Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Daniel Tilles and Andżelika Cibor

In this year’s presidential election, young Poles were much more likely to vote than their older compatriots, setting the country apart from many other democracies.

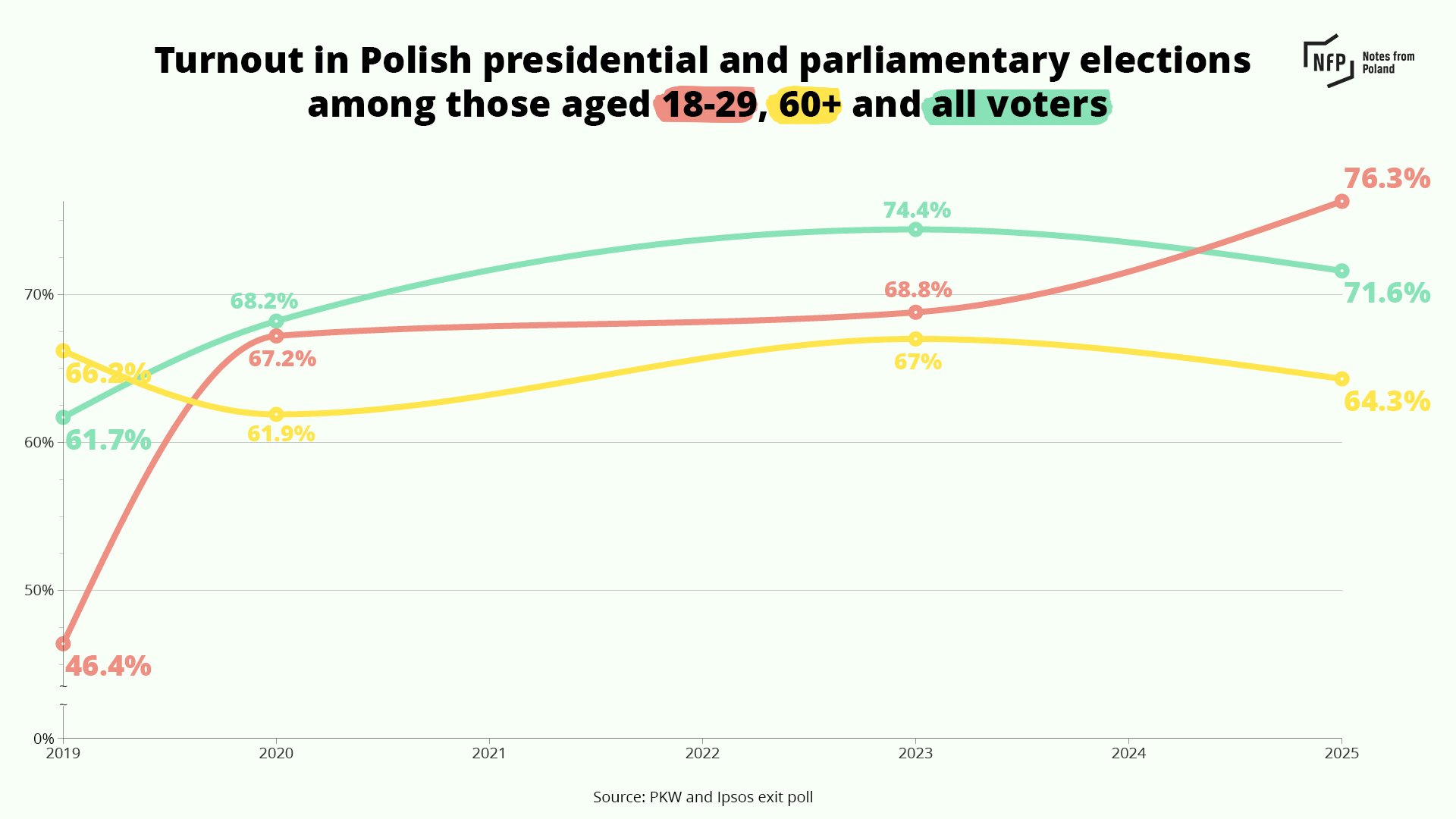

In the second-round run-off on 1 June, 76.3% of Poles aged 18 to 29 came to the polls, compared to 64.3% of those aged 60+.

By contrast, in last year’s US presidential election, only 47% of 18-29 year olds voted while 74.5% of those aged 65+ turned out. The pattern was similar at the UK general elections in 2023, where 73% of those aged over 65 voted, while among the youngest category, 18-24, just 37% did so.

Moreover, the high youth turnout at Poland’s recent presidential election was not an anomaly but part of a longer-term trend.

In the 2019 parliamentary elections – the first at which there are data for voting by age – Poland’s pattern conformed to the international norm, with the oldest voters having much higher turnout (66.2%) than the youngest ones (46.4%).

However, since then, the pattern has reversed, with younger Poles voting in greater numbers than older ones at the subsequent three presidential and parliamentary elections. This year, for the first time, youth turnout even exceeded overall turnout.

The “breakthrough year” of 2020

Dominik Kuc of GrowSPACE, an NGO that works to support young people’s human rights and wellbeing, believes that 2020 was a “breakthrough year” for youth engagement.

That period saw mass “Women’s Strike” demonstrations – disproportionately made up of young Poles – against the tightening of the abortion law. Around the same time, many young people became engaged in the response to the conservative Law and Justice (PiS) government’s aggressive anti-LGBT campaign.

Data from state research agency CBOS show a huge jump in 2020 in the proportion of young people who reported taking part in a protest, which rose to a record high of 23.8%, up from 6.6% in 2019. By contrast, among all Poles, the figure rose from 6.5% to 8.3%.

Left-wing views among young Poles have reached their highest ever level in regular polling conducted since the fall of communism in 1989.

For the first time, left-wing views are stronger among the young than both right-wing and centrist ones https://t.co/bn95iYTOIe

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 8, 2021

Kaja Gagatek, co-author of the recent State of Youth report published by Ważne Sprawe, an NGO involved in encouraging civic participation among young people, believes that mass protests in recent years have helped “empower” and “mobilise” young people.

“These kinds of events built a belief in young people that politics has an impact on their daily lives,” says Gagatek. As a result, “now they are actively participating in elections”.

That is a view reflected in the experience of Oliwia Kotowska, a first-time voter this year who says that her “political awareness began with the Women’s Strike in 2020”, when she was aged just 13.

Kuc, meanwhile, also notes that the politicisation of the school system under PiS – which sought to clamp down on sex education, strengthen Catholic teaching, and block LGBT+ events – helped bring politics more directly into the lives of young people.

The children’s rights commissioner has announced an inspection of schools recently ranked as the most LGBT-friendly in Poland.

He wants to ensure principals "check employees against the register of paedophiles" so "children are protected from criminals" https://t.co/yGPzGeZ3BT

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 24, 2023

That position is shared by Natalia Nizołek, aged 19, another first-time voter in the recent presidential election. She says a turning point for her was the PiS government’s introduction of a new subject, known as History and the Present, to schools, which she says was “full of really bad propaganda”.

“That change was the most visible one in my own life,” she says, and helped her see government policy as something deeply personal.

Frustration with the mainstream

The sense of agency among young voters was then further amplified in 2023, when they played a key role in voting PiS out of office in that year’s parliamentary elections, which brought a new, more liberal coalition to power.

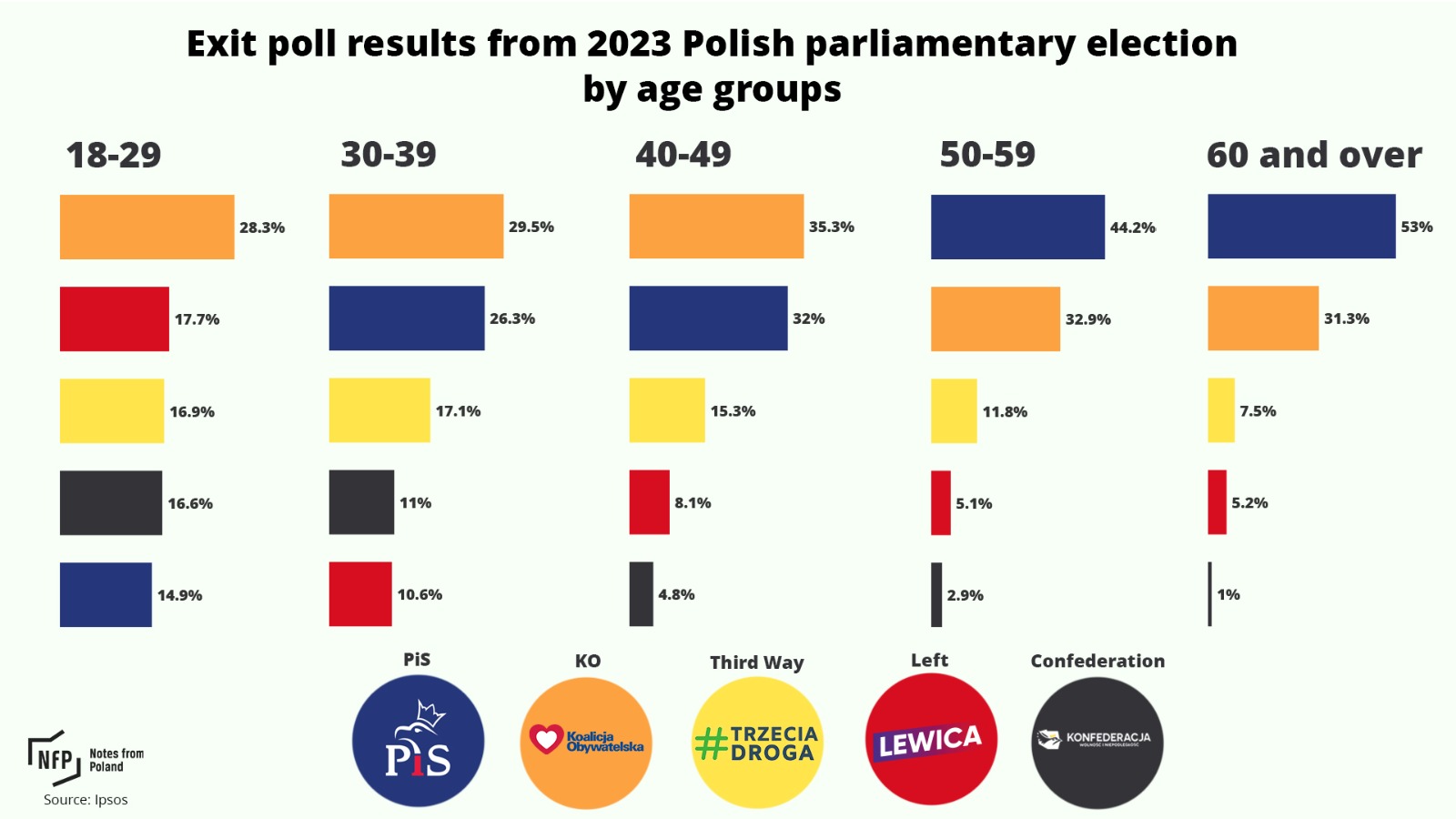

At those elections, the most popular choices among young voters were the groups that came to form the new government: the centrist Civic Coalition (KO), which took 28% of their votes; The Left (Lewica), which got 18%; and the centre-right Third Way (Trzecia Droga) on 17%.

PiS was the least popular party among young voters, with 15%. By contrast, among every other age group, it was the first or second most popular party, winning over half of votes among those aged 60+.

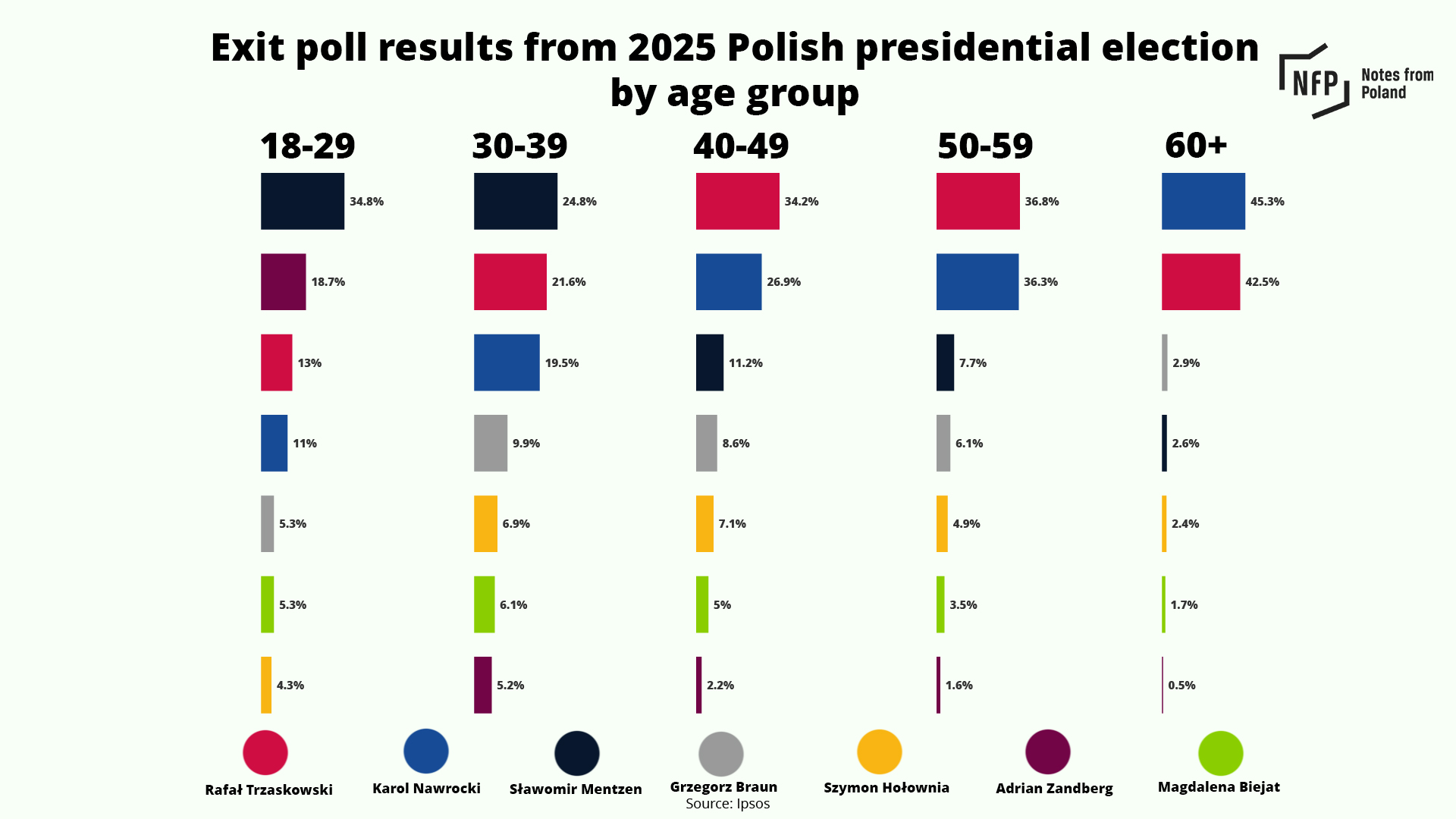

However, by this year’s presidential vote, things had changed significantly, with young people now increasingly turning away from the mainstream and looking to the right- and left-wing extremes of the political spectrum.

In the first round of that election, the candidates of KO and PiS – Rafał Trzaskowski and Karol Nawrocki – received only 24% of votes from those aged 18-29. By contrast, among those aged 60+, they got 88%.

The two most popular candidates with young voters were Sławomir Mentzen, of the far-right Confederation (Konfederacja) party, who got 35%, and Adrian Zandberg of the small left-wing Together (Razem) – which last year cut ties with the more centrist Left – who got 19%.

Michał Mazur, coordinator of a youth voting project at the Centre for Citizenship Education, a Warsaw-based NGO, believes that young people, who already had a low opinion of PiS, have since 2023 also been stung by the broken promises of the new ruling coalition.

Pledges to increase the income-free tax threshold, introduce financial support for young people buying or renting homes, liberalise the abortion law and strengthen LGBT+ rights are among the dozens that have not been implemented.

“This coalition did not deliver on very important promises for young people, so they voted against them in this presidential election and let them know ‘we will not accept politicians not being interested in us’,” says Mazur.

Kuc agrees, noting that “there is growing frustration with the current government’s inability to address certain issues” important to young people.

Polls conducted to mark one year since @donaldtusk took power show that most Poles negatively assess the work of his government so far and many more feel their lives have got worse than better.

Women and young people are particularly disappointed https://t.co/QWZWvbyQbW

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 13, 2024

The fact that young Poles are being drawn towards the extremes of the political spectrum may seem concerning. But Mazur offers a different perspective. For them, it is actually PiS and Civic Platform (PO), the dominant force in KO, who seem like extremists, he says.

The two parties – which have led every Polish government for the last 20 years – have long been locked in a bitter struggle for power, using aggressive rhetoric against one another and warning that the other side will bring about the destruction of Poland.

“The young feel that they already live within the radicalism of this political dispute,” argues Mazur. “So they now have a tendency to vote for candidates who are further removed from [it].”

Young people see the KO-PiS conflict as “a dispute between their parents and their grandparents”, says Maciej Popławski of Youth for Freedom (Młodzi Dla Wolności), the youth wing of Mentzen’s party. “They don’t feel part of it.”

Popławski argues that, despite their bitter rhetorical attacks on one another, the two main parties in fact differ little from one another in practice on many major issues.

Meanwhile, when it comes to making the kind of “extreme” changes that young people are seeking – on things like housing, education and taxes – the mainstream parties fail to take meaningful action.

Popławski believes that Confederation has been able to harness the youth vote by focusing directly on such things. Zandberg, too, devotes much of his energy to social and economic issues that are most relevant to the young.

Aleksandra Iwanowska, who is vice-president of both Poland’s Young Left (Młoda Lewica) and the Young European Socialists, says that, for her growing up, politics was always about “two big, rather ideologically undefined camps…fighting and not resolving, not progressing”.

“The very frustrating realisation was that I really did not feel either represented, or understood, or seen by either of those [camps],” she adds.

Anyone born this century only has memory of living under PO and PiS rule, points out Gagatek, and “young people feel neglected by the political parties that have governed so far”.

When they see “a state that’s malfunctioning, public institutions that are malfunctioning”, they are drawn towards parties like Confederation and Together who, “first of all, have never governed and seem to offer a great alternative, and secondly, and most importantly, seem to actually notice young people and their problems in their programmes”.

Over half of voters aged 18 to 29 supported candidates of the far right and left in the first round of Poland's presidential election.

We spoke with young voters and experts to find out what is behind this rejection of the political mainstream https://t.co/ebCGHhAcFN

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 30, 2025

Why, in that case, do mainstream parties not follow suit? One reason is Poland’s disastrous demographics, which mean there are fewer and fewer young people.

Following a postwar baby boom, and another in the 1980s, the fertility rate has been in decline: from almost 3 children per woman in 1960, to 2.4 in 1982 and just 1.22 in 2002. Last year, it reached a new record low of 1.1.

“This is a very small electorate, and so, for pragmatic reasons, it’s no wonder that these major parties aren’t interested in these young people,” says Gagatek.

A gender divide

Meanwhile, young voters are also divided by gender, with men disproportionately attracted to the far right and women tending towards liberal and left-wing options.

Kuc believes that “the problems faced by young men in Poland have been completely neglected by progressive and centrist parties, who haven’t presented any answers to them”.

He notes that young men are much more likely to commit suicide than their female counterparts and puts this down in part to Poland’s relatively conservative, patriarchal society, which places expectations on young men that are increasingly hard for them to meet.

A record number of suicide attempts by children and adolescents have been recorded in Poland this year

Police data show over 1,500 by the end of September, already more than in the whole of 2021.

For more, see our report: https://t.co/cBthaVVBhM pic.twitter.com/VxDU93a1LM

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 27, 2022

Popławski, the young Confederation activist, offers his own take on this: “Young men want to experience adventure: slay the dragon and win over the princess.” This, he argues, draws them to the sense of freedom and self-responsibility offered by his party’s economic libertarianism.

Kuc, meanwhile, notes that young women have felt particularly let down by the current government’s complete failure to implement its promises to liberalise abortion laws – one of the main factors that motivated them to vote PiS out of office in 2023.

As a result of their disappointment, “many young women simply shifted their votes even further to the left” in the recent presidential election, says Kuc.

A year ago, polling showed that the highest level of dissatisfaction with the government for failing to liberalise the abortion law was found among Poles aged 18-29, 51% of whom were disappointed, rising to 57% among women aged 18-39.

Almost half of supporters of Poland’s ruling coalition are disappointed it has not followed through on its promise to liberalise the abortion law.

The same poll shows that over half of young Poles – who voted in record numbers last year – are disappointed https://t.co/6hAqQ7a5LE

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) June 20, 2024

Social media driving engagement

All of our interlocutors also highlight the importance of social media in driving youth engagement in politics.

According to Reuters Digital News Report 2025, 54% of Poles access news via social media – a six-point increase from the previous year and a much higher figure than in the UK (39%), France (37%) and Germany (33%).

For many young users, these channels have entirely replaced traditional media as the main way of following current events, including elections.

This shift was clearly visible during the recent presidential campaign, where fragments of TV debates, often edited for maximum impact, spread widely online. Clips, memes and commentary circulated rapidly through social feeds, turning political messaging into something more dynamic and accessible.

This made the election into “a kind of political reality show”, says Mazur, with candidates judged not just – or even mainly – by their programmes, but by how they perform in front of a digital audience.

Many voters “didn’t necessarily vote by ideology, but for the candidate who convinced them more on TikTok”, agrees Kuc.

Candidates who understood this stood to gain. Mentzen, who is the most-followed Polish politician on TikTok, and Zandberg built their popularity among youngsters with a strong presence on social media.

Poland's conservative ruling party has joined TikTok, saying it will challenge the "radical anti-PiS messages flooding social media"

It is the last of Poland's major parties to join the platform, where they are campaigning ahead of this autumn's elections https://t.co/7lhU2iyKDo

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 16, 2023

Social media helps spark real-life discussions, by bringing political content directly into young people’s private spheres, shaping awareness and reinforcing the sense that politics is something happening around them, every day, points out Gagatek.

Her organisation’s recent report on young Poles found that 80% believe that activism and social action can change the world – a figure that was so high it surprised even her.

Kuc, meanwhile, believes that the record youth turnout in this year’s presidential election may drive engagement even further.

In the second-round run-off, Trzaskowski won among voters aged 40+, according to exit polls, but Nawrocki was more popular among those below that age. His biggest margin of victory was among the youngest voters, aged 18-29, where he had a four-percentage-point lead over his rival.

In what ended up being the closest presidential election in Polish history, with Nawrocki winning with 50.9% to Trzaskowski’s 49.1%, those youth votes were vital. This, says Kuc, gave many young voters, especially those with right-wing sympathies, a feeling of “power and agency”.

As the three most recent parliamentary and presidential elections have shown, young Poles’ engagement is no one-off. And, with PO and PiS continuing to be the dominant forces in Polish politics, the frustrations that have driven high youth turnout look set to continue – and perhaps grow even further.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Jakub Orzechowski / Agencja Wyborcza.pl