemysław Żurawski vel Grajewski, a professor of political science at Łódź University and an adviser to Czaputowicz, says that the outgoing minister’s term came during a “hard time”.

“There were elections: European, then parliamentary, and then presidential. It was a period of raging dispute with the European core, including over the EU’s multiannual budget, then eclipsed by the coronavirus pandemic,” Żurawski vel Grajewski told Notes from Poland.

He sums up Czaputowicz’s legacy as being focused on regional cooperation (with the Baltic states, Visegrád Four, Romania, Ukraine, Georgia) that resulted in:

a breakthrough in relations with Lithuania, an active regional policy focusing on the Western Balkans European integration process, and significant progress in relations with Ukraine – leading to the creation of a new format of interstate cooperation [the so-called Lublin Triangle of Poland, Lithuania and Ukraine].

In Rau, Żurawski vel Grajewski sees continuation, “because the current policy is not a personal one.” He adds, however, that there could be “a shift in emphasis towards the Anglo-Saxon world” at the foreign ministry as a result of Rau’s academic past at the University of Texas at Austin and at Trinity College at the University of Cambridge. Up until now, such relations have largely been the domain of the president’s office.

The focus of coming years will be a “strategic alliance with America, both in the military and energy dimension”, as well as a possible push in relations with post-Brexit Britain and cooperation with Central European neighbours, he concludes.

Congratulations to @RauZbigniew on today’s official appointment to Minister of Foreign Affairs @MSZ_RP. Minister Rau, I know that our cooperation will further enhance Polish-American relations. All the best in your new role!

— Georgette Mosbacher (@USAmbPoland) August 26, 2020

Main image credit: Foreign Ministry/Twitter

Maria Wilczek is deputy editor of Notes from Poland. She is a regular writer for The Times, The Economist and Al Jazeera English, and has also featured in Foreign Policy, Politico Europe, The Spectator and Gazeta Wyborcza.