Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

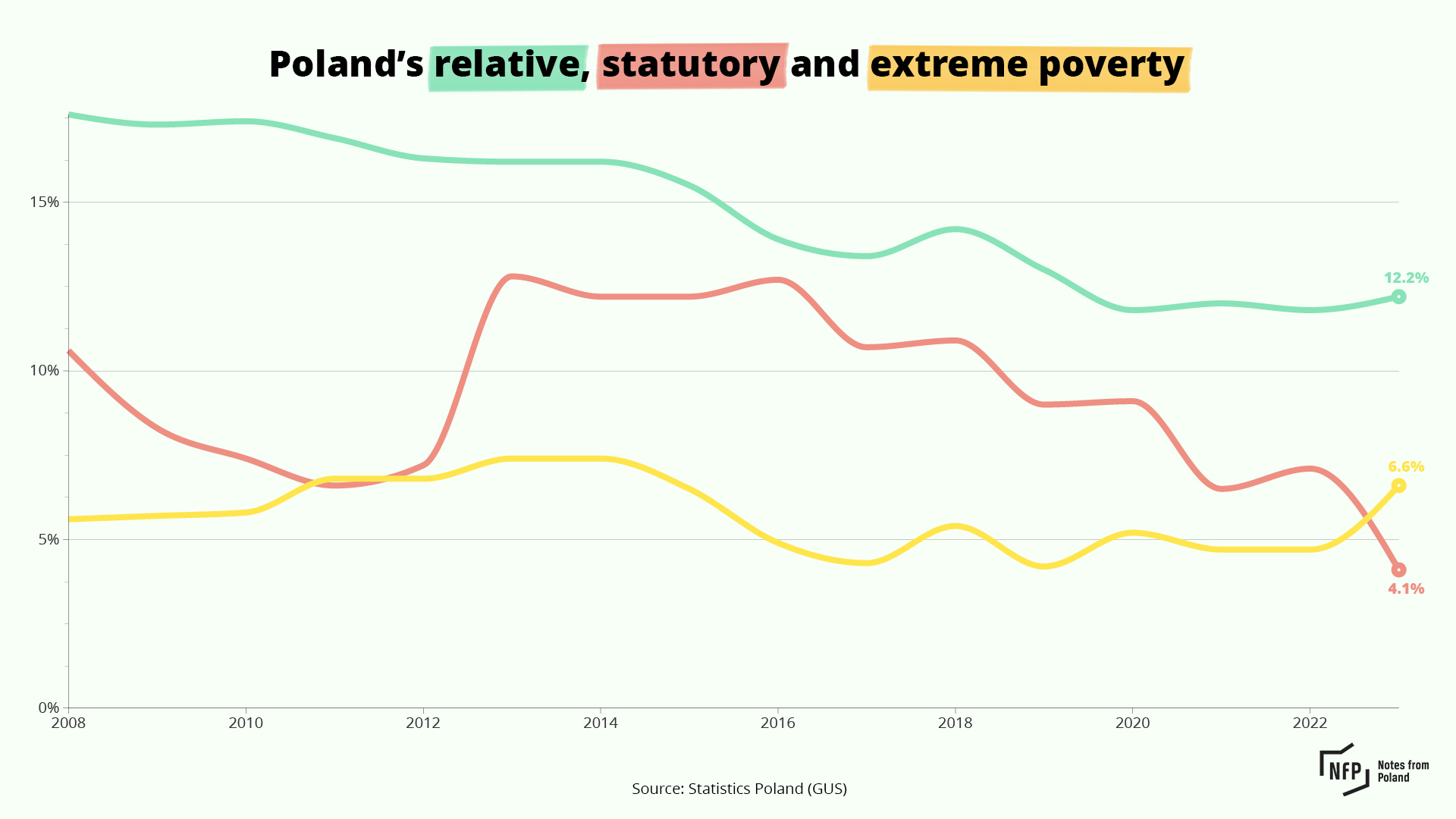

Around 2.5 million people lived in extreme poverty in Poland in 2023, equivalent to 6.6% of the country’s population, a new report by the Polish branch of the European Anti-Poverty Network (EAPN) shows. That figure rose 47% compared to the previous year and reached its highest level in almost a decade.

EAPN ascribes the rise to Poland’s economic situation, in particular persistently high inflation, which reached a 26-year high of 18.4% in early 2023. But it also warns that “systemic problems in social policy” have left many struggling, in particular families with children, seniors and disabled people.

The network has called on the authorities to introduce automatic indexation of benefits and to create a more “coherent system of income criteria”, because the current system results in some people who live in extreme poverty being above the statutory poverty threshold to qualify for support.

EAPN’s latest annual report, based on data from Statistics Poland (GUS), a state agency, found that from 2022 to 2023, the number of people living in extreme poverty rose from 1.7 million (4.6% of the population) to 2.5 million (6.6%). Among children, the extreme poverty rate was even higher, at 7.6% in 2023.

Extreme poverty is defined as a level of spending below a threshold of minimal subsistence calculated by the Institute of Labour and Social Studies (IPiSS), a government research institute. In 2023, the extreme poverty threshold was 901.04 zloty (€208.90) per month for a one-person household.

The number of people living in “relative poverty” – which is defined as 50% of the average spending of households in Poland – also increased in 2023, but to a lesser extent, from 11.7% to 12.2%, and affected 4.6 million people.

However, the level of “statutory poverty” – relating to people whose income level entitles them to claim social assistance – fell by around two percentage points to 4.1%. But that was mainly because the thresholds to quality for aid remained unchanged from the previous year.

Meanwhile, the proportion of people living in social exclusion – defined as those severely materially deprived or living in households with very low work intensity – increased considerably from 41.1% in 2022 to 46% in 2023, when it affected 17.3 million people.

“Last year, we warned that the mix of the poor economic performance and continued high inflation, combined with no change in the levels of social benefits and eligibility criteria for these benefits, would result in a drastic deterioration in poverty rates,” said Ryszard Szarfenberg, the head of EAPN Poland.

He noted that the increase in poverty among the most vulnerable social groups – children, seniors and people with disabilities – is “particularly worrying”. According to Szarfenberg, this “points to systemic problems in social policy.”

Aby zatrzymać dalsze wzrosty #ubóstwo, konieczne są pilne zmiany https://t.co/KJ1xUU2cRa. w sys. św. społ. – pomocy społ., św. rodzinnych i #800plus. Mamy nadzieję, że planowane reformy zapewnią budowę odpornego systemu wsparcia społ. Pełna lista rekomendacji w #PovertyWatch 2024 pic.twitter.com/iHidpvzlSu

— EAPN Poland (@EAPNPoland) October 17, 2024

The level of poverty in Poland has generally been falling since 2015, when the national-conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party came to power and implemented a range of new social welfare policies.

Its flagship programme was a monthly child benefit of 500 zloty that was introduced in 2016. The level of the payout remained the same over the following seven years, until PiS left office at the end of 2023.

However, from the start of this year it was raised to 800 zloty per month – a change that was announced by PiS while it was still in government but implemented by the new administration that replaced it last December.

Poland's ruling PiS party has announced a rise in its flagship child benefit scheme from 500 to 800 zloty per month as it campaigns for a third term.

It has also pledged free medicine for children and seniors and the end of tolls for using motorways https://t.co/S2Iek3tYHF

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 14, 2023

In its report, EAPN called for the “automatic annual indexation of the child benefit, family benefits and social assistance as a permanent ‘anti-inflation shield’ for the poorest”.

It also appealed for “the introduction of a coherent system of income criteria for benefits” because “in 2022 and 2023, there was a situation in which the statutory poverty line was lower than the extreme poverty line, meaning that some extremely poor people were not entitled to social assistance benefits”.

The current government has pledged to not only retain the benefits established by PiS but also to expand them. It has already introduced a handout – informally called “granny payments” – that provides financial support to help parents of young children return to work.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Grzegorz Celejewski / Agencja Wyborcza.pl