By Daniel Tilles

Ewa Kłobukowska was tipped to be one of the greatest sprinters of her generation after winning Olympic gold aged 18. But just three years later, her career was ended when she became the first athlete banned for failing a sex verification test – one now known to have been inaccurate.

The controversy at the recent Paris Olympics over the eligibility of two boxers, Imane Khelif and Lin Yu-ting, can feel like a very modern debate.

But a remarkably similar situation arose six decades ago around Polish sprinter Ewa Kłobukowska, a figure largely forgotten today but one whose case changed the way gender testing is conducted.

At the Tokyo Olympics of 1964, Kłobukowska – who had turned 18 while travelling to the games – won gold as part of the Polish women’s 4x100m relay team, who set a world record time. In the individual 100m dash, she won bronze.

Kłobukowska (far right) running the final leg of the women’s 4x100m relay final at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, which was won by her Polish team in world record time (credit: unknown author/Wikimedia Commons, under public domain)

A year later, Kłobukowska set an individual world record time in the women’s 100m of 11.1 seconds and, in 1966, she became European 100m champion.

However, at the 1967 European Cup competition in Kyiv, Kłobukowska suddenly and mysteriously disappeared from the event.

At first, it was said she had an injury. But in fact she had been excluded due to failing a gender test – one that is now known to have been unreliable but which ended her career and resulted in private and public humiliation.

“One chromosome too many”

Reports that emerged at the time suggested Kłobukowska had failed a “close-up visual inspection of the genitalia [which] was used to establish eligibility” during the athletics event in Kyiv.

Danuta Straszyńska, a Polish hurdler from the time, later recalled experiencing those “terrible tests” in which athletes were “stripped naked” and “paraded in front of a commission” for assessment.

As a result of Kłobukowska’s “visual inspection”, further investigation was carried out and she then became the first-ever athlete to be disqualified through the Barr body test, a recently introduced prototype chromosome test.

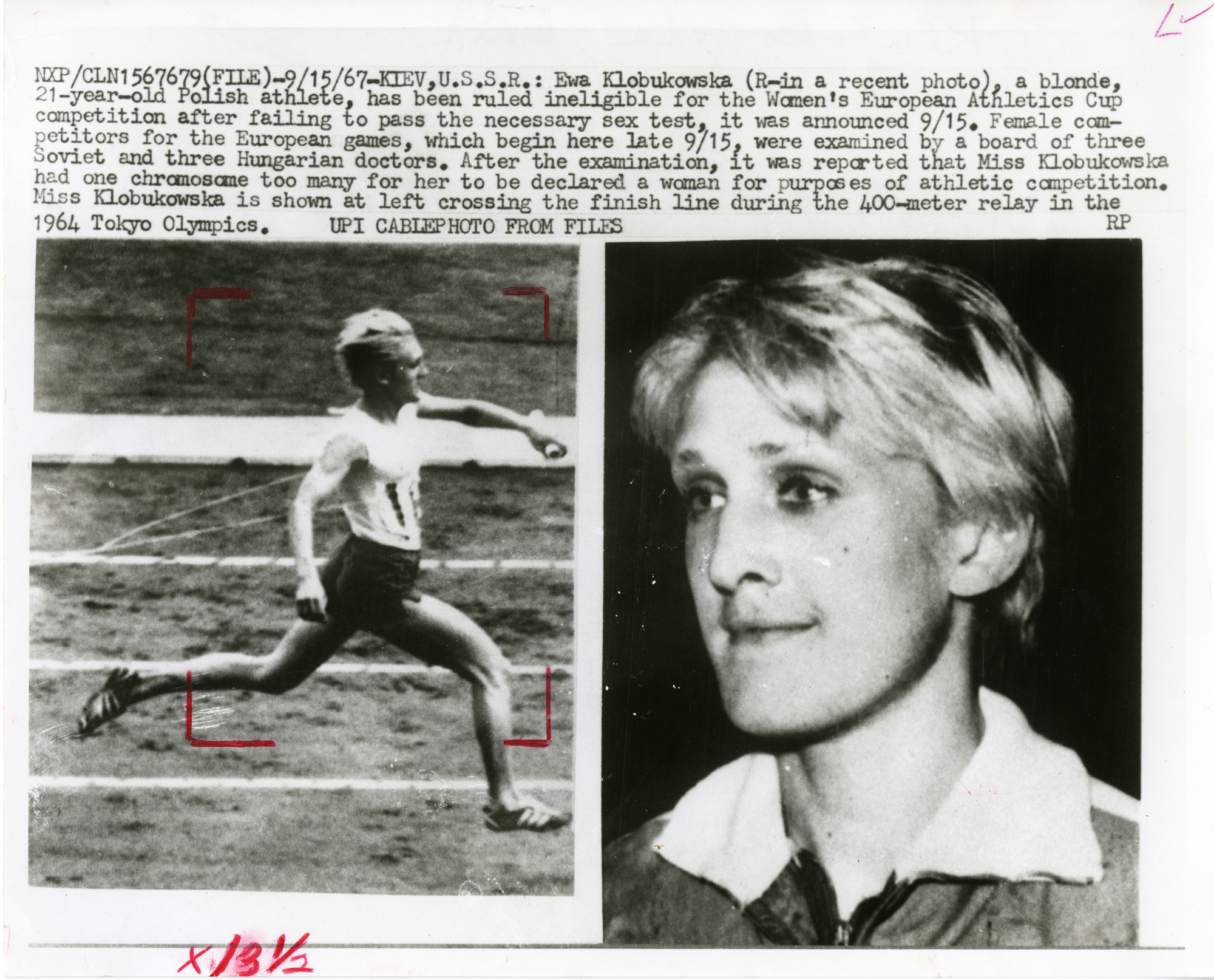

It was publicly announced that the athlete had “failed to pass the necessary sex test” due to having “one chromosome too many for her to be declared a woman for the purposes of athletic competition”.

A contemporary report of Kłobukowska’s ban (credit: Smithsonian Institution, under public domain)

Kłobukowska’s coach, Jan Mulak, later wrote in his autobiography that “it was decided that it would be a departure from the principle of fair play if she were allowed to compete with women”. However, he described the decision as “absurd”.

As a result of failing the test, Kłobukowska was stripped of the world records she had set – both individually and as part of the Polish relay team – and faced public ridicule, with some media reports declaring her to be a man.

However, as doctors Robert Ritchie, John Reynard and Tom Lewis note in their 2008 article, “Intersex and the Olympic Games”, for the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine:

[While] in the eyes of the regulatory bodies, the case of Klobukowska and others justified gender verification and enthusiasm for compulsory testing continued…in reality, the introduction of Barr body analysis created more problems than it solved – confirming or refuting sex purely via a chromosomal test fails to take account of the complexities of sex determination itself.

Kłobukowska herself perfectly highlighted those complexities when, just one year after failing the sex verification test, she became pregnant and gave birth to a child.

Even Murray Barr himself, the Canadian scientist who invented the test, “cautioned against using it as the sole determinant of sex”, note scholars Jörg Krieger, Lindsay Parks Pieper and Ian Ritchie in a 2018 paper on fairness in sport.

Sorry to interrupt your reading. The article continues below.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

However, rather than trying to fight the accusations against her, Kłobukowska decided to withdraw from the sport. After earning a masters degree in economics, she spent the rest of her career working at a firm producing industrial equipment.

In a recent article for the magazine Krytyka Polityczna, Anna Sulińska, author of a book on Polish female Olympic athletes under communism, argued that there was also another factor in the move to ban Kłobukowska.

The Germans and Soviets were frustrated by the success of Poland’s young female sprinters, who they feared would dominate the sport for years to come. They therefore looked for ways to exclude them, and gender testing was the only feasible route, writes Sulińska.

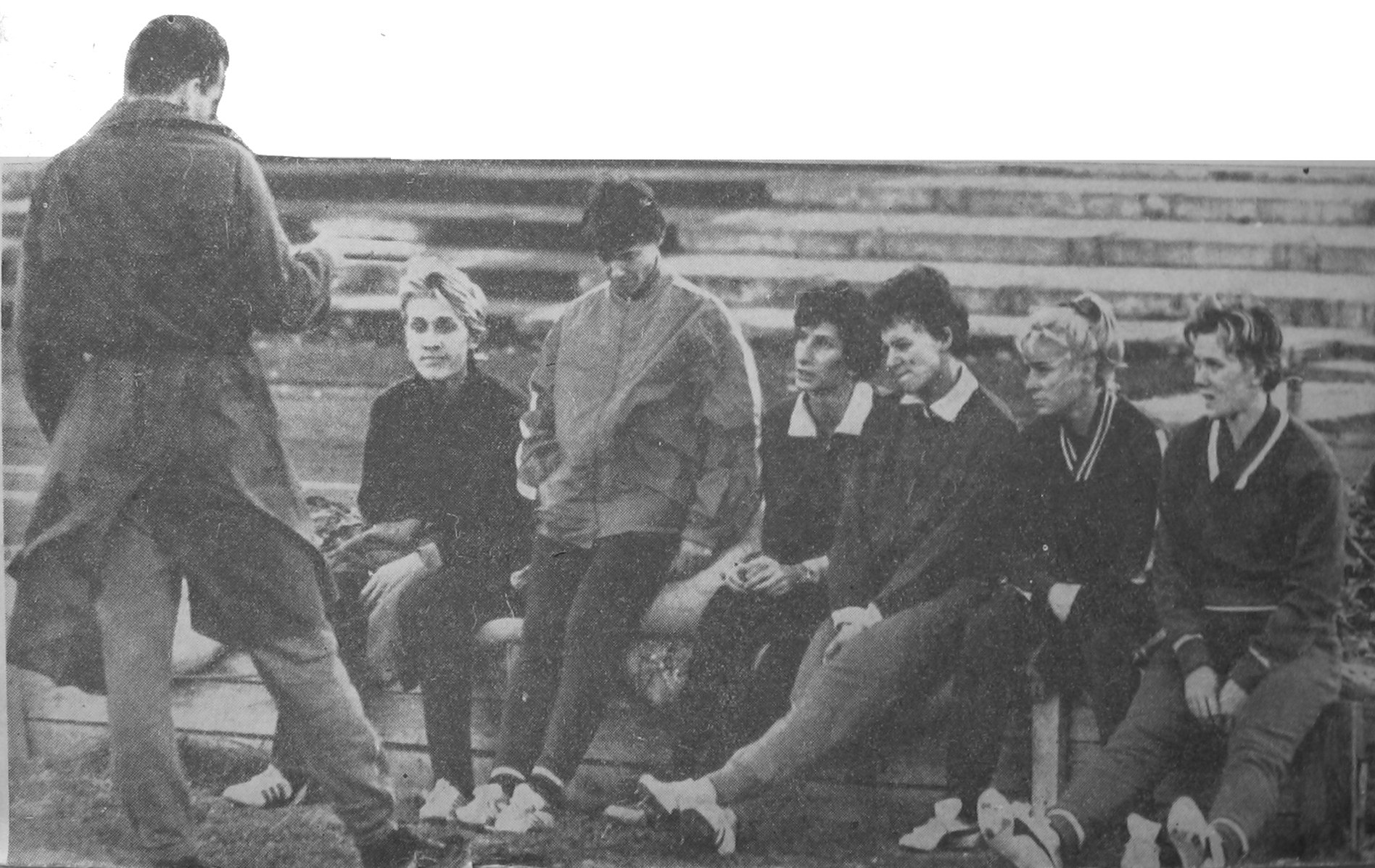

A 1964 image of Polish athletes (from left to right) Ewa Kłobukowska, Maria Piątkowska, Irena Kirszenstein, Halina Górecka, Barbara Sobotta and Teresa Ciepły (credit: J.Szewiński, H. Sourek/Lekka Atletyka, under public domain)

After the success of Poland’s female sprinters at the Tokyo Olympics, the head of the German Athletics Association, Max Danz, publicly questioned whether Kłobukowska and her relay teammate Irena Szewińska were really women.

At the event in Kyiv, Kłobukowska was refused permission to take part following a request from Soviet and East German officials, who said that her “gender status is undetermined”.

Redemption, reform and recognition – but no apology

In 1991, Malcolm A. Ferguson-Smith, a Cambridge University professor, and Elizabeth A. Ferris, the medical officer for the Modern Pentathlon Association of Great Britain, co-authored a paper for the British Journal of Sports Medicine in which they cited Kłobukowska’s case as an example of the need for change in gender verification in sport.

They argued that most athletes who had failed gender tests were “unjustly disqualified”. In Kłobukowska’s case, they said that she most likely had a rare condition called “XX/XXY mosaicism”.

The year after Ferguson-Smith and Ferris’s article, the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) ended compulsory sex screening for all athletes. That same year, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) stopped using the Barr body test and, following the Atlanta Olympics in 1996, ceased chromosome testing entirely.

Kłobukowska’s case also led to a change in the way that such incidents were dealt with by the athletic authorities. After she faced the humiliation of having her test results disclosed to the public, it was decided that from then on any findings would remain confidential.

In Sep '67 these Polish officials were on the right side of history. "You must allow for those persons who are complicated to be able to take part in sports" Ewa Kłobukowska, who has XX/XXY mosaicism, broke the 100m WR in 64. She failed an IAAF gender test and later bore a son. pic.twitter.com/mlxDQW3vzW

— patbirgan (@patbirgan) May 9, 2019

Kłobukowska, who is now aged 77, received redemption and recognition later in her life. In 1998, she was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta, Poland’s second-highest civilian award. In 2011, that was upgraded to the Officer’s Cross and in 2021 to the Commander’s Cross.

However, the Polish Olympic Committee notes that, despite the testing Kłobukowska faced having been shown to be unreliable, “no one [in the international athletic authorities] has so far apologised or rehabilitated this victim of a medical error”.

Even now, although Kłobukowska’s biography on the Olympic website notes that she failed a gender verification test, you must click an unlabelled button at the end of the page to reveal that “the test procedures were later found not to be accurate and her case led to a change in the gender verification policies by the IOC”.

Kłobukowska herself has largely avoided the public eye and has not spoken about her experiences to this day, refusing requests for interviews.

One of her coaches, Edward Bugała, told news website Onet in 2020 that “Ewa doesn’t want to go back to those days. She never came to terms with what happened, and that kind of trauma stays with her for life”.

A Polish athlete has criticised those who have been suggesting that the Mexican judoka who defeated her at the Olympics is male.

Among those to make such insinuations are a Polish constitutional court judge and a former government minister https://t.co/jMDMaVWBzu

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) August 1, 2024

Yet while Kłobukowska may have faded from public consciousness, the issues surrounding her case certainly have not.

This has been on clear display at this year’s Olympics, where debates over gender testing, concerns over fairness, claims of political interference and simplistic narratives about “men” competing with women closely echo the events of 1967 and their aftermath.

In a quirk of fate, when Lin Yu-ting, one of the boxers at the heart of the current controversy, won gold in Paris on Saturday, she did so by defeating a Polish opponent, Julia Szeremeta. That led many in Poland to declare the contest unfair, with some even labelling Lin a man.

Yet few have cared to recall the case of Kłobukowska, and the complexities and injustices it highlights.

Julia Szeremeta has won Poland's first ever Olympic medal in women's boxing.

She took silver after losing the featherweight final to Taiwan's Yu Ting Lin, one of the boxers who has been embroiled in a gender eligibility controversy during the Paris games https://t.co/3NyRzd8aPK

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) August 10, 2024

Main image credit: J.Szewiński, H. Sourek/Lekka Atletyka (under public domain)

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.