By Maria Wilczek

The communist era left little room for architectural sentimentality. Its revolutionary energy took to rebuilding war-ravaged cities on a modern grid of spacious avenues and monolithic communal buildings. The return of democracy in the 1990s again saw Poles looking forward, rather than back, with new buildings and architectural styles emerging.

Yet with a rich heritage and growing confidence to build on it, recent years have seen a trend towards reclaiming and repurposing historical buildings. These sites include disused factories, abandoned palaces, defunct train stations and communist-era hotels, which have been renovated for a new generation of Poles.

Following up on our list of abandoned spots to visit in Poland, below we present eight of the most interesting reclaimed sites and objects across the country, from former synagogues to Warsaw’s neon signs.

1. Eating on a train platform in Warsaw

In 1975, trains rattling into Poland’s capital were redirected to the new Warszawa Centralna station. The emptied platforms of Warsaw Main Station, which had been rebuilt at the end of the Second World War, were slowly relegated to the stuff of pop songs.

However, since 2016, boisterous whistles and hurried footsteps have returned to the area. It has now become the site of the weekly “Night Market” event, which hosts dozens of international food stalls, bars, live music and increasingly also services like barbershops and tattoo parlours.

In March, the partially renovated station was returned to use for trains after 24 years. However, the market has now become a mainstay, opening up for its next summer season this weekend.

Night Market in former Warsaw Main Station (source: Nocny Market/Facebook)

Night Market in former Warsaw Main Station (source: Nocny Market/Facebook)

Down the train line heading east, the former ticket booth at the still-functioning station PKP Powiśle has also been turned into a bar. As summer begins, tens of deckchairs are already spilling out onto the cement patch squeezed between busy roads and rail lines.

Former ticket booth at the PKP Powiśle station (source: Powiśle Warszawa/Facebook )

2. Raving in a brutalist ballroom in Kraków

When it first opened in 1989, the Hotel Forum seemed like a place from the future. The first computerised hotel in the still-communist country surprised guests with modern luxuries, such as air-conditioned rooms and an advanced telephone system.

Its stilted modular brutalist body looms over the Vistula river in Kraków and stands in sharp contrast to the Wawel Royal Castle – with its mix of Romanesque, Gothic and Baroque features – on the opposite bank.

Hotel Forum in 2002 (source: AirBeagle/Flickr, under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The abandoned Hotel Forum in 2016 (source: Artur Salisz/Flickr, under CC BY-NC 2.0)

In 2002, however, the hotel closed over safety concerns. After a decade of silent deterioration, the cement structure has been transformed into one of Kraków’s liveliest and hippest nightspots, featuring a bar in the former reception and deckchairs on the bank of the river.

A new bar in the former Hotel Forum (source: TEDxKrakow/Flickr, under CC BY 2.0)

Outdoor drinking at the former Hotel Forum (source: Forum Przestrzenie, promotional material)

The hotel has also been used as a venue for Kraków’s annual Unsound electronic music festival, a week-long rave for “emerging, experimental, and leftfield” music that takes place in the brutalist ballrooms and kitchens of the hotel.

We sent Grant Armour (@avantgrant) to a rave in an abandoned Communist hotel in Poland, because we like to do that sort of thinghttps://t.co/bVdR7cI8eC

— Amuse (@AmuseLife) November 29, 2018

Another leading Polish music festival, Open’er, takes place in a former military airport near the coastal city of Gdynia.

Its more than 100,000 attendees roam the grassy landing strips to beats from the likes of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Rihanna, and Jay-Z, sipping watery Heineken beer and wandering around outdoor art galleries and film screenings in abandoned airfield hangars.

3. Picking up groceries from the synagogue in Inowłódz

The two-storey white building once served the Jewish third of the population of Inowłódz as a prayer house. Its walls are decorated with what are believed to be Poland’s last surviving painted prayers for the ruler, next to possibly the country’s oldest zodiac inscriptions. But the spacious interior is now lined with supermarket aisles.

Former synagogue in Inowłódz (source: Autostopowicz/Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 3.0 PL)

Inside the former synagogue in Inowłódz (source: Tomasz Stanczak / Agencja Gazeta)

Before World War Two, Poland had over three million Jews – Europe’s largest Jewish population. After the Holocaust, only a tiny fraction remained. While some Jewish heritage has been preserved, much of it has been repurposed, with synagogues becoming libraries, post offices and workshops.

The compact 18th-century synagogue in Sandomierz became a municipal archive in 1965. Opoczno’s synagogue was turned into a cinema and now serves as a window factory. Last year the local authorities in Banie in northwestern Poland decided to turn their crumbling brick temple (which had previously served as a manure depot as well as a firehouse) into a nursery.

Some projects have proved controversial, such as the bar that opened amid the surviving frescoes of the Chevra Tehilim prayer house in Kraków, sparking debate among the city’s Jewish community, whose leaders leased out the building.

Former Jewish prayer house in Kraków (source: Hevre Kazimierz/Facebook)

Interior of former Jewish prayer house in Kraków (source: Hevre Kazimierz/Facebook)

4. Coding in a vodka distillery in Warsaw

Where once stood giant kegs of fermenting wheat, now Google’s software engineers tap away at their keyboards. In 2015 the neo-gothic Koneser (Connoisseur) vodka distillery became the site of the first Google Campus in Poland, which serves as a tech coworking space.

Former Koneser vodka factory, Warsaw (source: Wistula/Wikimedia commons, under CC BY 3.0)

Big developers are increasingly seeking to integrate layers of history into office space design, rather than tear down all that escapes the attention of conservators.

Former warehouse now used as Google campus (source: Adrian Grycuk/Wikimedia commons, under CC BY-SA 3.0 PL)

Inside the campus (source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs/Flickr, under CC BY-NC 2.0)

In a keenly awaited new coworking space opening on the other bank of the Vistula, Browar Warszawski (Warsaw Brewery) will fill the site around the beer factory with 50,000 square metres of office space and 4,000 square metres of apartments. The 170-year-old cellars will house cafes, restaurants, as well as – true to its name – a smaller-scale brewery.

5. Living in a princely palace in Lower Silesia

Across Poland, hundreds of palaces come with rich histories, often obscured by their repurposing as accommodation, offices and storage space during the communist era. History enthusiasts and hotel owners are now polishing such gems, which usually take years of work and hefty budgets to fix up.

Manor house in Piotrowice Nyskie (source: Piotrowice Nyskie Palace/Facebook)

One such palace in Lower Silesia is the 17th-century manor house in the village of Piotrowice Nyskie, near the border with the Czech Republic, owned by former London-based journalist Jim Parton and his Polish wife Anna. “It’s big, but not Versailles”, Jim told Notes from Poland.

Manor house in Piotrowice Nyskie (source: Piotrowice Nyskie Palace/Facebook)

Manor house in Piotrowice Nyskie (source: Jim Parton/private archives)

Parton moved to Poland 16 years ago to become king of the castle for “less than the price of a one-bed flat south-east London”. Built in 1660 for a local bishop and then given a classical makeover in 1829, the abandoned palace has now become a venue for weddings and music events.

The best business comes from hosting reunions and group trips. Mainstays in its calendar include Blues and Tango dance camps, an international rugby festival as well as an annual retreat for the German Pirate Party.

Manor house in Piotrowice Nyskie (source: Piotrowice Nyskie Palace/Facebook)

However, according to Parton, the allure of some neogothic facades that pop up on online listings can be misleading. Finding the right one is tricky. “Either they are devastated, or next to a pig farm, or have previously been an institution, such as an agricultural college, village school, psychiatric or rehab residence.”

What a gem: 19th century palace in the village of Kopice, now in ruins scattered amid frozen ponds pic.twitter.com/KqZu9heHkf

— Maria Wilczek (@mariawilczek) February 20, 2021

6. Sleeping in a Tsarist train in Białowieża

Russian Tsar Alexander III grew so fond of the lush forests around Białowieża in eastern Poland that he decided to make the primeval forest his personal hunting grounds. His son later ordered the building of a train station to service the newly built palace. Trains rattled down the forest track until 1992.

Today the hidden-away wooden “Białowieża Towarowa” station hosts a restaurant with local cuisine from the Polish-Belarusian borderlands, including Solyanka soup, Siberian pielmieni dumplings and local game. The train carriages that were left abandoned on the tracks have been redecorated as a luxurious set of four sleeper wagons.

A room in a former sleeper wagon (source: Restauracja Carska i Apartamenty/Facebook)

The exterior of the train (source: Carska.pl)

7. Shopping in a cotton mill in Łódź

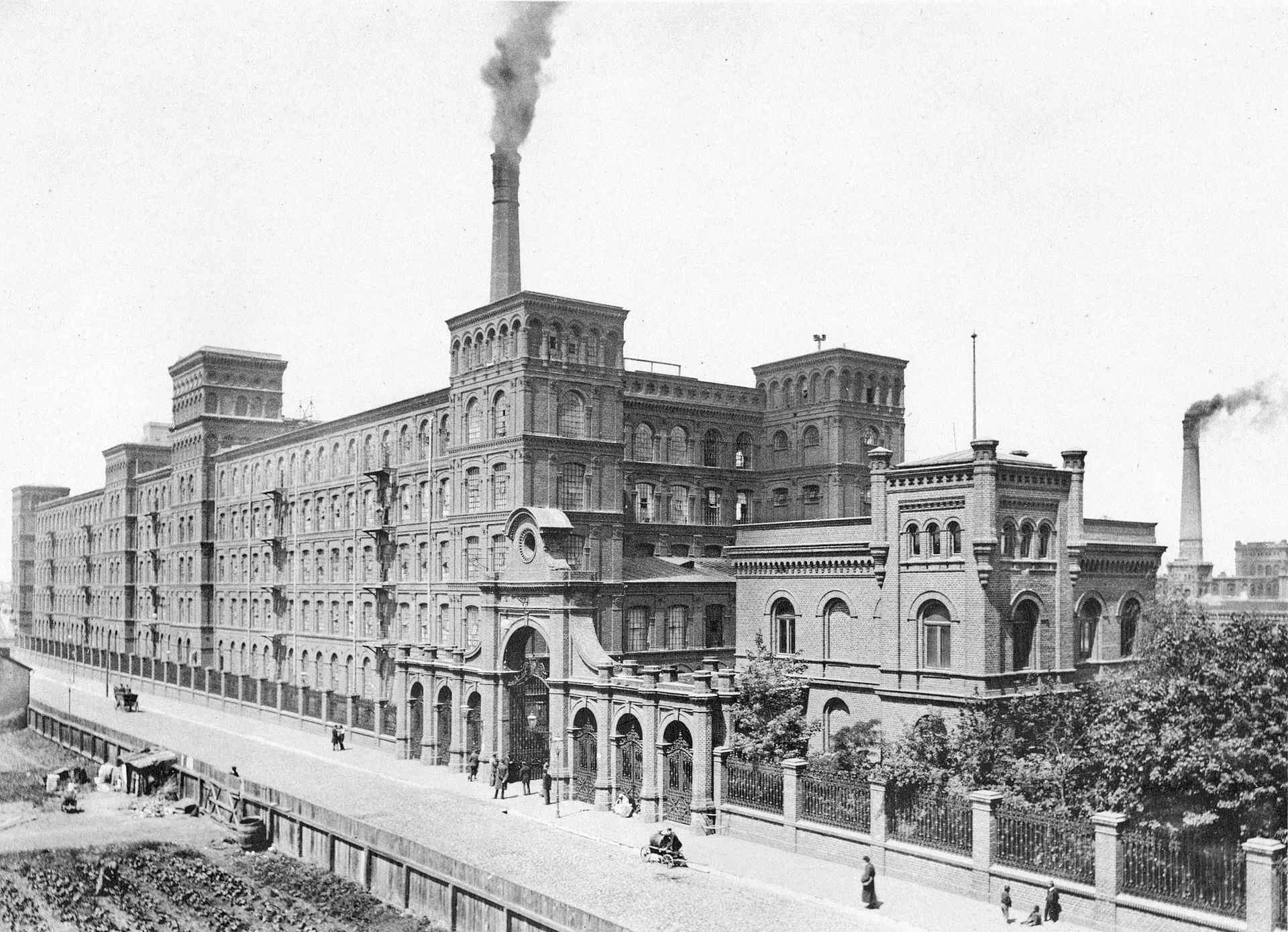

The red-brick factory was once the centrepiece of Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznański’s industrial empire in Łódź. But the 19th-century mill that once wove, bleached and spun cotton has now been refilled with the finished products strewn across some 260 shops.

Izrael Poznański factory in Łódź, c. 1985 (source: Bronisław Wilkoszewski/Wikimedia Commons, under public domain)

In 2003, the former factory was turned into a 270,000-square-metre shopping mall, which also includes 60 restaurants, a culture centre and a hotel. The project was the biggest revitalisation to date in Poland at the time.

In 2019 the neighbouring city of Pabianice also unveiled its own smaller mall of 40 shops, Tkalnia (The Weavery), in the same industrial spirit.

The Manufaktura shopping centre in the former factory (source: jaime.silva/Flickr, under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Other shopping malls have also sprung up in revitalised factories. Opened last year, the upmarket complex in the Powiśle Power Plant in Warsaw has been conceived so as to preserve every brick and button of its industrial past.

Shoppers shuffle down elevated pavements on either side of the central abyss where coal used to fall from roof silos down to burning furnaces. Corridors are lined with massive switchboards that once controlled the power supply to the capital’s main buildings. Bars in the food hall light up with flickering buttons.

Warsaw’s hip Powiśle neighbourhood becomes cooler yet with a new shopping centre opening up in a former power plant, keeping much of the original bricks and buttons. Scarily empty for now though. pic.twitter.com/lcUjg6dH09

— Maria Wilczek (@mariawilczek) May 27, 2020

8. Signposting with neons from the 1950s

The well-known neon of a boy riding a zebra recently returned to the roof of Wedel’s chocolate shop in central Warsaw. It was first put up in the 1950s, when neon signage was all the rage.

#TegoDnia w 1945 r. w #Warszawa rozbłysnął pierwszy powojenny neon.💡 Pojawił się przy ul. Zamoyskiego na budynku fabryki Wedla. 🍫 Dziś przy ul. Szpitalnej możemy podziwiać neon inspirowany plakatem Leonetto Cappiello z 1926 r., przygotowanym na zlecenie Jana Wedla. pic.twitter.com/lkGgZPuJOp

— Warszawa (@warszawa) November 13, 2018

In communist-era Poland, neons were a symbol of urban renewal, splashing colour across the grey facades of new residential flats and administrative buildings.

The communist bloc’s “neonisation” was a centrally planned effort. Urban architects set top-down neon quotas for boulevards and districts. Yet then came the energy shortages of the 1970s and the plug had to be eventually pulled on the ambitious signage plans.

Another pretty Warsaw neon photograph, probably from the late 1960s pic.twitter.com/g3WNY3kE2f

— Christopher Lash (@rightbankwarsaw) January 5, 2016

Now Polish neons are making a comeback as businesses restore their glowing facades and artists renovate scraps of tubing based on archival drawings or new designs.

A museum dedicated to documenting and preserving communist-era neons has also operated in Warsaw since 2012. Itself located in a revitalised former factory, it attracted 100,000 visitors a year before the pandemic.

Warsaw Neon Museum (source: Tomasz Filipek/Unsplash)

Warsaw Neon Museum (source: Ralf Peter Reimann/Flickr, under CC BY-SA 2.0)

Former Soho Factory now housing Warsaw Neon Museum (Mariusz Cieszewski/MFA, under CC BY-NC 2.0)

Main image credit: Nocny Market/Facebook

Maria Wilczek is deputy editor of Notes from Poland. She is a regular writer for The Times, The Economist and Al Jazeera English, and has also featured in Foreign Policy, Politico Europe, The Spectator and Gazeta Wyborcza.