By Ben Koschalka

Today’s memory of the Warsaw Uprising has been strongly influenced by the work of Sylwester Braun, a member of Poland’s underground resistance who documented on film the dramatic and tragic events of the struggle against Nazi-German occupation.

The Warsaw Uprising, which began on 1 August 1944 and lasted for 63 days, was the largest single military operation by any European resistance movement in World War II. The Polish Home Army led the effort to liberate Warsaw as the occupying Nazi-German forces retreated from Poland, but they were not supported by the advancing Red Army, which halted outside the city, enabling the Germans to regroup and retaliate.

An estimated 16,000 members of the Polish resistance lost their lives and around 6,000 were seriously injured, while up to 200,000 Polish civilians were killed. The fighting also took its toll on Warsaw’s buildings, around a quarter of which were destroyed during the uprising, and many more by the German troops after the Polish forces surrendered. By the end of the war, 85% of the city had been reduced to rubble.

March of the “Brave Lads” unit in front of a Warsaw city centre printers, August 1944 (photo: Sylwester Braun/from the collections of the Warsaw Rising Museum)

Many of the photographs chronicling the uprising were taken by Sylwester Braun. Born in Warsaw in 1909, Braun was a surveyor by profession, working in the City Planning Bureau, but when war broke out in 1939 he photographed the siege of Warsaw on his Leica camera.

“My passion for photography began in childhood,” he recalled in a radio interview in 1996. “My father returned from travels to Egypt and showed me photographs, which I was captivated by. I took his camera and bunked off school to the Bielany Forest. When I got home I immediately bought everything I needed for a laboratory to develop photos. That’s how it started.”

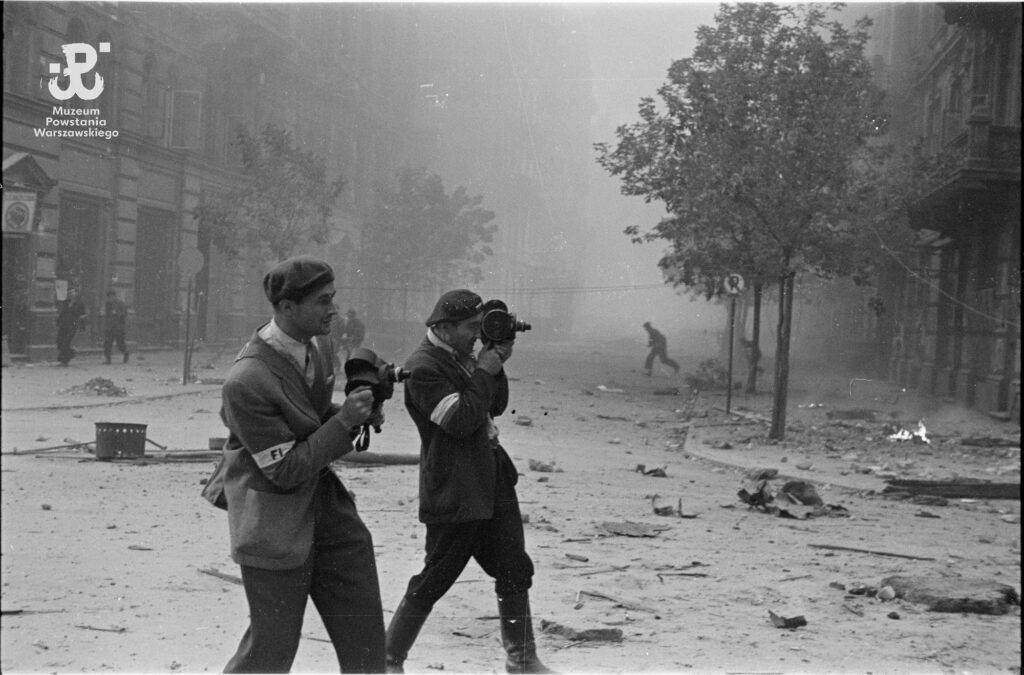

Cameramen Stefan Bagiński and Antoni Wawrzyniak in action, 2 September 1944 (photo: Sylwester Braun/from the collections of the Warsaw Rising Museum

Braun joined the underground in 1940, becoming a member of the Union of Armed Struggle, later the Home Army, and working as a photo reporter. In the first days of the uprising in 1944, he joined the photography section of the Bureau of Information and Propaganda.

“I was assigned to the ‘film vanguard’ [a documentary film and photo unit],” he later recalled. “There were weekly newspapers coming out and 80% of the photographs were mine. The most important thing was for them to be shown to the soldiers.”

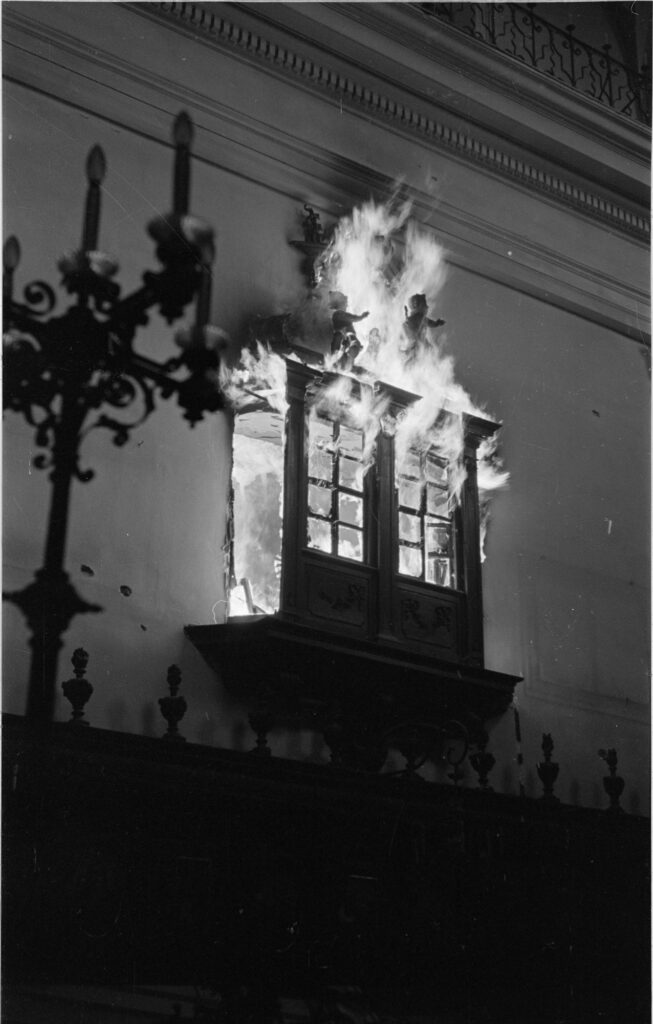

Battle for the Holy Cross Church on Krakowskie Przedmieście. Reclaimed by the insurgents in a spectacular success, the church’s facade was destroyed by German mines, and the occupiers later blew it up (photo: Sylwester Braun/public domain)

The field army reporter, codename “Kris”, took around 3,000 photographs during the uprising, but only half of them survived. He developed his pictures at home, despite limited resources, retaining ownership of his negatives.

The Holy Cross church on fire (photo: Sylwester Braun/public domain)

“I was never given any orders. All of Warsaw was my operating area. I tried to be everywhere I could, wherever something was happening – on the barricade and at the resource base, with the girls and the boys, in free Warsaw. While covering the city, I never asked anyone for names, aliases, or functions.”

“I made many copies of the pictures and distributed them to soldiers. Seeing the happiness on their faces made me feel satisfied.”

Braun (right) showing his photographs to soldiers during the uprising (photo: Eugeniusz Haneman/public domain)

Perhaps Braun’s most famous and iconic photograph (below) shows the moment on 28 August 1944 when a mortar shell hit the Prudential building, the 1930s Art Deco skyscraper that was Warsaw’s tallest building at the time. Braun later told of how he was sitting on the roof of his house at 28 Kopernika Street during the shelling, anticipating that the Prudential building would be a target.

The explosion caused by a 2-tonne mortar shell on the Prudential building in Warsaw (photo: Sylwester Braun/public domain)

“I saw a shell flying across the sky. I waited for the moment of impact. The explosion unfurled in complete silence, without any blast. Surprised, I took photographs. On the third one there was a bang, the sound and a terrible blast reached me, I even had to hold onto the chimney to stop myself from falling. I took around six photos then.”

Braun had been standing on the balcony at his house on the first day of the uprising when he observed the attack on Warsaw University.

Two women and a man flee with their dog from bombing across Napoleon Square (now Warsaw Uprising Square) (photo: Sylwester Braun/public domain)

“Kopernika Street was completely open, and the Germans could invade at any time…The next day, a barricade was erected in front of my house. The insurgents started to protect their inventory and organise the Powiśle district. They successfully captured the power station on Wybrzeże Kościuszkowskie. A Home Army division and the workers from the power station attacked the German crew on August 1 at 5 p.m.”

“The first days of the Uprising were successful, and we were given hope. Free Warsaw! Barricades are being erected. Insurgent troops are marching, singing songs. The insurgent press informs the world about the successes. We are collecting German weapons and ammunition; we are destroying German tanks. German flyers asking us to surrender only make people laugh.”

On 14 August, Braun photographed an armoured car captured by the insurgents.

The armoured German transporter captured by insurgents, photographed on Tamka Street, 14 August 1944 (photo: Sylwester Braun/public domain)

“The Germans most likely got lost. They were spotted by wounded in the insurgents hospital…as well as by people in apartments…They sounded the alarm. Whoever could rushed to the windows and started shooting. The falling rounds were mostly from pistols. The Germans, in a panic, rushed to escape, leaving their armoured car behind.”

Lt Wacław “Aspira” Jastrzębowski shows an SS man’s patches to Cpt Cyprian “Krybar” Odorkiewicz during an inspection on Okólnik Street following the capture of the armoured car (photo: Sylwester Braun/public domain)

He spoke admiringly of the women who “demonstrated the highest levels of sacrifice and courage. They stood by the barricades and manned the hospitals, filling the roles of courier, medic, and soldier. They travelled through the sewers, supported the resistance fighters on the front line of combat, carried the wounded, rescued the buried, and helped in the production of grenades and Molotov cocktails.”

A wedding during the uprising (photo: Sylwester Braun/public domain)

Braun said that if he were to choose a picture to symbolise the Uprising, it would be “A Child’s Prayer” (below).

“Insurgent cemeteries were set up throughout the small gardens in the courtyards of Mazowiecka Street. I was passing them as well on my escapades through the city. One day I saw a small girl genuflecting at a freshly dug grave. From far away I started taking pictures.”

A girl in a cemetery during the Warsaw Uprising (photo: Sylwester Braun/public domain)

After the uprising, Braun was sent to a displaced persons’ camp in Germany. He managed to escape and return to Warsaw, where he tried to retrieve his negatives, which he had buried in glass jars in a cellar.

“I dug up my films, it was an extremely harrowing moment,” he said in 1981, when donating his archives to the Museum of Warsaw. “My legs buckled, because I didn’t expect to get them back. The house was burnt down, the cellars dug up, but the place was undamaged.”

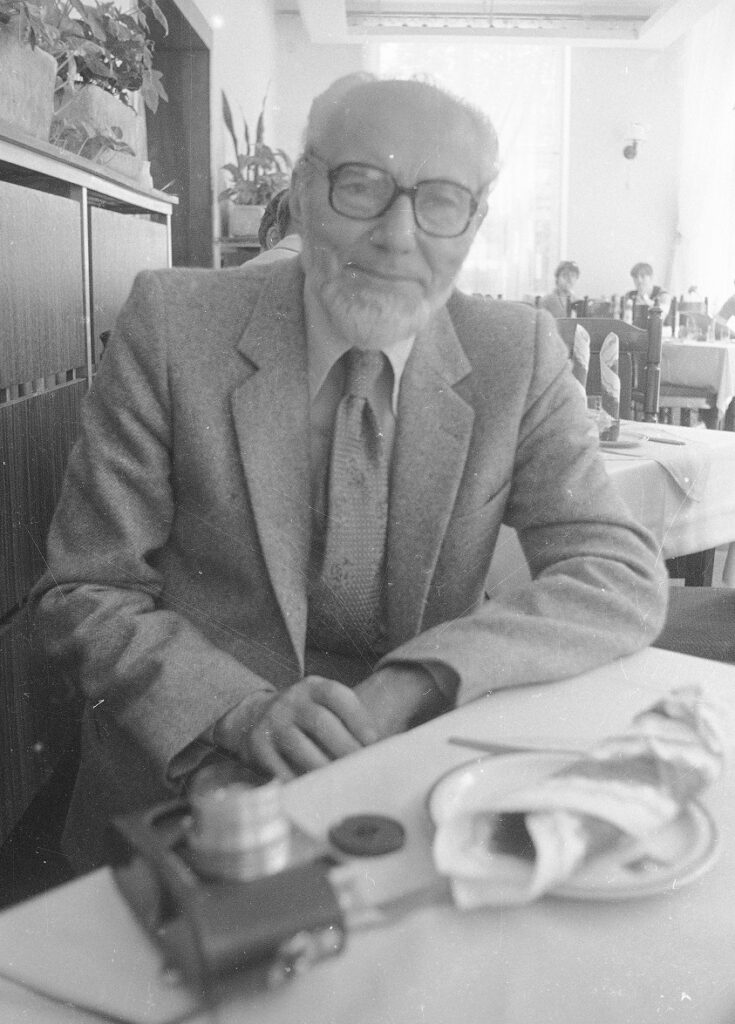

Sylwester “Kris” Braun in 1981 in Warsaw (photo: Włodzimierz Barchacz/Szukajwarchiwach)

After the war, Braun left Poland for Sweden, before emigrating to the United States. The first exhibition of his photographs in Poland took place in 1979 and a book of his photo-reportages was published four years later. He died in Warsaw in 1996.

Main image credit: Sylwester Braun/public domain

Ben Koschalka is a translator, lecturer, and senior editor at Notes from Poland. Originally from Britain, he has lived in Kraków since 2005.