On 1 March, less than a week after Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, I arrived at the Polish-Ukrainian border to talk to the refugees that had started pouring into Poland.

By that morning, 410,000 people had already crossed the border, often with no more than one suitcase of possessions, gathered hastily before departure. Millions followed in the months to come, and around a million still remain.

As I approached a group of refugees sitting around a bonfire in the small village of Medyka, Poland’s busiest border crossing with Ukraine, a young man looked at me, smiled, and started talking. And I understood absolutely nothing.

“English?” I responded hesitantly, pointing to the press ID dangling off my neck. “French? Français? No?” He shook his head and looked down. I tried several more times, with different groups, getting almost the same answer every time.

Refugees in Medyka. A still from a video taken on 1 March 2022.

Intuitively, I could see potentially fascinating stories around me: a little girl with a cat, people gathered around power generators, scrolling frantically through their phones, a mother of three looking for a safe place to stay. And all I had was Google Translate.

I felt powerless as a journalist and as a human being. It was there and then that I decided I need to learn Ukrainian – and I am far from the only one.

In mid-March, Duolingo, a leading language learning app, reported that since the start of the war in late February, the number of people studying Ukrainian had increased by 577% globally and by 2,677% in Poland.

Anna

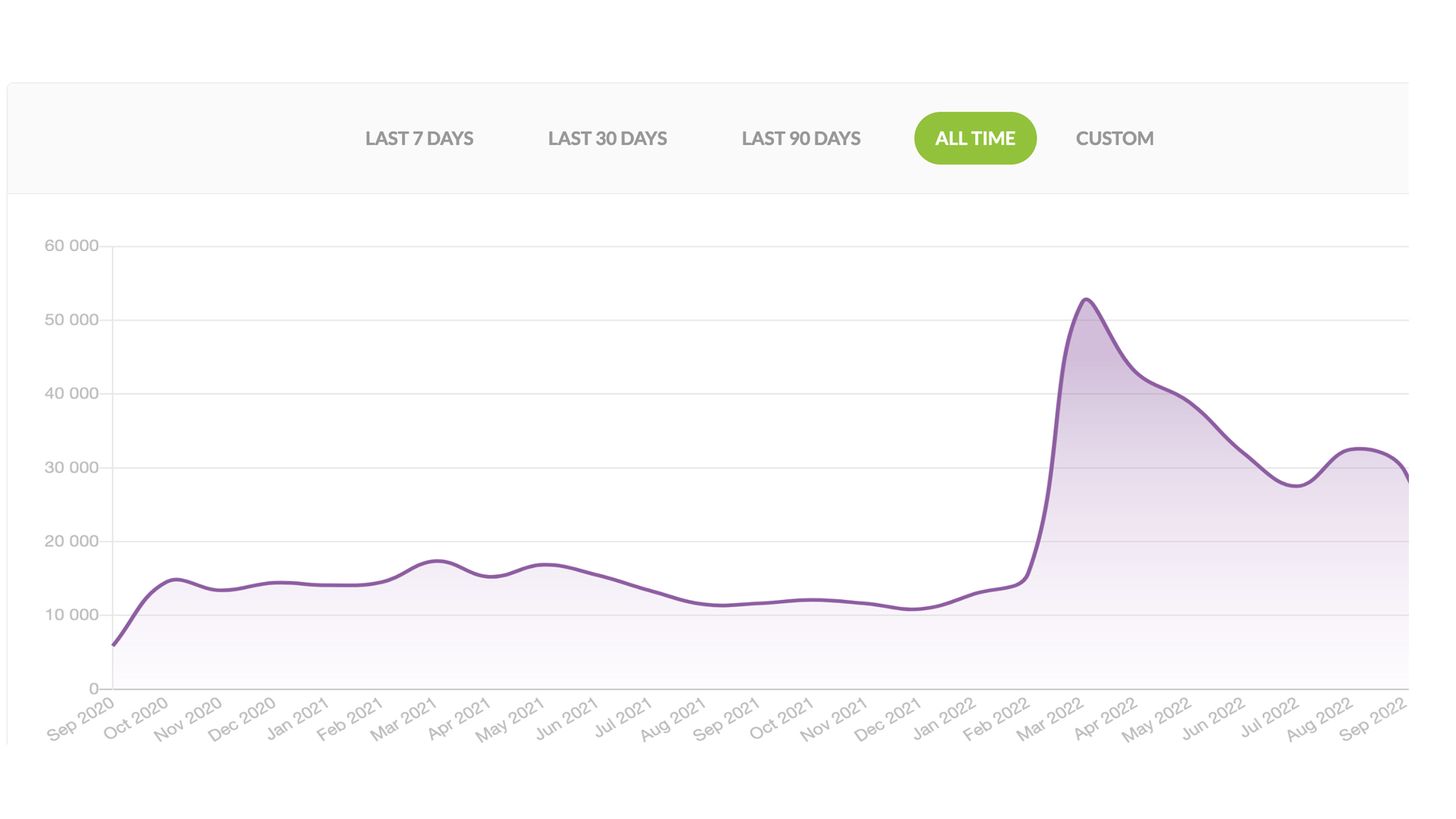

Those figures are corroborated by Anna Ohoiko, the founder of the Ukrainian Lessons Podcast, an audio course in learning the language, which saw a five-fold spike in the number of listeners in the days after the war began. Even though this number has gradually declined since, it remains around three times higher than before the war.

Number of listeners to Ukrainian Lessons Podcasts. Source: Anna Ohoiko

“Before the war, there were mostly practical reasons to learn Ukrainian. The most popular reason, I would say… was a family reason because someone married someone in Ukraine and they had to communicate with the family of their husband or wife,” Anna tells us.

“But now people without any connection to Ukraine learn the language for many other reasons, for example, to support Ukraine’s fight, to support refugees, to talk to Ukrainians who had to flee.”

Ohoiko’s learners come from all around the world, but Poland is among the leading countries in terms of the numbers. In fact, Warsaw is the city with her third largest number of listeners, after Kyiv and London, Canada.

Mateusz

A day after the war broke out, Mateusz Górny, a 38-year-old camera operator for Polsat, one of Poland’s three main TV stations, wrote to his acquaintance in Ukraine. With the help of Google Translate he wrote “Yakov… we offer you help and support if you want to come to Poland with your family.”

The reply came back after roughly 15 minutes.

“I need help,” it read. “My wife is in Germany right now. She cannot come back. And I am in Kyiv with my kids in the basement. So if it is possible, can you help my wife, take care of her in Poland?”

Mateusz Mezler Górny at his home in Warsaw.

By the time I arrived in Medyka, Yakov’s wife Olga – who spoke only a few words of English – and his aunt Natalia were in Warsaw with Mateusz.

“I had to rely on Google Translate for communication,” says Mateusz. “Those days my head was close to exploding from thinking in different languages.”

Soon he had to leave Warsaw to cover the conflict himself.

“I was so pissed off that I didn’t know how to express myself in Ukrainian,” he said. “But I had this thought – still being in contact with Olga via messenger, using Google Translate – that the next time I see her, her kids and her husband, probably in the better times, I would really like to have coffee with them and talk to them in Ukrainian.”

Mateusz, who already speaks English and German, added that he had always wanted to learn a non-Western language.

“So I thought that it was perfect timing for nations like Poland and Ukraine to learn from each other,” he said. In Lviv, he found Dmytro.

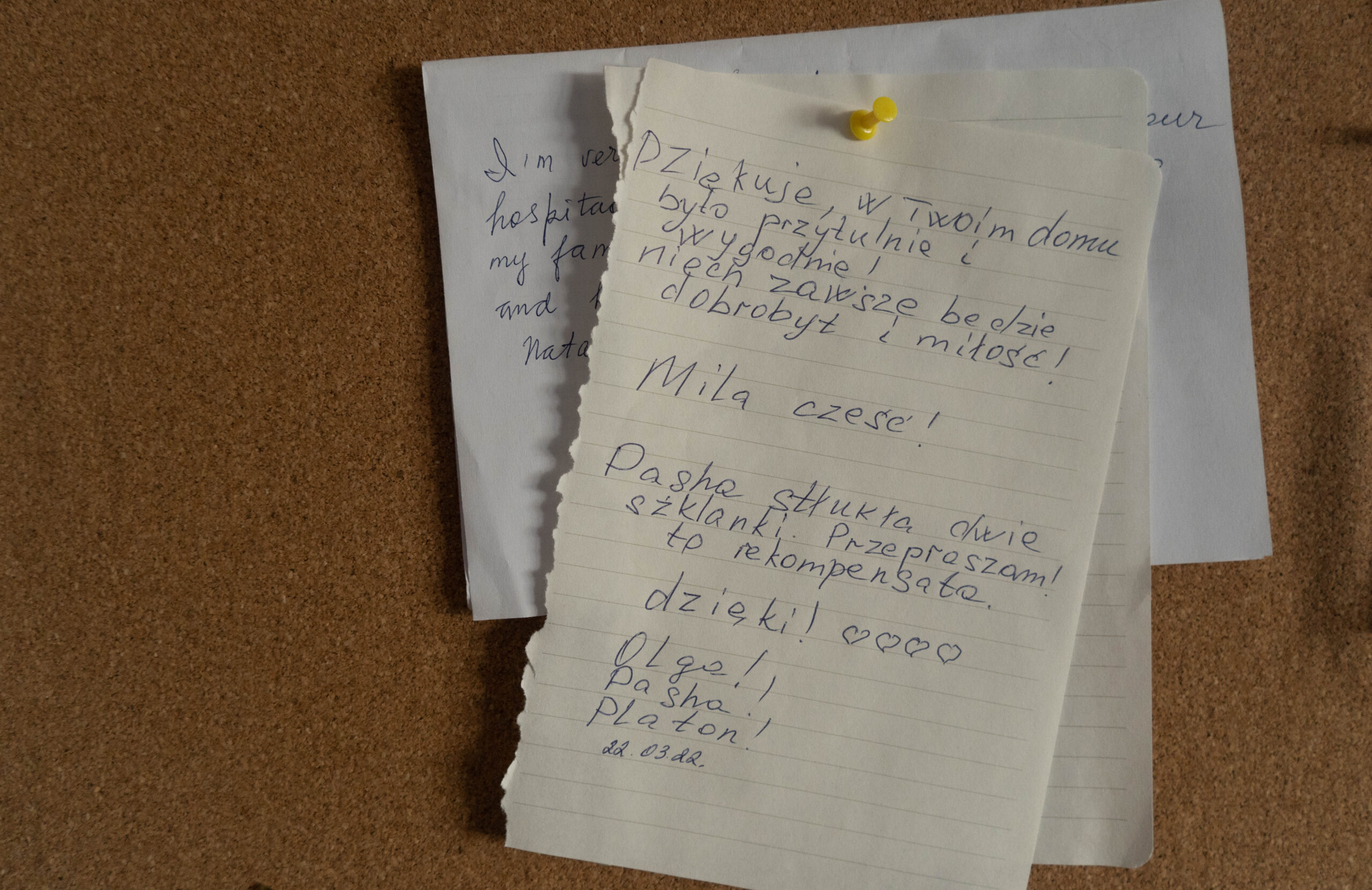

A letter left for Mateusz by Olga, a Ukrainian woman whom he received in his home shortly after the war broke out. Using Google Translate, Olga wrote in Polish: “Thank you, your house was cosy and comfortable! May there always be prosperity and love! Kind regards.”

Dmytro

Dmytro Dymydyuk, a 28-year-old PhD candidate at Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, who had been making ends meet by tutoring high school seniors, lost almost all of his students – and thus his income – when the war broke out.

“I was shocked,” he says. “I even cried a little bit. And in my head, all my world collapsed.”

He convinced his wife, Julia, 25, also a tutor, to start marketing their services to Poles wishing to learn Ukrainian, as both of them speak Polish. Quickly they gathered over a dozen students.

Dmytro Dymydyuk and his wife Julia Hryshko, 25.

“[These were] elderly people, young people, different people who wanted to learn Ukrainian for different reasons,” he says, though adding that around half of them were journalists.

He met Mateusz after being asked to give an interview to Polsat about the war. Afterwards, Mateusz told Dmytro that he would like to start learning Ukrainian.

“And then we agreed to hold his first lesson after his return to Warsaw,” says Dmytro.

Łukasz

Another of Dmytro’s students, Łukasz Radtke, a 39-year-old engineer, has been passionate about learning languages his whole life. A week into the war, he started to look for a Ukrainian teacher for himself and his wife. But unlike me or Mateusz, he did not need to learn the language for his job.

He saw it, however, as a way to support Ukrainians. He thinks that the two nations can become closer by learning each other’s languages, helping create a stronger eastern European voice on the continent.

“We should support Ukraine militarily, we should support Ukraine financially, and for sure we should build long-term relations,” he says, adding that a big part of learning the language is learning about Ukrainian culture.

Billboard in central Warsaw. It reads “Find a job in Poland”, written in Ukrainian.

Liudmyla

One day upon arriving at his office, Łukasz found out that his company had hired a new coordinator for foreign employees. It was an energetic 35-year-old woman from Ukraine, Liudmyla Kiriachok, who had come to Poland in March.

Łukasz saw it as the perfect opportunity to try out his Ukrainian.

“At the beginning, she thought that I am Ukrainian,” Łukasz recalls with a smile.

Liudmyla tells me that she was pleasantly surprised to learn that Poles were learning her language. It made her feel at home “but in a slightly different city”, she says.

Stand with Polish and Ukrainian flags, central Warsaw.

She spoke with particular excitement about how her children’s schoolmates were also trying to learn a few words in Ukrainian.

“Alicja, do you understand?! Kids!” she repeated a few times. “It was so unusual, because we came to visit… We are forcibly displaced. And no one should adjust to us, we should be the ones adjusting.”

Liudmyla has herself been learning Polish, like many other Ukrainian refugees.

A study published by Poland’s central bank showed that, while around half of the refugees that crossed the Polish border in the first two months of the war understood some Polish, only 5% declared knowing the language.

However, another language learning app, Babbel, reported later that 40,000 Ukrainians had signed up for its free Polish course, created specifically for refugees.

Why learn?

The title of the first ever book on Ukrainian grammar – Alexei Pavlovsky’s The Grammar of the Little Russian dialect, published in 1818 – is revealing.

At the time, the name “Ukraine” and the “Ukrainian language” were forbidden, and the language itself was considered a dialect of Russian.

In a foreword to the centenary edition of The Grammar, Ukrainian linguist and historian Ivan Ohienko wrote that it was published at a time “when in Russia they knew nothing more about the Ukrainian language, except for a common rumour that it was like ‘Russian spoiled by Polonisms’.”

These similarities can be seen from the very first lesson. Poles and Ukrainians both say “tak” for “yes”, while Russians say “da”.

Each day for at least the last eight years, Russian TV has been publicly mocking the Ukrainian language. Today I will try to explain the subtle meaning of this mockery, which could be challenging to understand without knowing Ukrainian and Russian languages.

— Mariam Naiem (@mariamposts) November 9, 2022

There are, of course, “false friends” – words that sound the same but mean different things – yet the languages are similar enough that learning vocabulary is not a major problem. Beginners can get by with some creativity – by adding Ukrainian endings to Polish words, for example, or pronouncing them with an ever so slightly different accent.

Using these tricks, I can confidently say that four months was enough for me to understand 80-90% of speech, to watch films without subtitles, and to generally be understood. The people I spoke to seemed to share my experience.

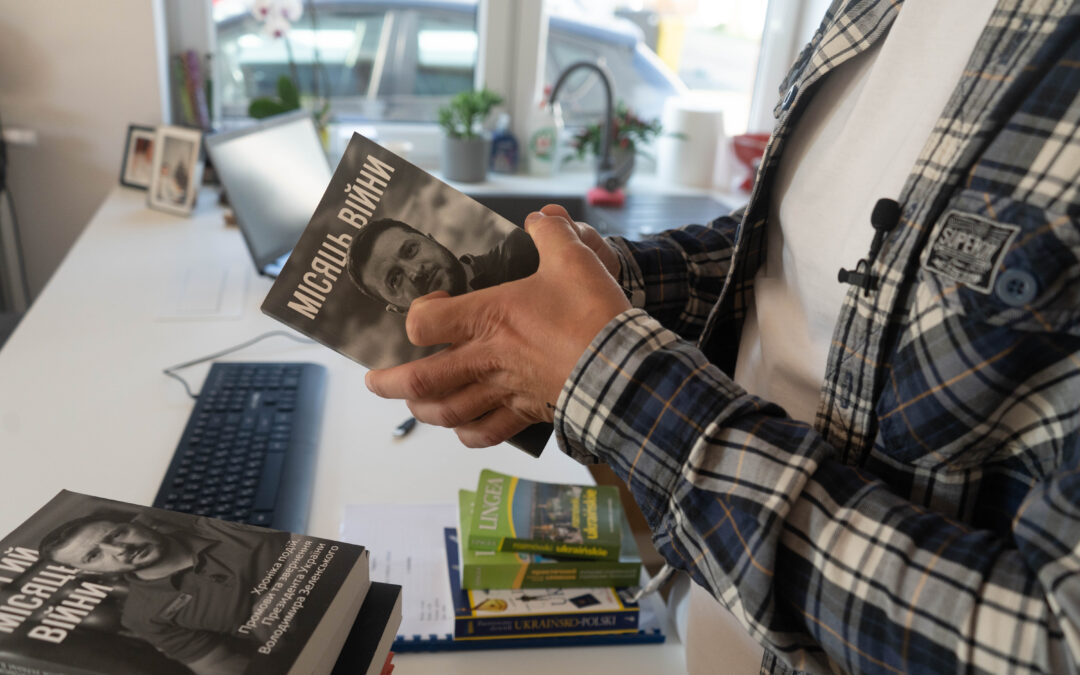

Łukasz listens to Ukrainian podcasts on his way to work, Mateusz brought a stash of books from his travels to Ukraine, and Liudmyla dances with her children to Polish songs.

Books in Ukrainian Mateusz brought from Ukraine.

Everyone I’ve talked to said, in one way or another, that learning the language – be that Polish or Ukrainian – helps them first and foremost to understand the culture of their neighbour.

“By learning a foreign language we can expand the world for ourselves,” says Dmytro’s wife Julia.

While the true scope of this bridging of the linguistic language gap between the two Slavic nations is impossible to assess, we can already see how the languages influence each other. The war, for example, revived a linguistic debate over how to say “in Ukraine” in Polish.

The war in Ukraine has led Poles to reconsider how they say "in Ukraine"

There has been a shift away from the traditional "na Ukrainie" (which some think makes a country seem more provincial) and towards "w Ukrainie" (which better emphasises independence) https://t.co/rZjgCDGFFB

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 4, 2022

On a personal level, were the dozens of hours spent learning it worth it?

Yes. A week before writing this article, I met an elderly couple at Warsaw airport. They struggled to communicate with an airport employee.

“Excuse me. Are you from Ukraine? Maybe I can help, I speak a little Ukrainian,” I said.

The lady grabbed my arm and explained that she was travelling to the US with her husband. They decided to join their son living in New York after bombs fell on their hometown, Lviv, just a few days earlier – in what the media speculated, was Putin’s retaliation for the destruction of the Crimean bridge.

“I will never forget you,” she said, even though I did not really help them much beyond pointing to the right gate and saying, in their own language, that everything will be alright… все буде добре.

All photos taken by the author

Alicja Ptak is deputy editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland and a multimedia journalist. She has written for Clean Energy Wire and The Times, and she hosts her own podcast, The Warsaw Wire, on Poland’s economy and energy sector. She previously worked for Reuters.