By Stuart Dowell

Poland was once home to more than a thousand shtetls – the name given to small towns with a majority Jewish population. As a result of the Holocaust, few traces remain of them today. But the folk paintings of Mayer Kirshenblatt – based on his childhood memories – give a unique insight into the life of Polish Jews before the Second World War.

When Mayer Kirshenblatt was a boy living in Opatów (known as Apt in Yiddish) in the 1920s, there was always a pot of soup on the kitchen stove. It would sit on one of the back rings and simmer on a low heat all day.

Every now and then, his mother would toss ingredients into the pot – a carrot, a potato, a handful of groats, pieces of chicken and even beef. By the end of the day, the soup was ready. This pot was never washed, to preserve the flavour that remained inside.

“My mother was an excellent cook. She was able to make a meal for the whole family from almost nothing,” Kirshenblatt recalled.

Years later, as a retiree living in Canada, Kirshenblatt painted the family kitchen with the soup pot on the stove. It was the first of around 300 paintings depicting Jewish life in Opatów and capturing in vivid detail the world of the shtetl lost to the Holocaust.

Mayer Kirshenblatt, Portrait of klezmer musicians in photographic studio, 1996, acrylic on canvas. Photo credit: POLIN Museum Collection

Seventy of these acrylic paintings are the subject of a new exhibition titled “(post)JEWISH… Shtetl Opatów Through the Eyes of Mayer Kirshenblatt” at Warsaw’s POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews.

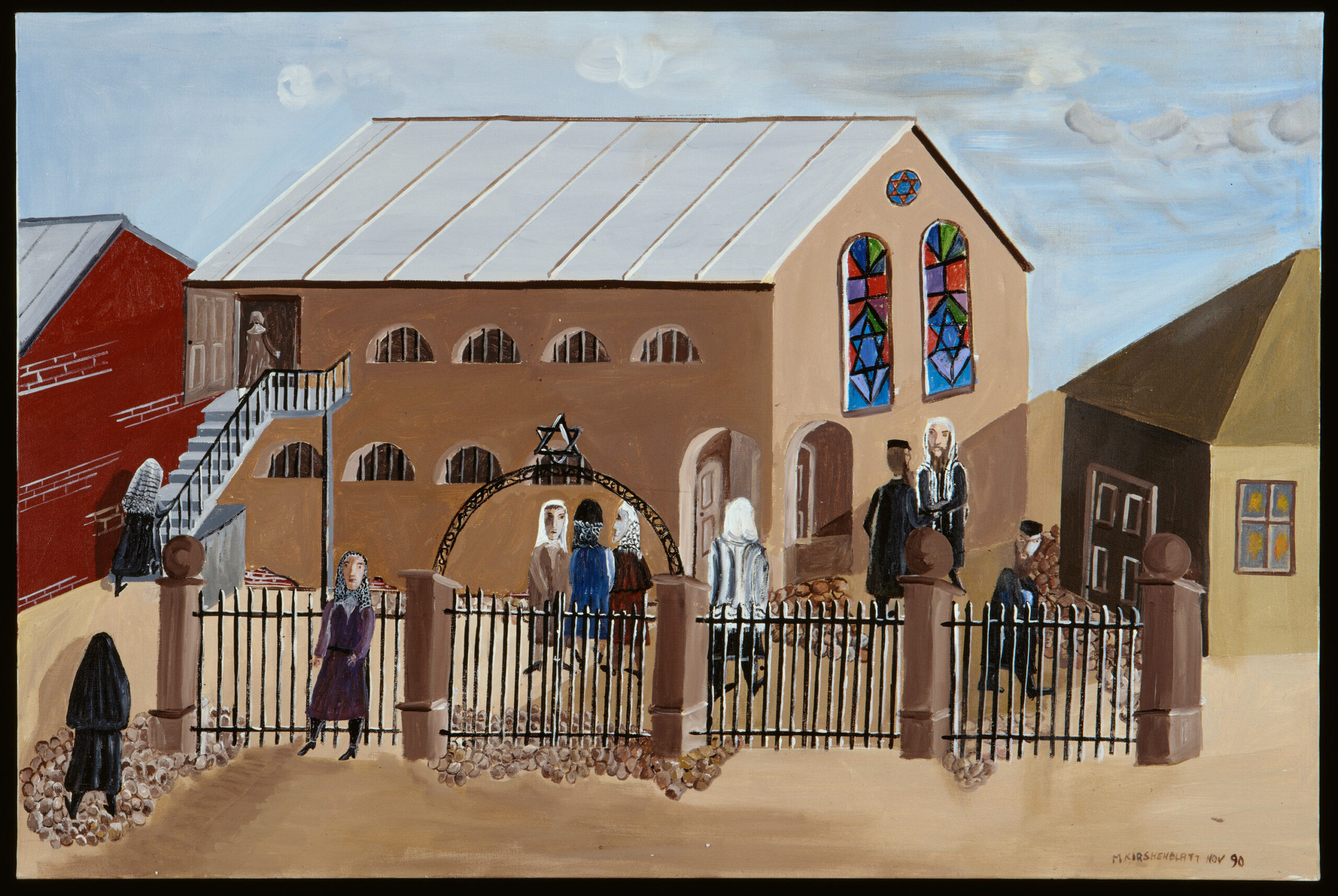

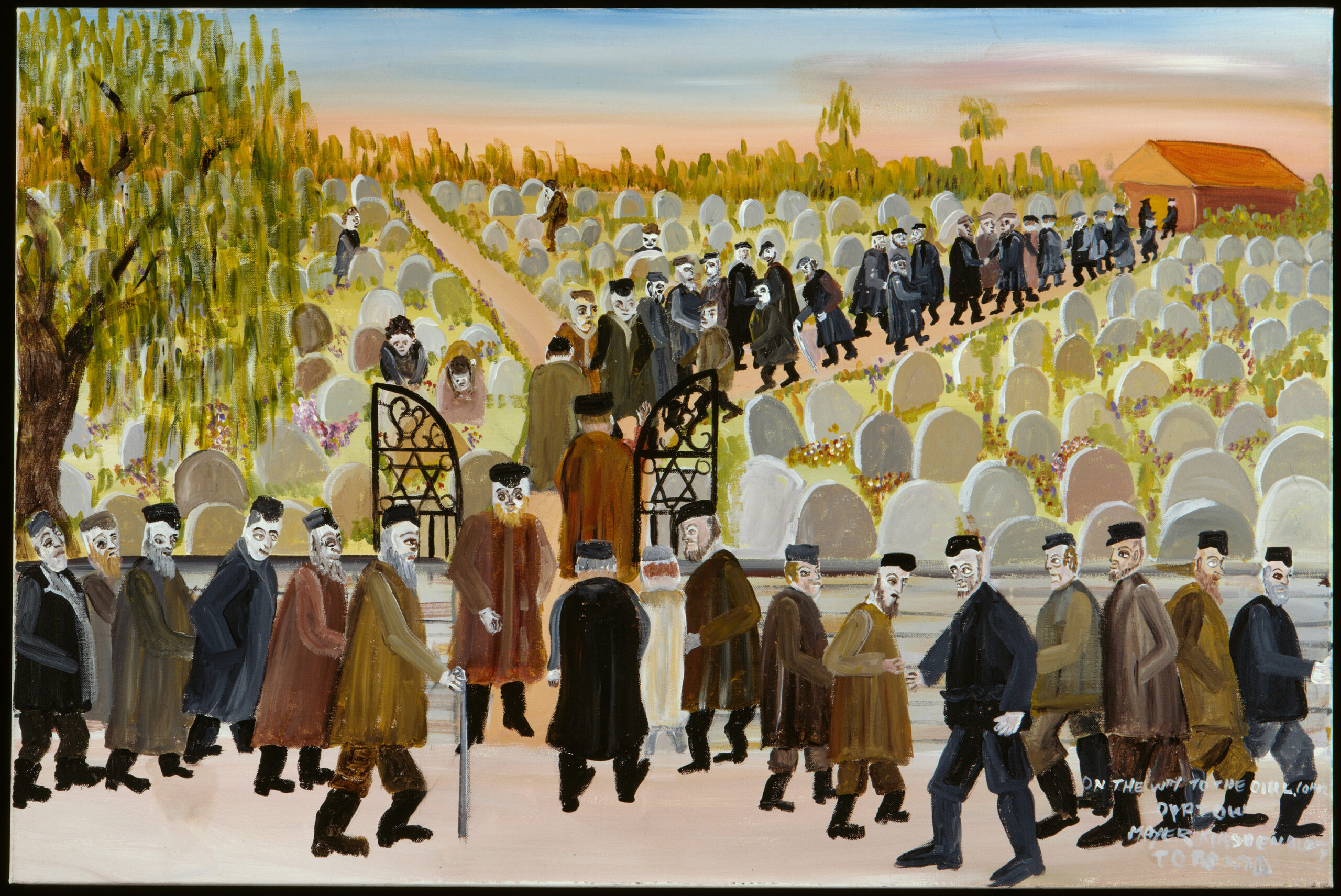

Kirshenblatt painted from memory: the synagogue, men washing in the mikvah ritual bathhouse, the cemetery, townspeople, school scenes including a pupil being flogged by a teacher, an illicit cigarette factory, the illegal slaughter of a cow, bagel sellers, a water-carrier, circus performers.

There were no forbidden subjects. One painting depicts a visibly pregnant bride at her wedding, and another features the town’s two prostitutes, Jaźdka and Świderka.

Opatów is now located in southeastern Poland. Before the Second World War, it was one of over a thousand shtetls – small towns in which the majority of residents were Jewish – in what are now Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania and Belarus.

In Poland, shtetls emerged in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, on the eastern fringes of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Magnate families established private towns and invited Jews to boost trade and crafts, which they could tax.

Jews were given land for a cemetery, as well as permission to build a synagogue and open a mikvah, crucial for a functioning Jewish community.

Mayer Kirshenblatt, The synagogue from the outside, 1990. Photo credit: POLIN Museum Collection

In the 14th century, there were no more than a thousand Jews living in Poland. By the middle of the 18th century, the number was already 750,000.

Jews in the shtetls made their living from trade and crafts: shoemaking, tailoring, carpentry and sometimes small-scale manufacturing.

They ran mills and tanneries. In Opatów they produced brushes, clothing and headwear.

The heart of the shtetl was the market, where a mix of cultures – Yiddish, Polish, Ukrainian, Russian – could be seen and heard.

The life of a shtetl’s Jewish community was run by the kahal, which organised religious life and charity, supplied kosher meat and distributed tax money. It maintained the cemetery, the mikvahs and the schools for poor Jewish children.

Mayer Kirshenblatt, At the cemetery, on the way to ojel, 1996, acrylic on canvas. Photo credit: POLIN Museum Collection

Donations for the needy were collected from everyone to help the beggars and the sick. Births, weddings and funerals were experienced by the whole community. Privacy was a foreign concept. Newcomers had to obtain permission from the kahal to settle, set up a new workshop or marry a local.

Failure to follow the rules resulted in being banned from the synagogue, flogging or even expulsion from the community.

Opatów differed little from other shtetls. Before the war, its population of about 9,600 included more than 5,200 Jews.

A trove of valuables believed to have been buried during WWII, most likely by Jews, has been discovered during construction work in the city of Łódź https://t.co/n9eoAlcPgZ

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) June 6, 2023

Andrzej Żychowski, a local historian and the author of a book about the history of Jews in Opatów, emphasises the town’s multiculturalism. “Despite their differences, a spirit of cooperation thrived in Opatów. The central market square was a melting pot where Jewish merchants, Christian farmers and local Poles mingled.”

He adds that the Jewish community was economically diverse. Its small but influential class of wealthy residents included the Mandelbaum family, whose soap factory and oil mill were cornerstones of the local economy.

“Most lived more modest lives,” continues Żychowski. “Living conditions were undoubtedly cramped, with as many as three or four people sharing a single room.”

Jewish Street in Opatów, 1930s. Photo credit: the collection of J. Brudkowski

What sets Opatów apart today is its visual chronicler, Mayer Kirshenblatt, who was born in the shtetl in 1916.

His father owned a leather business and was also a shoemaker. In the 1920s, the theft of a shipment of hides plunged the family into poverty, leading to their emigration in 1934 to Canada, where they settled in Toronto.

In Opatów, Kirshenblatt attended the Jewish cheder and later a Polish school, though he often skipped classes and had to repeat a year. His true passion was observing town life, earning him the nickname Crazy Mayer from the townsfolk.

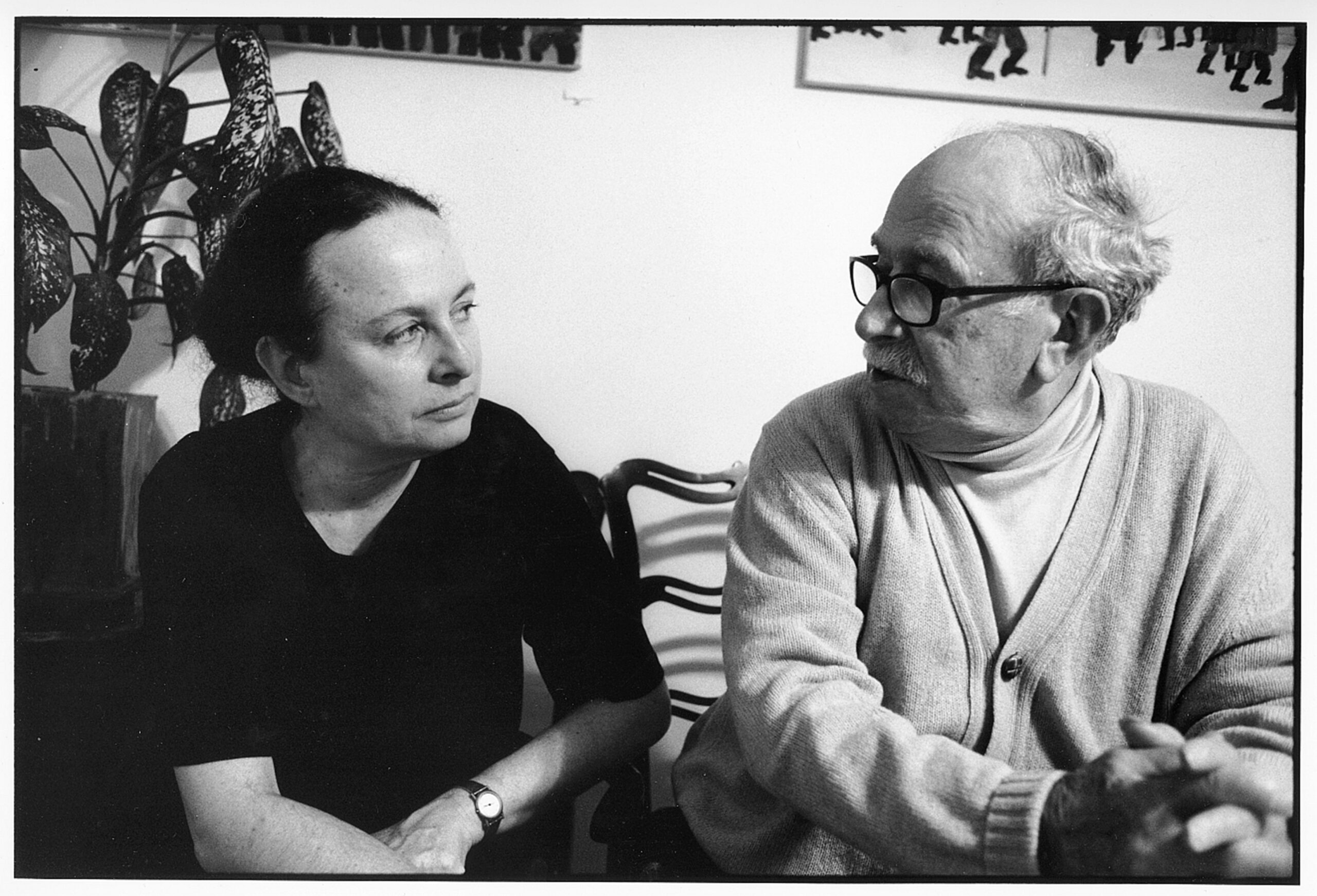

Yet Kirshenblatt ’s memories of Opatów might have remained locked in his mind if not for his daughter Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, a historian, folklorist and professor emeritus at New York University, who is also the chief curator of the permanent exhibition at POLIN.

“It all started in 1967, when I began interviewing him. I recorded these conversations for almost 40 years,” she recounts. The interviews continued almost until his death in 2009.

Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett with her father, Mayer Kirshenblatt, ca. 1990. Photo credit: by Frédéric Brenner

After much persuasion, she convinced him to paint his recollections when he retired from running his own paint and wallpaper store. At the age of 73, he began to pour his memories onto canvas, continuing for the next 20 years.

One painting is a self-portrait showing him returning home holding a single herring his mother had sent him to buy for the family dinner.

The fishmonger wrapped it in a narrow strip of newspaper, as a full sheet was too precious. On the way home, Kirshenblatt would lick the salty brine, savouring every drop.

A male herring was preferred because his mother would remove the semen sac and mix it with chopped onions, vinegar and sugar, creating a tangy dipping sauce for bread.

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett emphasises that her father’s paintings are unique for one fundamental reason.

“He left in 1934, meaning he was not directly affected by the trauma of the Holocaust,” she explains. “His memories of Poland were not filtered through the experience of that trauma. This is an extraordinary gift.”

Ryszard Ores was the only one in his family to survive the Holocaust. Yet despite his experiences in the ghettos and camps of German-occupied Poland, he regularly returned after the war, always regarding himself as a Pole

A new exhibition tells his story: https://t.co/eWnCBLnm5S pic.twitter.com/CyFij8dkiB

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) September 13, 2021

One of his paintings features the mikvah. Kirshenblatt recalled that men used it on Fridays and women on Thursdays, or after menstruation, as only the ritual cleansing allowed them to resume sexual relations.

Although the mikvah no longer exists, the building survived the war and now houses the Opatówek fudge factory.

To understand how the building had changed inside, the exhibition curators scanned the interior with a laser.

“By doing so, we discovered where exactly the pool was located,” says Dr. Natalia Romik, one of the exhibition’s curators. “It turned out that today this is where the ladies wrap fudge by hand.”

A new album of Polish-Jewish 1930s tango celebrates the rich and diverse interwar music scene in Poland and can act "as a bridge for Israelis and Poles to share our common heritage and history" https://t.co/zeguaLx55c

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 10, 2020

When Kirshenblatt lived in Opatów, Jews made up about 60% of the population. The town was an important centre of Polish Hasidism – a prominent figure in the movement, Avraham Yehoshua Heshel, served as its rabbi for eight years.

In 1940, the German occupiers established a ghetto in Opatów, and from 20-22 October 1942 approximately 6,500 Jews were deported from the town to Treblinka death camp, where they were murdered.

Around 300 Jews from Opatów survived the Holocaust; however, none of them chose to remain in the town.

In today’s Opatów, there are almost no remaining physical traces of the shtetl. Only the buildings of the former cheder and mikvah have survived.

Wooden hanukkah menorahs from Opatów. Photo credit: Iwo Ksiazek (collection of J. Brudkowski)

The 17th-century synagogue is now a pile of rubble, though it survived the war. The Jewish cemetery was turned into a park after the war.

Recently, a small lapidarium with matzevot tombstones found nearby has been created in the park.

“On the building that once housed the Jewish school is a Jewish star etched into its façade. It is a rare sight in Poland today,” notes Żychowski. Another building has an indentation that once held a mezuzah parchment inscribed with Hebrew verses from the Torah.

In a blend of preservation and art installation, the exhibition curators purchased timber beams from a half-destroyed former Polish-Jewish school in the town. Back in Warsaw, these beams were used to create the exhibition’s scenography.

A new collection of photographs captures the changing face of Kazimierz, Kraków's former Jewish quarter, over the decades, from its postwar decline to a recent revival https://t.co/jvvbHaWawp

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 15, 2022

The display cases made from this wood contain artifacts once owned by Opatów residents, including unique wooden menorahs from the war (likely made after silverware was looted), a Seder plate, a fragment of a destroyed Torah scroll, a synagogue key, and fragments of candelabras from the synagogue, which feature in one of Kirshenblatt’s paintings.

The exhibition also includes pre-war photos of the Jewish Street (ulica Żydowska) and pictures of local people, such as a woman carrying water.

Kirshenblatt’s collection is now permanently held by POLIN, which plans to display it in a mobile exhibition touring some of today’s former shtetls.

“(post)JEWISH… Shtetl Opatów Through the Eyes of Mayer Kirshenblatt” is open at the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews until 16 December 2024.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: POLIN Museum Collection