With tens of thousands of new children from Ukraine already attending schools throughout Poland and many more – possibly hundreds of thousands – expected, schools are looking for additional staff to work with them.

The education ministry hopes retired teachers will return to work in newly formed preparatory classes, while local authorities are recruiting teachers from among the refugees who have arrived from Ukraine.

As of yesterday, 42,500 Ukrainian pupils had been registered in Polish schools since the Russian invasion forced them to leave their homes, education minister Przemysław Czarnek has revealed.

But these numbers remain small in comparison to the estimated 600-650,000 children to have arrived in Poland from Ukraine since 24 February.

The education ministry estimates that if 500,000 children started attending schools, their education would cost 10 billion zloty annually, notes financial news website Money.pl.

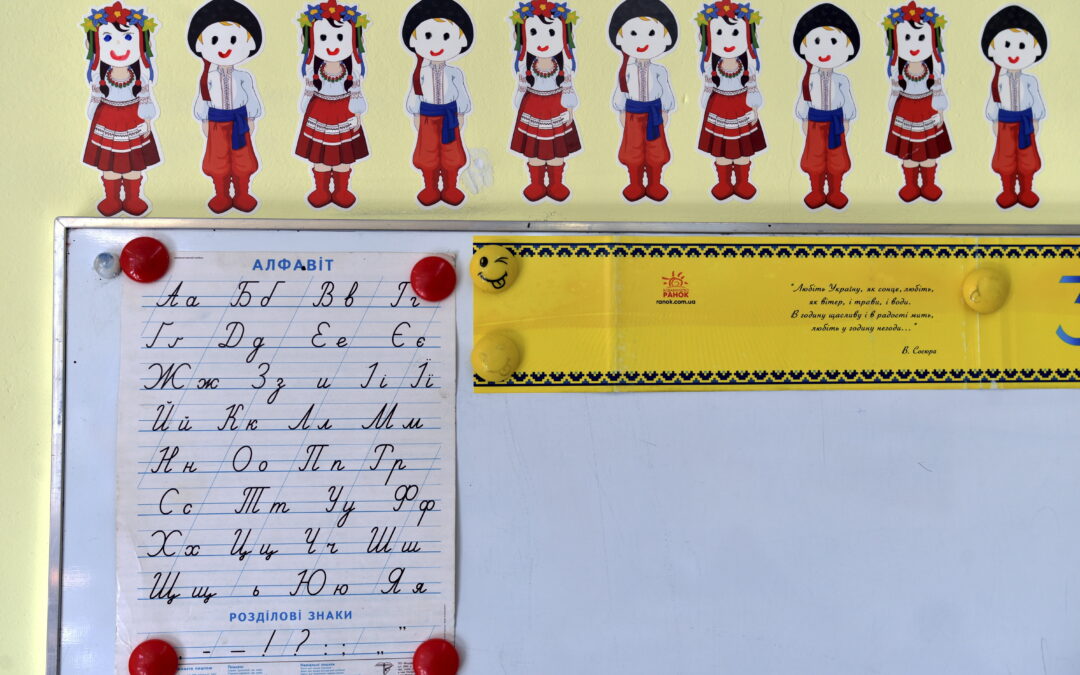

Although many of the Ukrainian pupils who have already joined Polish schools are attending normal classes, the education ministry wants more special preparatory classes to be formed to cater for their needs.

These are “less stressful” and “the most flexible form”, especially for pupils who do not speak Polish, said Czarnek, quoted by Portal Samorządkowy, a local government information website.

Teaching children in this way does not mean a lack of integration, which can still take place in physical education and games as well as competitions, he added.

Noting that around 500 such classes have already been formed, Czarnek pointed out that they can be shared between schools within and even between districts. Financial instruments ensuring funds for their creation have also been prepared, he assured.

With schools already struggling to find enough staff, new regulations will allow former teachers collecting a bridging pension to return to work in these preparatory classes. Teachers will also be allowed to work additional overtime at their discretion and with the regional superintendent’s permission.

There are concerns, however, over whether teachers will be willing to work in such conditions. Sławomir Broniarz, president of the Polish Teachers’ Union points out that members of his profession were disgruntled by the effects of the controversial Polish Deal tax reform package.

“You just have to read online teachers’ forums to see teachers making it clear that it’s not worth it for them to work more…They have the feeling that for more effort the taxman will take it from their wallets,” he told Money.pl. “Now we hear: you want to earn more, you have to work more.”

Polish schools face a very difficult challenge, Broniarz adds. “We don’t know how many children will come to schools, we don’t know for how long. Teachers will also have to deal with the language barrier. I’m sure they’ll cope, but it will take a great effort.”

Local authorities are also seeking to recruit teachers from among the Ukrainian people who have arrived in Poland. The municipal employment office in Kraków received 150 applications within three days of creating a new database of vacancies for Ukrainian teachers, reports Gazeta Wyborcza.

Many are from people who were previously teaching in Ukraine. “These are very competent people who know several languages and have been working with children for many years,” said Tomasz Kobylański of Kraków’s education department.

Some applicants speak Polish, although the majority only know Ukrainian and/or Russian, he added. The city authorities are therefore planning language classes combined with a module preparing teachers for working in Polish education.

“We want to make use of the support of specialists who have previously organised the municipal Intercultural Assistants Academy scheme as well as schools’ competences in teaching Polish as a foreign language,” explained Anna Domańska, director of the education department.

Main image credit: Robert Robaszewski / Agencja Wyborcza.pl

Ben Koschalka is a translator, lecturer, and senior editor at Notes from Poland. Originally from Britain, he has lived in Kraków since 2005.