Poland’s state historical body, the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN), which has prosecutorial powers, is reopening an enquiry into the so-called Lubin events of 1982, when three people died after riot police opened fire on a peaceful demonstration against the communist authorities.

Announcing the decision at a press conference marking the 40th anniversary of the events, IPN president Karol Nawrocki noted that the officers who fired the fatal shots have never been identified.

The reopened investigation, approved by Andrzej Pozorski, director of the Chief Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation and deputy prosecutor general, is part of a wider project taking a fresh look at crimes by the communist authorities in the 1980s.

For the IPN, “every life has value” and “the people murdered by the communist system” will all be remembered, Nawrocki said. “We will not forget a single victim from the 1980s, 1970s and other decades of colonial, communist Poland.”

Street protests took place in 66 towns and cities around Poland on 31 August 1982, which was the second anniversary of the Gdańsk Agreement, an accord reached between striking workers and the government that led to the formation of the Solidarity trade union.

However, the following year, the government had moved to clamp down on growing opposition by interning key members of Solidarity and imposing martial law in December 1981.

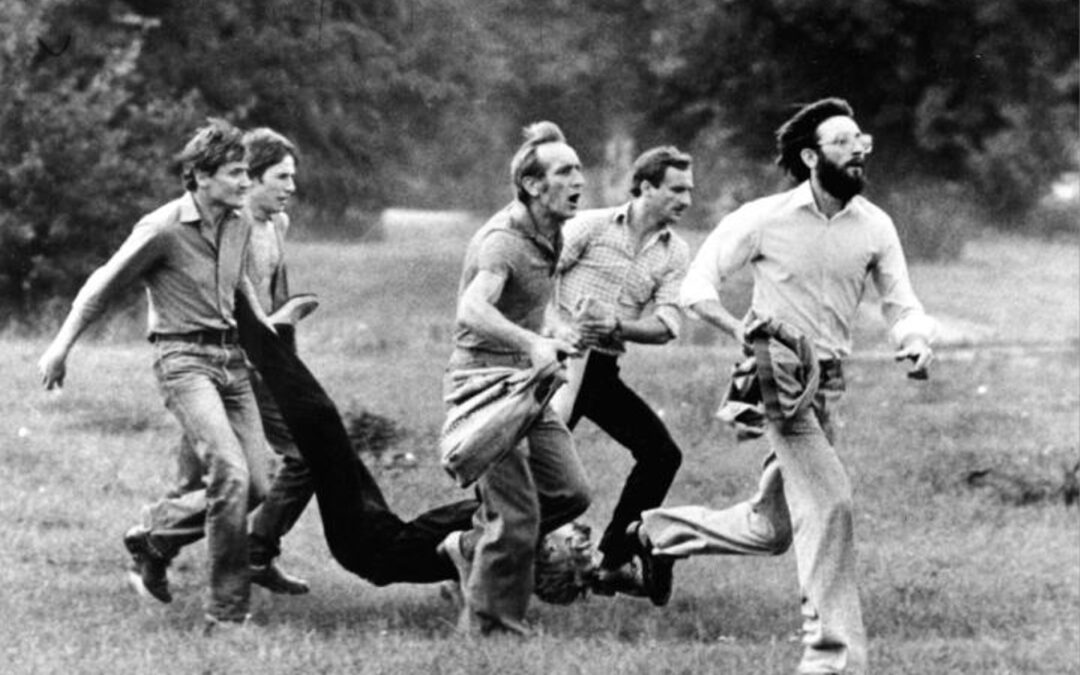

In August 1982, Lubin, a copper-mining town, was the site of one a number of protests to take place among industrial workers in the Lower Silesia province in southern Poland. While there were also deaths in other cities, the crackdown in Lubin was the bloodiest.

Three men – 28-year-old Michał Adamowicz, 25-year-old Mieczysław Poźniak and 32-year-old Andrzej Trajkowski – died after being shot by ZOMO, paramilitary police formations drafted in to deal with the demonstrations, and an unknown number of people were injured.

#TegoDnia w 1982 w Lubinie, w 2. rocznicę podpisania porozumienia gdańskiego, odbyła się demonstracja przeciwko stanowi wojennemu ”. Do historii przeszła jako Zbrodnia Lubińska, ponieważ milicja otworzyła ogień do pokojowej manifestacji, 3 osoby zginęły, wiele zostało rannych. pic.twitter.com/ayIzTexcx3

— Instytut Pamięci Narodowej (@ipngovpl) August 31, 2022

They had been part of a crowd of around 2,000 people who had congregated after the end of the first shift of miners. The protest featured slogans including “Lift martial law”, “Free Lech [Wałęsa]” and “Freedom for the imprisoned” as well as patriotic songs.

The police intervened after the organisers had requested demonstrators to go home, surrounding the crowd and then using tear gas and live ammunition on them.

Over the following days, the authorities began a cover-up operation. They removed evidence of the shootings – bulletholes were filled in, windows replaced, and all the rifles used were later sold to Algeria – and ordered officers to deny that weapons were used.

Speaking last week in Lubin at the monument to the victims, President Andrzej Duda said that the events in the town were one of the two great crimes of martial law, alongside the pacification of the Wujek coal mine, in which nine protesting miners were killed.

“Many witnesses of the events [in Lubin] said that it was a kind of hunt,” said Duda. “Here for an hour and a half in the town centre people were shot at, often in the back. People who were standing were shot at. They simply wanted to kill and did kill.”

In the 1990s, after the fall of communism, the crime was investigated, and eventually three police officers who commanded the units sent in to break up the demonstration were convicted. But the people who fired the shots have never been identified.

Earlier this year, the IPN also announced that it was resuming investigations into the deaths of opposition-linked priests who died in suspicious circumstances in the communist era.

Main image credit: Krzysztof Raczkowiak/Rzeczpospolita (public domain)

Ben Koschalka is a translator, lecturer, and senior editor at Notes from Poland. Originally from Britain, he has lived in Kraków since 2005.