Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Nicholas Boston

Five years ago, I wrote a series of articles for various outlets, including Notes from Poland, about August Agboola Browne, a Nigerian-born jazz musician and actor who made Poland his home between 1922 and 1956 and is believed to have fought in the Warsaw Uprising of 1944 – for which he has been celebrated as a hero in his adopted homeland.

But, in a subsequently unearthed file, Browne claims that he was imprisoned in concentration camps in German-occupied Poland for most of World War Two, including at the time of the uprising.

Yet, despite the apparent inconsistencies, these files and others from the archives help to paint a clearer picture of Browne’s life before, during and after the war.

It all started in 2008 when an archivist at the Warsaw Rising Museum discovered application forms Browne filed in 1949 for membership in the veterans’ association ZBoWiD (Society of Fighters for Freedom and Democracy), claiming he had been an insurgent in the Warsaw Uprising under the codename “Ali”.

Although it was long understood that a few foreign nationals had taken part in the Polish resistance, a black African participant was novel. Over the ensuing decade, Browne’s celebrity swelled. He became, as I wrote for Notes from Poland, a symbol of national pride across the political spectrum.

A Nigerian migrant to Poland called August Agboola Browne participated in the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. His story is remembered in the Polish capital today.

Browne was a jazz percussionist who joined the resistance under the code name “Ali”. https://t.co/rRxr9QELuW

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) July 31, 2020

But no record of his involvement in the Warsaw Uprising was to be found.

“Having spent a few years with archives of this organisation, I would not trust any of the personal declarations collected by ZBoWiD (or its preceding associations) at face value without very careful additional contextual research, considering other primary sources,” said Dr Joanna Wawrzyniak, director of the Center for Research on Social Memory at the University of Warsaw.

I searched for Browne in the archives of countries he was thought to have resided in before and after Poland, and found a number of surprises. I was able to trace him from his parents’ home address in Lagos in the 1910s, to an apartment in the Montmartre district of Paris in 1920, to Antwerp later in the 20s, to the Poland years, then to his final place of residence, in London, before his death in 1976. An odyssey of self-invention.

Nazi persecution claim

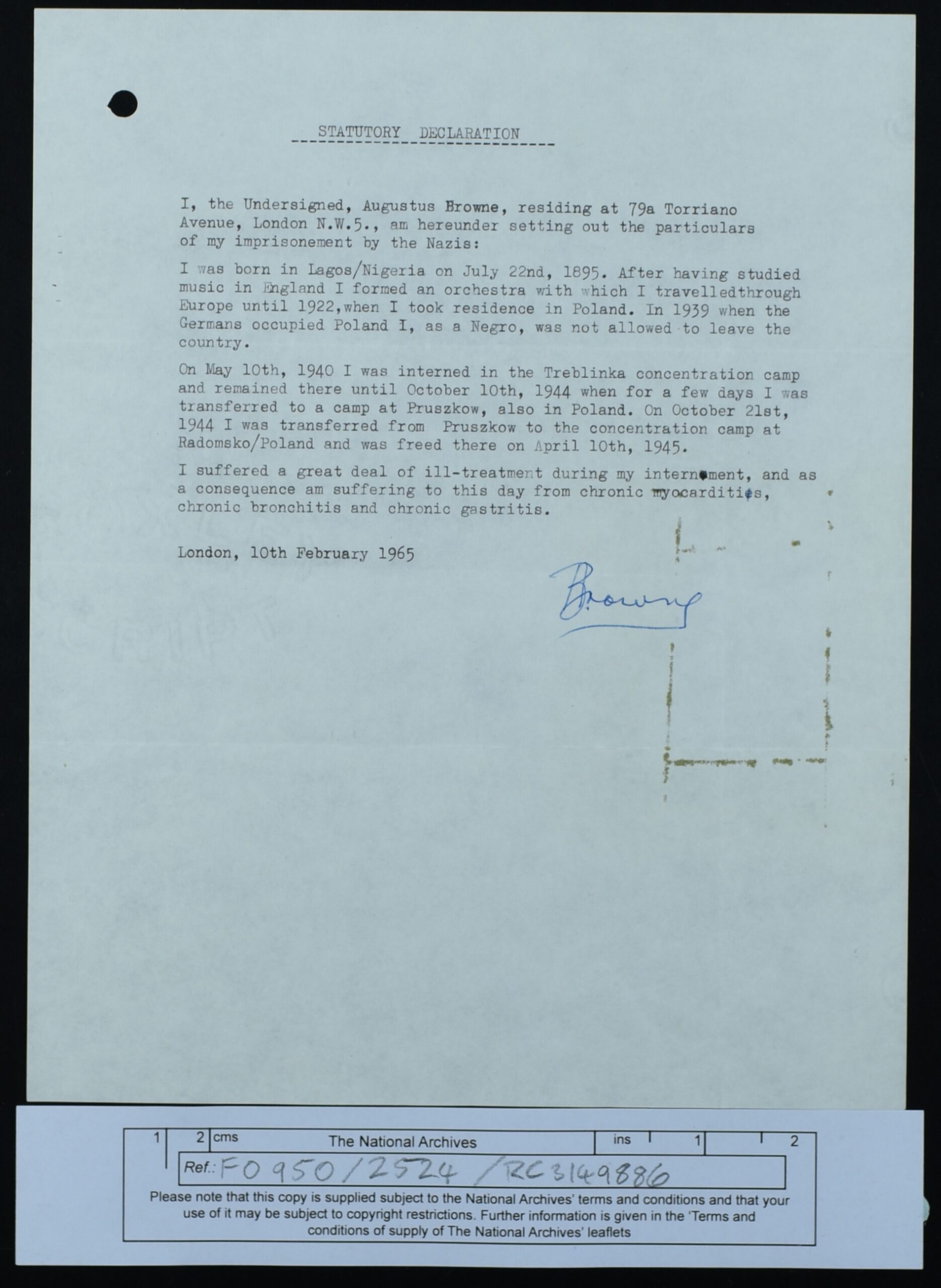

In the UK National Archives, I found a large file titled “Nazi persecution claim: Mr Augustus Browne”. It comprises over 60 separate documents, letters, memos, medical examination reports, certified declarations and identification cards, all to process an “application for registration as a British victim of Nazi persecution” that Browne filed in 1965.

“I, the undersigned, Augustus Browne,” reads his declaration, “am hereunder setting out the particulars of my imprisonment by the Nazis…In 1939 when the Germans occupied Poland I, as a Negro, was not allowed to leave the country. On May 10th, 1940 I was interned in the Treblinka concentration camp and remained there until October 10th, 1944 when for a few days I was transferred to a camp at Pruszkow, also in Poland. On October 21st, 1944 I was transferred from Pruszkow to the concentration camp at Radomsko/Poland and was freed there on April 10th, 1945.”

Browne’s signed declaration of internment in Treblinka and other “concentration camps” (courtesy of UK National Archives – no reuse)

Taken at face value, this would completely exclude the possibility that Browne fought in the Warsaw Uprising, which took place from August to October 1944. But experts of the period whom I consulted roundly dismissed the entire scenario outlined by Browne in his British claim.

“I have read very many testimonies from Treblinka I and II” – like its sinister sibling, Auschwitz, the camp had two sites, one for forced labour and the other extermination, primarily of Jews – “and there is no chance of an African having been detained there,” said Professor Jan Grabowski of the University of Ottawa, Canada, a world-renowned historian of the Holocaust and its aftermath, particularly in Poland. “We would have many, many testimonies about it.”

The dates Browne gave for his period in detention were also incongruous with Treblinka’s timeline of operation, a fact evident at the time from data collected by the International Tracing Service (now called the Arolsen Archives), the bureau set up in Germany to trace victims of Nazi persecution and provide intelligence about their fates, which upon consultation by British officials on Browne’s case found no record of his internment.

A mass grave has been discovered beneath a car park at the site of the former German Nazi camp Treblinka https://t.co/mboyuCiEjn

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) November 16, 2019

Browne did actually submit an eyewitness testimony, from a Mrs Barbara Filipowska of Warsaw, testifying to his presence at Treblinka. But no copy of the document remains in the file.

Curiously, Browne originally procured Filipowska’s declaration in 1958, two years after he had left Poland and a good seven before the Nazi persecution claim was even a thought. At the same time, the claim file shows, he acquired a “medical certificate issued by Dr Stanisław Ogłoza of Warsaw on March 24th, 1958,” (also absent from the file). For what earlier purpose might these two related documents have been used?

“I would say that Browne wanted to get some compensation, and who can blame him?” Professor Grabowski said. “Probably he went through different circles of hell for which compensation was more than necessary. Many people acted along the same lines.”

The Anglo-German Compensation Agreement of 1964

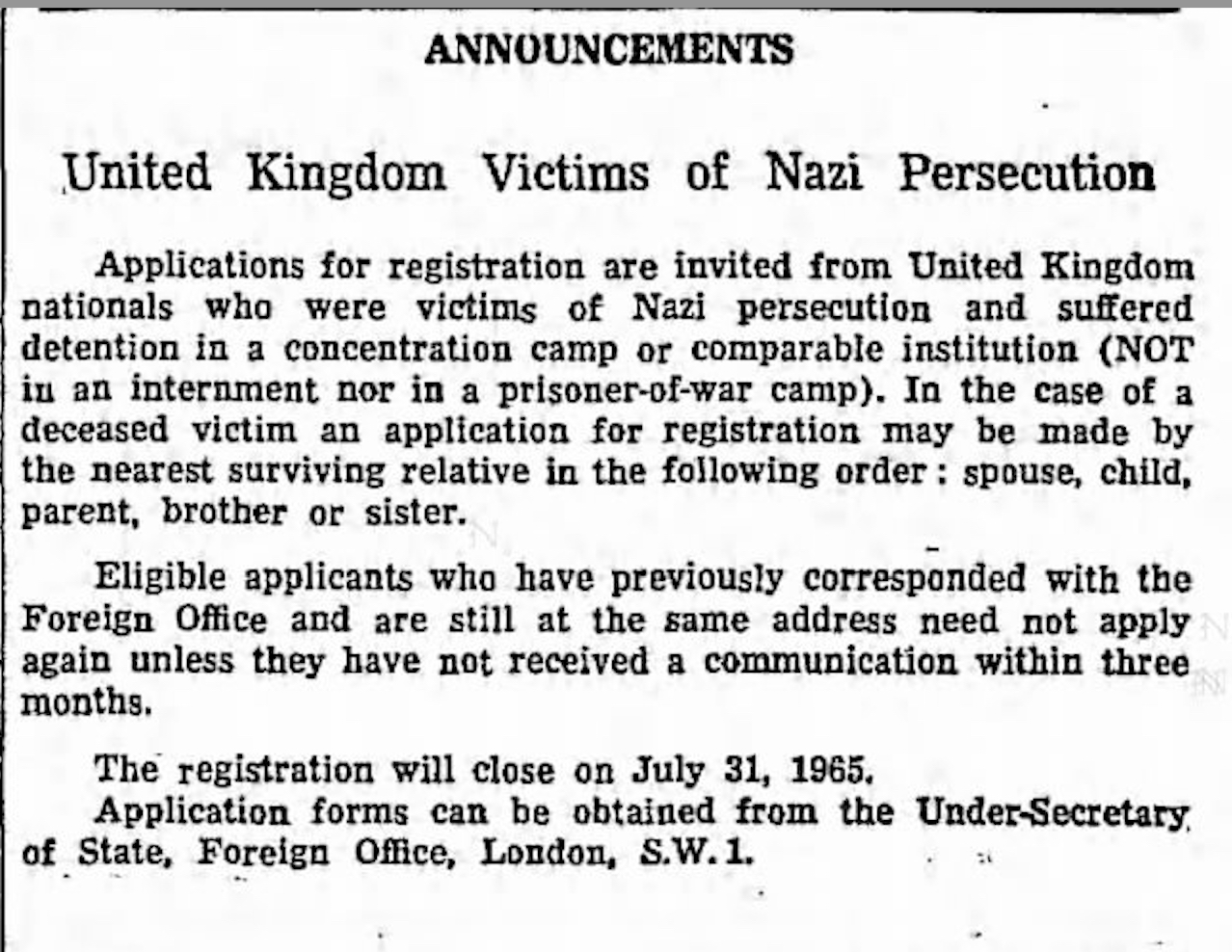

In June, 1964, following a decade-long negotiation, West Germany agreed to pay the United Kingdom £1 million to compensate UK nationals persecuted under Nazism. The programme was advertised nationwide, restricting eligibility to individuals who “suffered detention in a concentration camp or comparable institution (not in an internment nor in a prisoner-of-war camp)”.

Advertisement published in British newspapers such as The Guardian

Of the over 4,000 applications received, roughly a quarter were approved, Browne’s among them. Despite weaknesses in the claim, he was compensated in the amount of £2,385, an estimated value of £59,016 today.

Browne was 70 years of age and in declining health (he would live only 11 more years). According to his daughter Tatiana, now 66, Browne’s main source of income as a session musician “dried up”, leaving only private piano lessons he gave in their home. On a windfall of cash, he would have subsisted, not splurged.

When the compensation scheme was wrapped up in 1966, all files were delivered to the National Archives and sealed for 50 years. They began to be declassified in batches in 2016, by which time in Poland “Ali” had been made a hero.

Two claims forms, one story

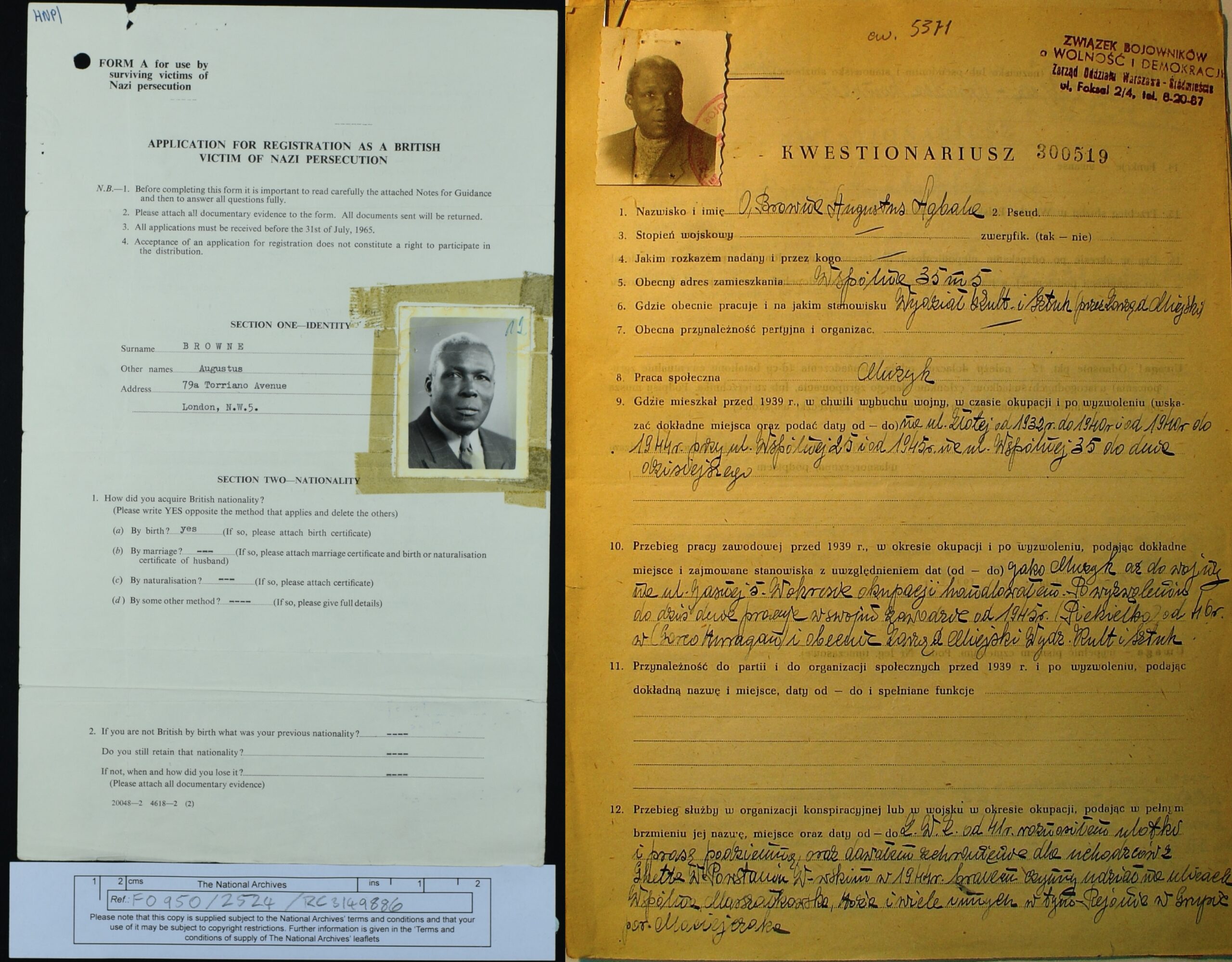

Browne’s compensation application form bears a generic resemblance to his ZBoWiD application form. No discrepancies exist between the identifying information (date and place of birth, etc.) he provided on them. Affixed to both is Browne’s photograph: a handsome, healthy-looking, well-dressed man with a full head of hair (which in the later image has turned completely grey).

Both applications – one asserting Browne served in the Polish resistance and the other that he was a camp prisoner – are standalone claims that lack official evidence.

Left: front page of Browne’s application for compensation as a British victim of Nazi persecution, 1965 (courtesy of UK National Archives – no reuse). Right: front page of Browne’s ZBoWiD application, 1949 (courtesy of Warsaw Rising Museum)

But instead of contradicting each other, a comparison of the two helps fill in the gaps of Browne’s undeniably unique life journey.

None of the documents Browne supplied in support of his claim connected him to Treblinka. And the camps for which he did provide sound proof of his presence, Pruszków and Radomsko, he misdefined as concentration, not transit, camps.

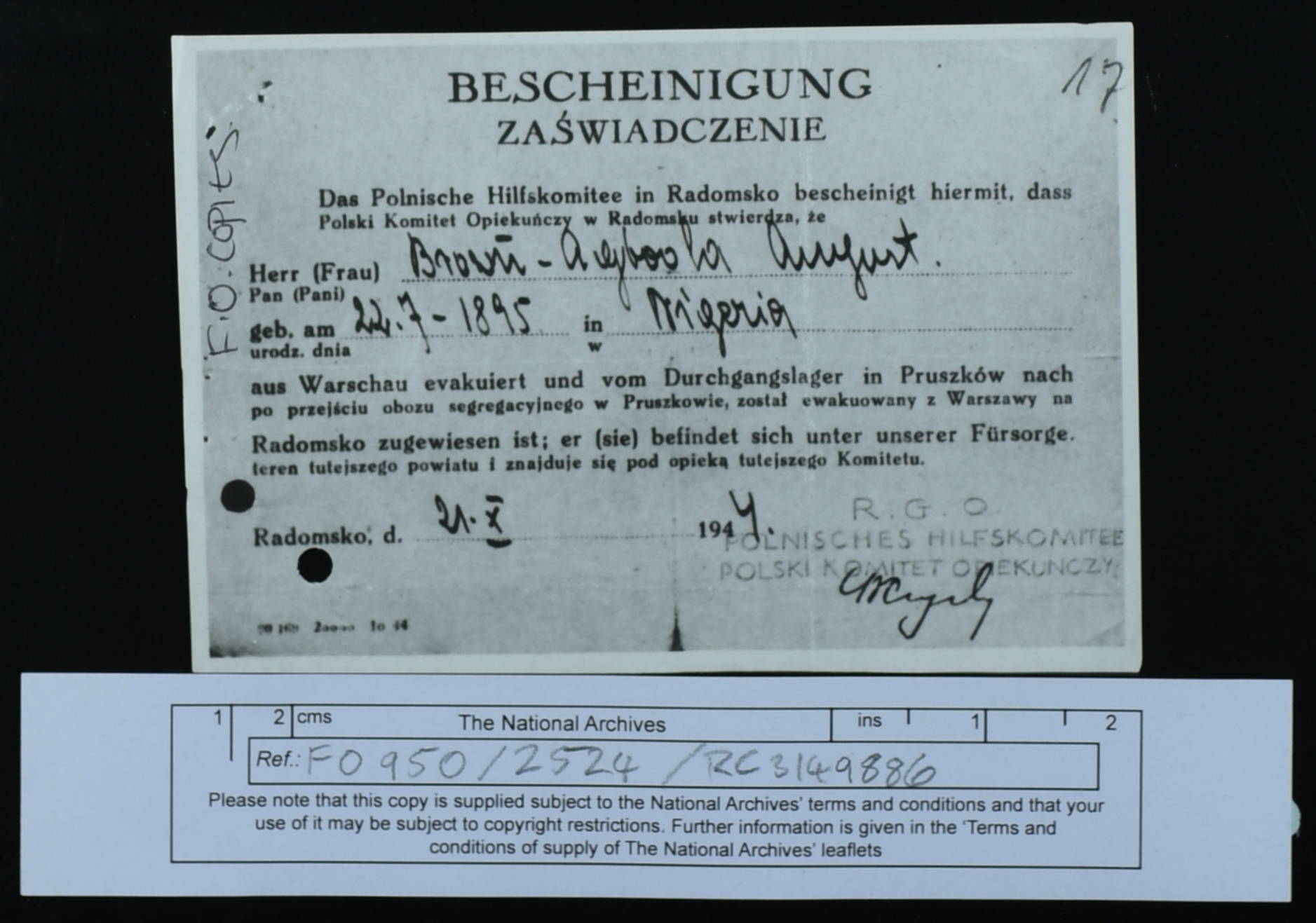

The record of his arrival in the latter is a small card stating in German and Polish, “The Polish Relief Committee in Radomsko hereby certifies that Brown-Agboola August, born 22.7.1895 in Nigeria, was evacuated from Warsaw and transferred from the transit camp in Pruszków to Radomsko; he is under our care. October 21, 1944.”

Certificate issued by the Polish Relief Committee at Radomsko on 21 October 1944 (courtesy of UK National Archives – no reuse)

“This certificate is a very standard document given out to civilians deported from Warsaw after the uprising,” Professor Grabowski said.

Upon the Home Army’s capitulation on 2 October 1944, bringing a close to the Warsaw Uprising, all civilians were expelled from the city. Varsovians in the hundreds of thousands were herded on foot to a transit camp, Dulag 121, in the nearby town of Pruszków. After a short stay there, they were sent on to other locations, like Radomsko.

At the time persecution claims like Browne’s were being assessed in the UK, the cataloguing of Nazi carceral and genocidal operations was still in progress. Even the ITS, responding to a query about the places Browne named, wrote, “In regard to Radomsko, we can only ascertain that a prison was there”.

Few of the British assessors held expert knowledge of Poland and the other formerly Nazi-occupied countries where atrocities were carried out, so they sometimes struggled to make sense of the documentation put before them.

One handwritten memo in Browne’s file reads, “The Radomsko certificate was issued in 1944 (October) but I am really not sure whether the Germans were still there. I rather think they were, because the card is in German as well as Polish but perhaps Radomsko was in an area where many Germans lived anyway? Do we know where Radomsko is?”

Browne had to submit his medical records as well as undergo an examination by a state-appointed physician. Both reported chronic health conditions, confirming Browne’s declaration that “I suffered a great deal of ill-treatment during my internment”.

Identification card

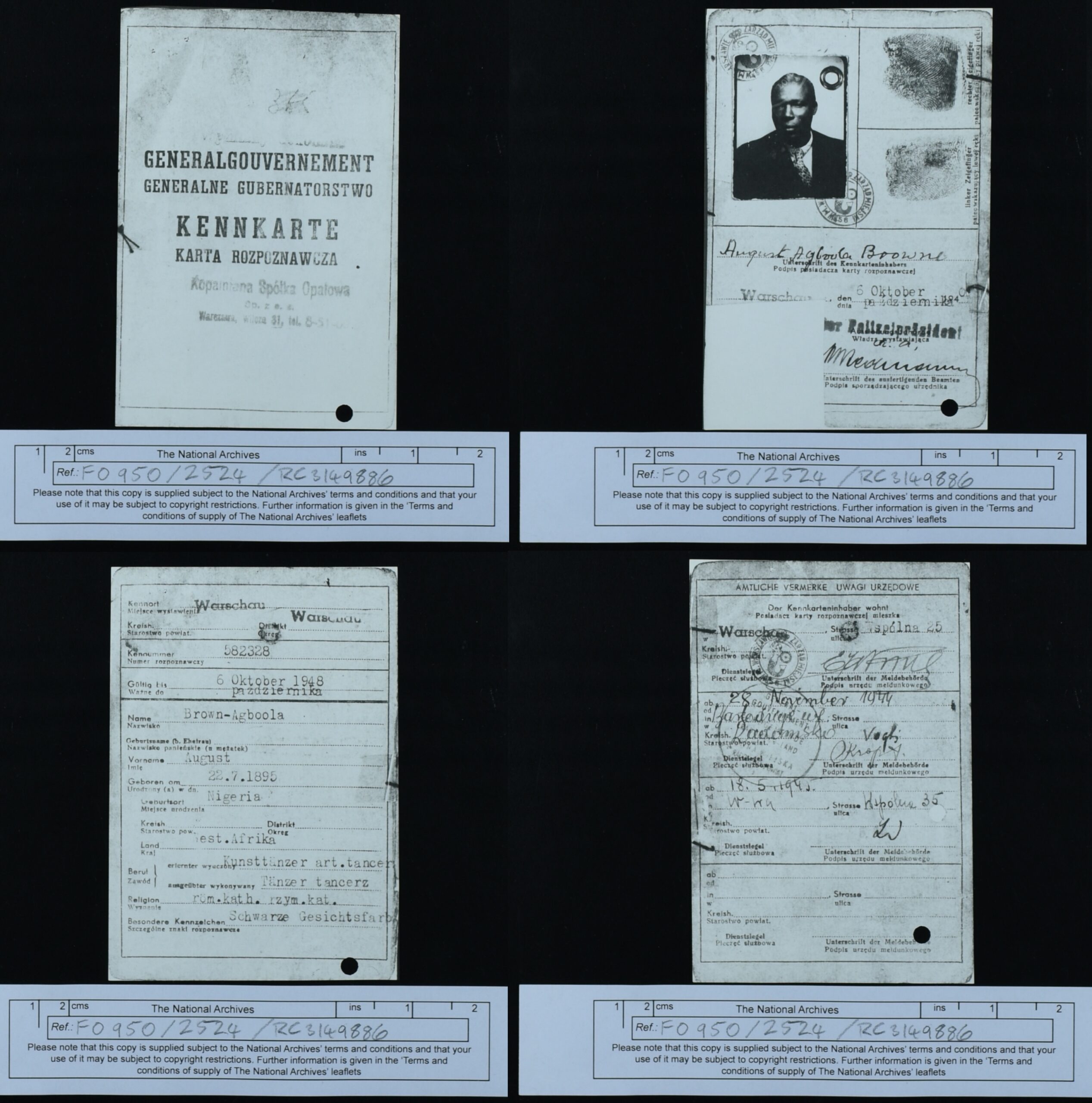

One object in the file that is of special significance, not only to Browne’s past, but Second World War history in general, is his Kennkarte, the six-panelled identification card all civilians were required to carry throughout German-occupied Europe.

The card had a passport-sized photograph of its holder, his or her fingerprints, home address, religion, date and place of issue, and expiration date. There was a line for “special distinguishing marks”, which on Browne’s card states “Schwarze Gesichtsfarb” – black complexion.

Four panels of Browne’s Kennkarte (courtesy of UK National Archives – no reuse)

I consulted the institutions with the largest holdings of such cards, and it appears to be the only example of a Kennkarte issued to a black or other non-white person in Nazi-occupied Poland known to exist in any public archive.

“In our collection we only have documents of Poles, Ukrainians and Jews,” said Dr Wojciech Łukaszun, head of the department of collections and digitisation at the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk. “I have no knowledge of any other persons holding German documents in the Generalgouvernement [occupied territory] such as August Agboola Browne.”

The Kennkarten were colour-coded and stamped according to the holder’s race: grey for Poles; yellow for Jews (with a big, black “J” on the front) and Roma; blue for Russians, Ukrainians and other Slavs. Browne did not fit into any of these categories, but he was issued a blue card. The question is, by whom?

Card forgery was commonplace, particularly for Jews who changed their names and religion or assumed an entirely false identity to evade omnipresent danger.

On Browne’s card, the date of issue is 6 October 1940, which is extremely rare, as issuance of Kennkarten in occupied Poland did not become mandatory until June 1941. If the card was the work of a forger, such a glaring inaccuracy would have been a dead giveaway, but it bears stamps and dates up to 18 May 1945, suggesting Browne used it unimpeded throughout the war.

“This is an interesting case,” said Dr Sebastian Piątkowski of the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN), an expert on Third Reich documentation, clarifying that “Kennkarten were introduced in Poland by Hans Frank‘s [the governor-general’s] decree of 26 October 1939, from which point it was possible to obtain this document, but the Germans tolerated the use of Polish ID cards up to 1941 when the Kennkarte was introduced compulsorily, and from then on, everyone over the age of 15 was required to have one.”

Dr Piątkowski estimates that Browne’s haste in acquiring his Kennkarte had to do with not holding Polish citizenship, hence feeling vulnerable, especially since the passport he did hold, of Great Britain, was the enemy’s. It is extraordinary that Browne felt such a strong pull to Poland that he chose to remain after not only the outbreak of war but his categorisation as enemy by nationality and Untermensch, subhuman, by race.

Browne’s concentration camp story is most certainly made up. The supporting documents themselves belie the claim. But the gem among them is his Kennkarte. It proves his presence, even giving his exact location – 25 and 35 Wspólna Street. Above all else, it proves his extraordinary ability to survive in the most devastating episode in the formation of modern Poland. His hypervisibility might, counterintuitively, have been his strength, an unthreatening, incapable Untermensch.

As trained historians, all of the experts I spoke with declined to dismiss Browne’s participation in the Warsaw Uprising based on existing documentation alone.

“I will give you the example of my father, who was 17 at the time,” Professor Grabowski told me. “His greatest pride was that he was also fighting in the Warsaw Uprising, as a Jew who emerged from hiding. But, in reality, he was not a member of the Home Army because he was basically helping. He was digging trenches, he was running with the Molotov cocktails, but he never was officially enrolled, so to say.”

“You know, the city is burning around you, and you see people fighting who are close to you, so, you join. I mean, from time to time… Browne could have assisted. He could have helped bringing food or digging trenches or simply making himself useful.”

A wily old bird

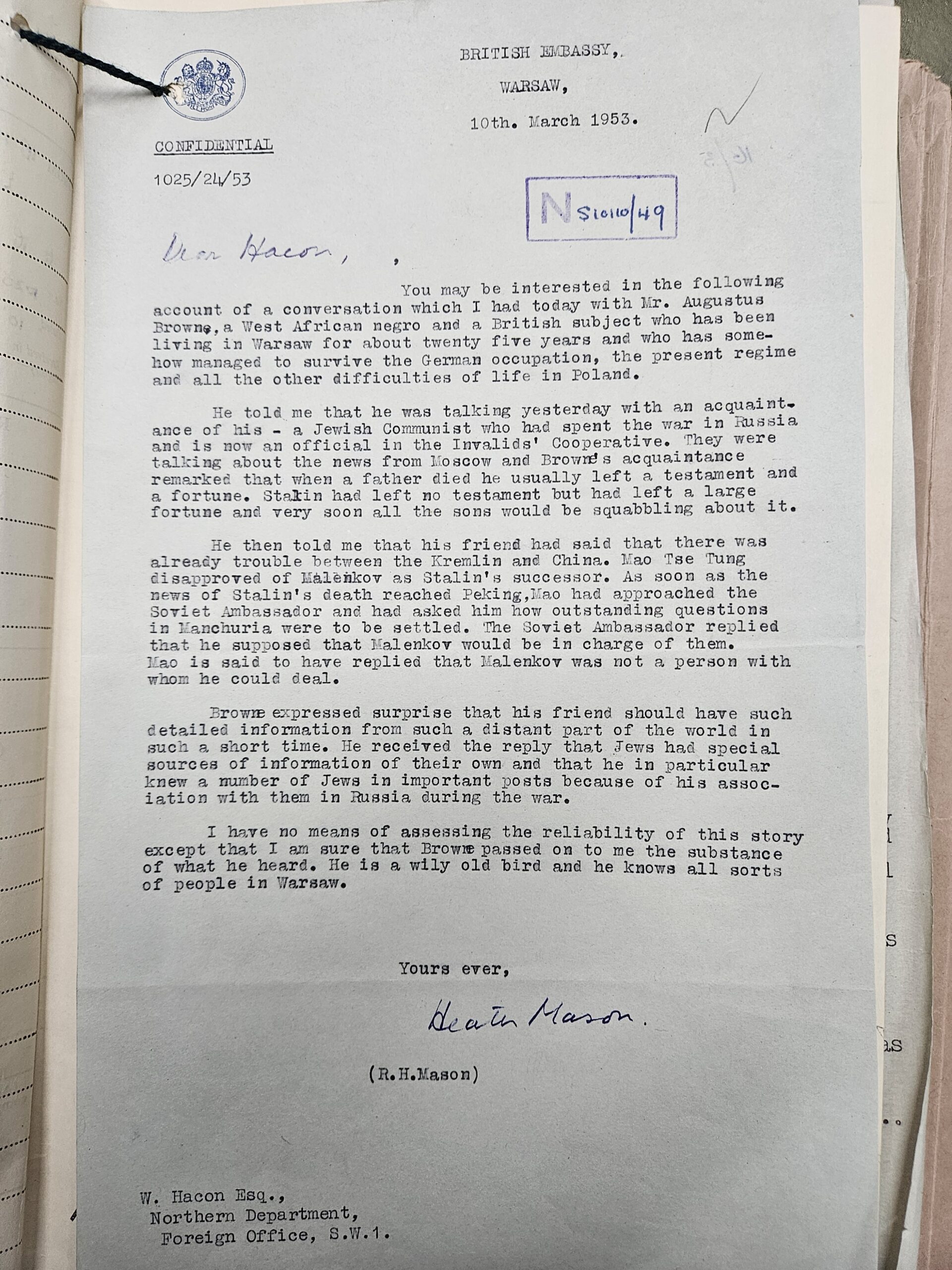

Browne had contacts in many different milieus, including government, even under the postwar communist regime. So much so that a higher-up in the British embassy in Warsaw described him as a “wily old bird” who “knows all sorts of people in Warsaw”.

In a confidential letter to a colleague in London dated 10 March 1953, Robert Heath Mason, then first secretary of the British embassy in Warsaw, recounted “a conversation which I had today with Mr. Augustus Browne, a West African negro and a British subject who has been living in Warsaw for about twenty five years and who has somehow managed to survive the German occupation, the present regime and all the other difficulties of life in Poland”.

Letter from the First Secretary of the British Embassy in Warsaw about Browne, 1953 (courtesy of UK National Archives – no reuse)

Mason proceeded to convey background information Browne had passed on to him concerning the Soviet politician Georgy Malenkov’s appointment as premier of the USSR upon the death of Joseph Stalin five days earlier. Browne told Mason that the Chinese leader Mao Zedong disapproved of Malenkov, auguring discord between the two nations.

This account adds to others of Browne’s charisma and profound aptitude for persuasion.

“Dad had a real quick wit and a real charm about him,” Tatiana once told me. “When he was in company with other people, there was just this energy. People were drawn to him.”

Paternal echoes

Besides Tatiana, Browne fathered Kraków-born sons Ryszard Stefan Browne (1928–2019) and Aleksander Browne (1929/30–2012) with first wife Zofia née Pykówna (or Pyk) (1909–1999), and Ciechanów-born Beata Marta Brown-Łuczak (1952–2021), with a partner between his two marriages.

The siblings grew up as strangers. Tatiana did not even know she had a half-sister until Beata, a lifelong resident of Poland, contacted her amid the first “flurry of interest” in their father in the Polish media. The half-brothers she knew existed but never met, despite all living in London.

In spite of all of Browne’s children except Tatiana not growing up around him, their attributes and undertakings eerily echoed their father’s.

Aleksander became an actor like his father, appearing on stage and screen. In 1963, he was the second black character introduced on the classic British TV serial, “Coronation Street,” cast in a recurring role as a doctor.

A review of one of his plays in 1958 noted, “Aleksander Browne, a coloured actor from Poland, was a young boy living in Cracow when the Germans marched in and the Gestapo sent him, his mother and his brother off to a concentration camp in an open lorry in mid-winter”. The commentary stops short at explaining that the family’s flight to safety in England happened on the strength of his father’s British nationality.

Beata followed in her father’s insurgent footsteps, mythic or not. She was an active member of the Solidarity union from 1982 to 1987, distributing underground periodicals, just as her father claimed he did during the Warsaw Uprising. For her acts, Beata received the Cross of Freedom and Solidarity, Poland’s highest civilian honour, in 2018.

As the Solidarity trade union turns 40, @Jac_Hayden explains how the diverse mass movement that toppled communism has since 1989 morphed into an ally of today’s conservative government, supporting its campaign against "LGBT ideology" and liberal values https://t.co/zpPeJgblsf

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) August 28, 2020

Browne’s eldest, Ryszard, who went by “Dick”, was a Royal Air Force pilot before joining International Computers Limited, Britain’s largest computer equipment supplier in the 1970s, where he rose to manager of the Polish branch in Warsaw. August had written in his ZBoWiD application that he traded in electronic equipment during the occupation (he was witnessed doing so by the photographer Andrzej Zborski).

Dick, with his English wife, Jean, enjoyed hosting dinner parties for the staff at their home, recalled a former junior colleague of his, Andrew Piekarski, now 80.

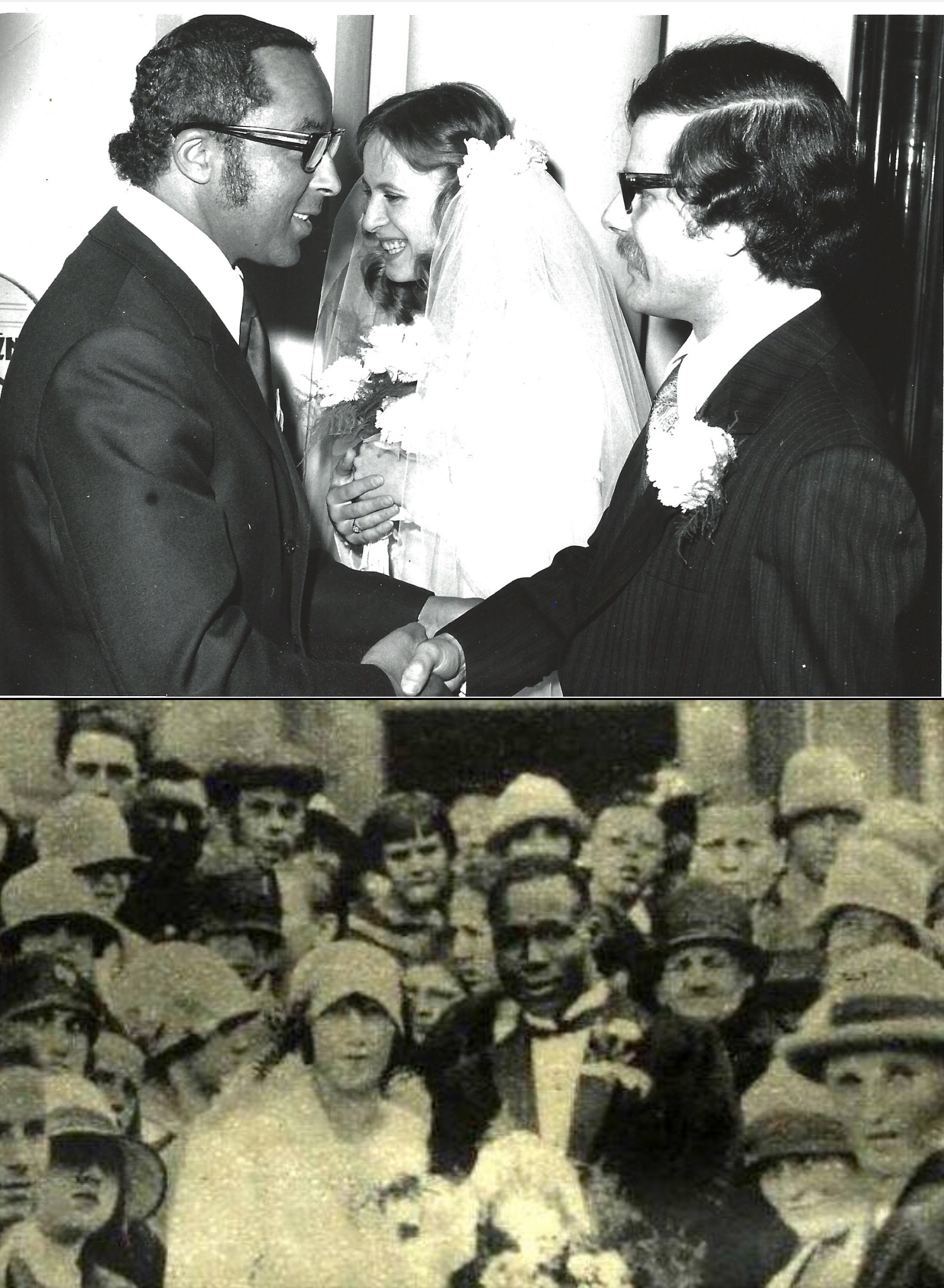

Dick attended Mr Piekarski’s wedding to wife Anna in Warsaw in 1973, and was snapped congratulating the groom with the joyful bride between them.

The photograph brings to mind a photo of Dick’s parents’ wedding party in Kraków in 1927 that was published in a sensationalist periodical printed because the couple was interracial.

Top: Dick Browne congratulating Andrew Piekarski at his wedding to wife Anna, Church of the Visitants, Warsaw, 23 April 1973 (courtesy of Andrew and Anna Piekarski – no reuse). Bottom: Wedding of Browne and Zofia, Church of Saints Peter and Paul, Kraków, 1927 (public domain).

Dick experienced the hypervisibility known to August and responded in similar fashion.

“It happened so many times I would go to a sales meeting and at one point it was time to bring in your sales manager and he would walk in,” Mr Piekarski said. “Dick joked about how jaws would fall when they saw that he was black. We’re talking about a communist Poland in the 1970s that had been fairly isolated from the real world.”

“I hope you will forgive me”

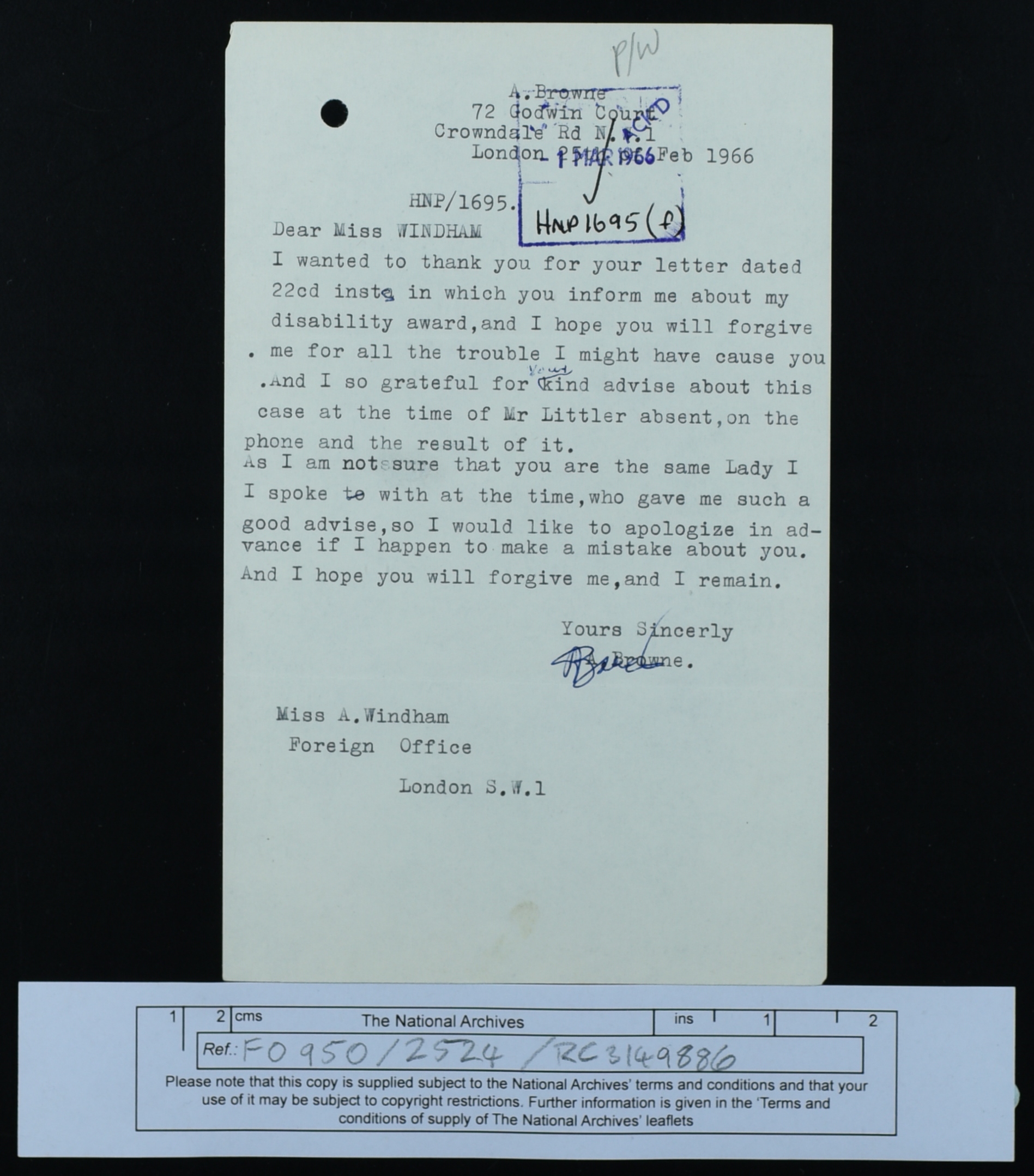

Among the correspondence in Browne’s application for compensation file is a letter he sent to an official handling his case. In it, he wishes to thank her for the good news she had sent him that he would be receiving a lump sum for disability.

Whereas every other letter to which Browne signed his name, in this file and the ZBoWiD one, was prepared by proxy, this note is in Browne’s own words – and apparently his typewriting. The misspellings, grammatical errors and typos are authentic: though fluent in English, Polish was his daily language for over 40 years.

“I hope you will forgive me,” Browne says at the conclusion. “And I remain, Yours sincerly, A. Browne.”

Letter of thanks from Browne to claims officer, 1966 (courtesy of UK National Archives – no reuse)

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Adam Stepien / Agencja Wyborcza.pl