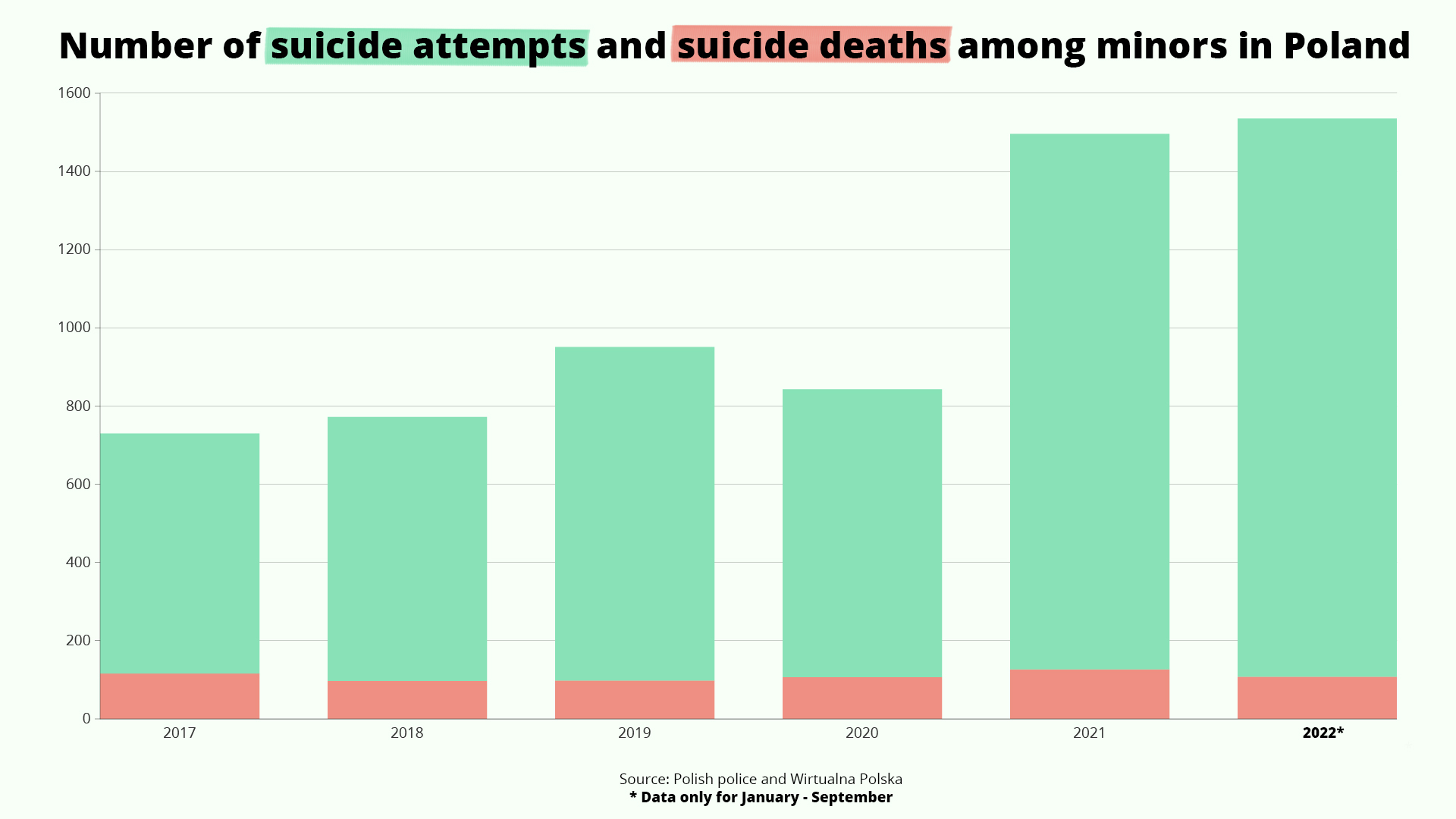

A record number of suicide attempts by children and adolescents have been noted in Poland this year. Police data show over 1,500 by the end of September, already more than in the whole of last year, which previously had the highest ever figure.

In the last five years, the number of suicide attempts among minors has more than doubled. Experts point to the underfunded, overstretched and outdated mental health support system and the lack of psychiatric support during the pandemic as culprits.

In the first nine months of this year, 1,535 suicide attempts among children and adolescents were recorded in Poland, with 108 resulting in death, according to police data obtained by news website Wirtualna Polska. That was more than the 1,496 attempts in the whole of 2021.

Source: Polish police and Wirtualna Polska

In total – across all age groups – 11,032 Poles attempted suicide in the first nine months of 2022 and 3,849 of these attempts ended in death.

Suicide attempts were most common among girls between the ages of 13 and 18. In this age bracket, in the first nine months of 2022, as many as 1,137 girls tried to end their lives. Among children aged between seven and 12, there were 54 suicide attempts but none resulted in death.

This year’s figures follow a previous sharp rise in suicide attempts by minors in 2021.

“Psychiatric wards for children and adolescents are overcrowded,” psychologist Michalina Kulczykowska of the Dajemy Dziecom Siłę (We Give Children Strength) foundation told Wirtualna Polska.

She also pointed to a Supreme Audit Office (NIK) report from 2020 showing that not all of Poland’s 16 provinces even had psychiatric hospitals for children.

“The situation is also difficult in schools. Not every institution has a psychologist at all, because there is no such obligation. And even if there is, the number of their working hours, for example, is very small,” she added.

“I often hear on the phone that children are trying to get to a school psychologist. Parents do not always have the money to provide their children with specialist help. It then turns out that there is a psychologist on duty at school, but the children see them once a month when they are running somewhere in the corridor,” said Kulczykowska.

A separate audit published by NIK this year found that remote learning during the pandemic worsened children’s mental and physical health. NIK criticised the education ministry for not introducing a support programme for children quickly enough.

Earlier this year, Poland’s health minister noted that the state of young people’s mental health reveals the continuing trauma caused by the pandemic, adding that last year the number of psychological counselling sessions for children and teenagers was twice as high as in 2020 and two-and-a-half times the figure for 2019.

“We can see a huge increase in the interest or need for treatment [which is] exceeding all our expectations,” Adam Niedzielski said in April.

In 2021 Polish government announced a new package amounting to 220 million zloty of support for children’s mental health care.

The plan included the improvement of hospital infrastructure, the launch of a round-the-clock helpline, online support and prevention programmes, as well as easier access to specialists.

This year, however, state funding was withdrawn from a helpline for children and young people, founded in 2008 and run by the Dajemy Dzieciom Siłę foundation, which has managed to continue operating thanks to a crowdfunding campaign.

Main photo credit: Rod Long/Unsplash

Alicja Ptak is deputy editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland and a multimedia journalist. She has written for Clean Energy Wire and The Times, and she hosts her own podcast, The Warsaw Wire, on Poland’s economy and energy sector. She previously worked for Reuters.