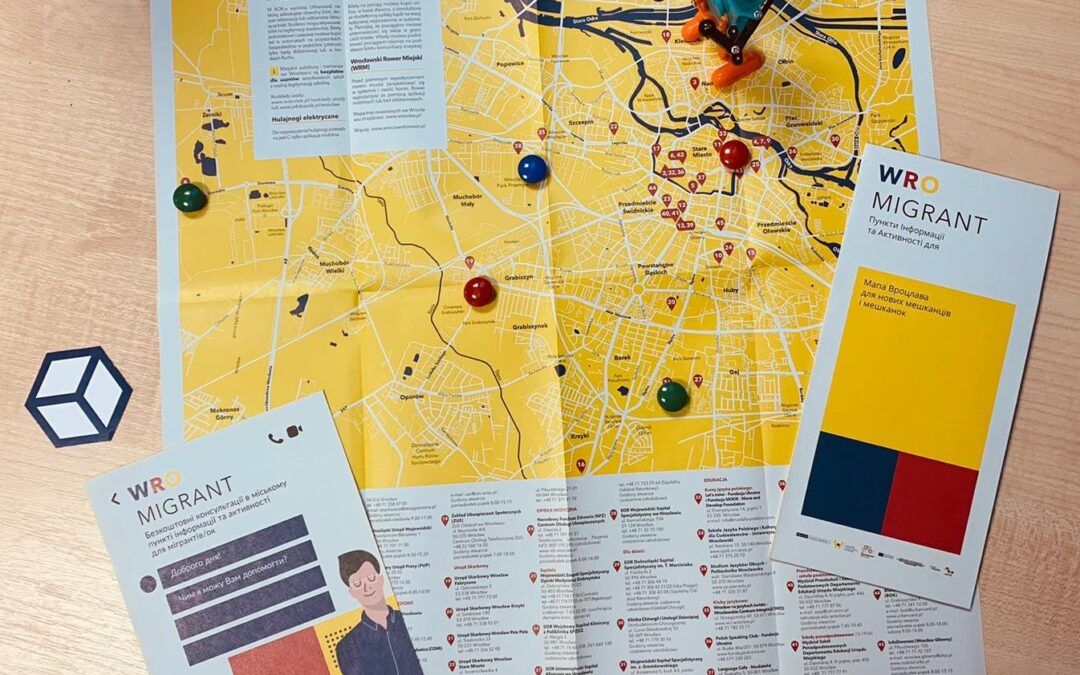

The city of Wrocław has created a map and information pack designed to help new arrivals to integrate.

Created by the Wrocław Centre for Social Development (WCRS), which is a unit of the city’s municipal authorities, the “WroMigrant” map includes details of public offices, medical facilities and NGOs. It also contains information on how foreigners can legalise their stay, get access to education and use public transport.

The information pack – which is available in Polish, English, Ukrainian, Russian and Belarusian – is available online and can be picked up in paper form at various municipal institutions, NGOs and schools (listed here).

“It was a response to an increase in migration to Wrocław and the needs of people with experience of migration,” Albert Miściorak of WCRS’s Intercultural Dialogue Team told the Polish Press Agency (PAP). “The map is intended to help people from other countries who are taking their first steps in the city.”

Poland has in recent years experienced levels of immigration that are unprecedented in its history and among the highest in the European Union. For the last three years, the country has issued more first residence permits to immigrants from outside the EU than any other member state.

The government estimated that, at the end of 2019, there were around two million immigrants living in Poland, making up around 5% of the country’s population. The majority – around 64% – are from neighbouring Ukraine, with the next largest groups being Belarusians and Germans.

Like other large Polish cities, Wrocław has been impacted by this wave of migration. In 2017, municipal authorities estimated that Ukrainians – who numbered 64,000 – constituted 10% of the city’s population. There are now estimated to be 100,000 of them living in Wrocław, reports PAP.

The city, whose mayor, Jacek Sutryk, is associated with Poland’s main centrist national opposition, has taken various steps to support and integrate new arrivals. Last year, Wrocław also became the first Polish city to join the European Coalition of Cities Against Racism. “Openness and diversity are a strength,” said Sutryk.

Many challenges still remains, however, notes Miściorak of WCRS. Although the municipal authorities have tried to streamline the process for foreigners to legalise their stay, “the procedure is still very lengthy, [and can] even take several years”, he told Gazeta Wyborcza.

Miściorak also notes that they have created special preparatory classes for the children of immigrants, to help them learn Polish alongside the school curriculum. The city likewise funds NGOs who provide Polish language classes to adult immigrants, and training in intercultural competence to city employees.

The pandemic has also created particular challenges for immigrants, notes Miściorak. WCRS has sought to translate information on restrictions into various languages. It also provides free consultations by phone, email or instant messaging, reports PAP.

Other Polish cities have taken similar steps. In 2016, Gdańsk’s then mayor, Paweł Adamowicz, appointed an “immigrant council” made up of 12 foreign inhabitants of the city to advice the municipal authorities.

In 2017, Kraków created a special school course for the children of immigrants – as well as those of Polish emigrants returning from abroad – to help them integrate.

Warsaw's mayor has give a free travel pass and Polish lessons to a Belarusian immigrant who pushed a bus after it got stuck in the snow.

A video of the incident, during which a TV reporter joins the man in pushing the bus, went viral in Poland this week https://t.co/DsDItd2BqJ

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 13, 2021

Main image credit: WCRS (press materials)

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.