By Juliette Bretan

With its illustrious theatres, revolving dance floors, and cutting-edge cinemas, the social world of interwar Warsaw was as glitzy as it gets. Already nicknamed the “Paris of the North”, Poland’s capital in the interwar period saw its traditional architecture complemented by the city’s first skyscrapers – including the Art Deco style Prudential building – neon lights, film studios, and expanding transport networks.

However, the outbreak of war brought this all to an abrupt halt. By 1945, around 85% of Warsaw lay in ruins. While the historic Old Town was faithfully rebuilt, much of the rest of the city was reimagined by the country’s new communist authorities, while cultural life was now strictly controlled.

Below we take a tour of some of the leading venues and institutions of a now-lost interwar Warsaw, as well as meeting some of the characters who populated this glittering cultural world.

Adria nightclub

Perhaps no insurance company was ever so glam. Built in the late 1920s as a home for Trieste-based RAS, number 10 Moniuszko Street – at the very heart of the Polish capital – became renowned for its swish modern design, with a granite and sandstone exterior, a main hall illuminated by sparkling chandeliers, a glass roof, plush furnishing and sculptures.

Adria director Franciszek Moszkowicz and a chimpanzee, New Year’s Ball, 1935

But beyond, spread across the ground floor and basement, was arguably the building’s most prominent feature – and the very height of the interwar social scene – the Adria nightclub.

With a winter café garden dripping in greenery, a slick American bar serving modern beverages like Manhattans and Coca Cola, a revolving dance floor (made from rubber, to avoid embarrassing slips), and even air conditioning, the venue was the first attempt to build a European-style venue in the Polish capital. It was a roaring success.

Press Ball at Cafe Adria, 1938

The enterprise was managed by entrepreneur Franciszek Moszkowicz, who – despite his own apparent aversion to the music and sounds of the modern era – transformed the venue into the heart of interwar Warsaw nightlife. Leading Polish artists and musicians and international stars regularly featured, alongside prominent social events including press balls, fashion balls and New Year’s Eve parties. The Adria also featured as a film-set for Polish films, including the 1933 film His Excellency, The Shop Assistant from 1933.

The building was one of few interwar-era locations to survive the war, despite being hit by a bomb in 1944, which lodged in the basement but – miraculously – did not explode. Whilst a newsclip from 1946 shows the building in ruins, with wires hanging loose and walls gaping, it was ultimately rebuilt, as a bank. A café was also reopened at the premises – but it closed in 2005, and nowadays, the building is a ghostly shell of its former heyday.

Mała Ziemiańska, the café to be seen at

With two richly decorated floors, bands of notable customers, literary excitement and exquisite pastries, the Mała Ziemiańska café was another legendary venue. It was sometimes standing room only at this central meeting place for leading figures and artists.

Wierzbowa Street, Warsaw, 1930s, with the neon signs of Adria, Ziemiańska and Oaza visible

Far from a mere coffeehouse, the café had a certain hierarchy, with several artistic groups congregating around their own specially designated tables. On the lower floor, prominent painters, including Tadeusz Gronowski, assembled at one table, while leading writers such as Witold Gombrowicz and Zuzanna Ginczanka met around another. Meanwhile, the upper floor became a temporary home for cabaret performances.

Mała Ziemiańska was particularly known as a haunt of the literati, reputedly the birthplace of numerous interwar literary successes. Above all, it was famous for its links to the Skamander poetry group (including Julian Tuwim, Antoni Słonimski, and Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz), who took up residence every afternoon on their prominent table. On occasion – and if permitted – other renowned figures and dignitaries, including cabaret writer and critic Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński and poet Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska, would also be allowed to join.

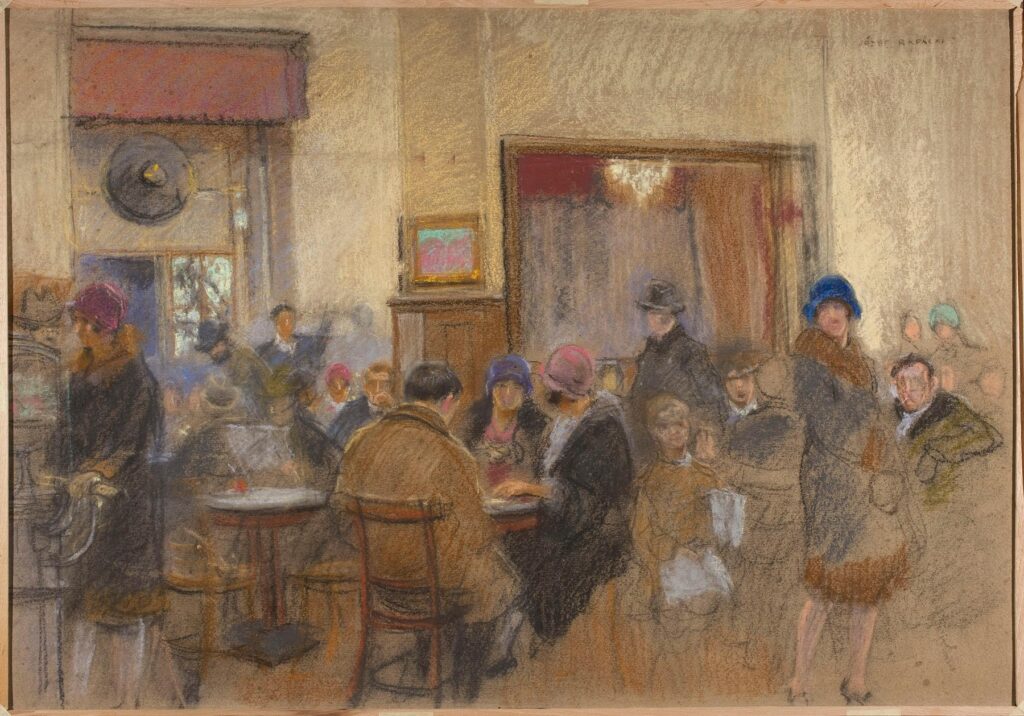

Inside Ziemiańska, a painting by Józef Rapacki, 1926 (Wikimedia/public domain)

The café was destroyed in the Warsaw Uprising, and was not rebuilt post-war. But its famous regulars, and distinct atmosphere, were immortalised in song, art and caricature in the interwar period, including in paintings by Józef Rapacki, and two meticulously detailed monochrome sketches of its myriad illustrious customers by Jerzy Jotes Szwajcer.

The silver screen

Cinemas took off in interwar Warsaw, screening home-grown and international productions. The era saw progress for Poland’s own film industry – the first sound picture, The Morality of Mrs Dulska, came in 1930, recorded at the studios of Syrena Record, Poland’s first recording company. Other movies were filmed abroad, whilst Polish film stars also gained international renown.

Constitution Day celebrations at a packed Colosseum cinema on Nowy Świat, 1934

There were at least 60 cinemas in Warsaw by the mid-1930s. One leading venue was the Atlantic, which boasted comfortable and functional interiors and all mod cons, including acoustic Celotex ceilings. As well as screening international movies and newsreels from around the world, it was also the first cinema in Warsaw capable of screening sound films. Its opening was attended by Polish dignitaries, including Prezydent Ignacy Mościcki and Marshal Józef Piłsudski.

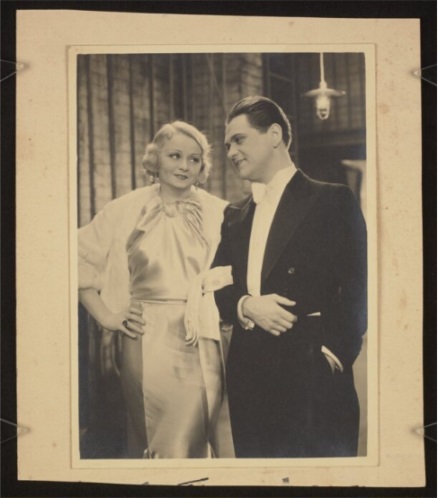

Maria Chmurkowska and Eugeniusz Bodo in the 1934 film Love, Cherish, Respect (source: Polana.pl/public domain)

The Atlantic survived the war mostly unscathed, and continued screening films through the communist era – under a distinctive blue neon sign. It is still in operation today – Warsaw’s oldest continuously operating cinema.

Hotels and fine dining

Entrance to the Bristol Hotel, 1930s

One of the best-known venues offering luxurious interiors and fine dining was the Bristol Hotel, which opened in 1909, and saw endless notable Polish and international guests – including the singer Jan Kiepura, who performed from the balcony.

Across Krakowskie Przedmieście was the Europejski, a 19th-century hotel with particularly opulent interiors. The building soon became famous for its dazzling parties, renowned visitors, and delicious food – immortalised in Bolesław Prus’s novel The Doll – and its reputation continued through the early 20th century, as the venue hosted fashion balls and events.

Polish White Cross carnival ball, 1937

A 1933 foxtrot, “Nikodem”, offers a snapshot of social life at the hotel, detailing a roster of interwar Polish (and international) celebrities such as the film director and actor Eugeniusz Bodo (pictured above).

Meanwhile, a little further west in the city was the Oaza restaurant, renowned for its gourmet fare, prominent performers, and rooms glistening in colour and folk designs. Close to the National Theatre, the restaurant’s patrons would often visit after a play for French cuisine washed down with liqueurs, cognac, or champagne.

Dancing at the Oaza restaurant

Of course, the Oaza especially catered for the affluent: in programmes, adverts for the latest cars, styles, fashions and fads feature alongside portraits of visiting European dancers. The venue was even home to a hairdresser, open day and night – even on Sundays.

Qui Pro Quo cabaret

Like many European metropolises of the time, Warsaw was home to numerous cabaret and revue stages hosting a wide variety of acts – from literary satires to spicy dancing, and everything in between. The cabaret world was so prominent that some shows even continued performing after the German invasion of September 1939, amid bombings and devastation.

Perhaps the most famous interwar cabaret was Qui Pro Quo, a cosy venue hidden in the bowels of the glass-covered Luxenburg Gallery at 29 Senatorska Street.

After its opening in 1919, the cabaret quickly became known for its high-quality sketches – which parodied everyday life, society and politics – and which were often written by leading literary figures, including Tuwim, Konrad Tom and Marian Hemar (later one of the main exponents of Polish culture in post-war London).

Performers on stage at Qui Pro Quo, including Mieczysław Fogg (top row, second right), 1929

The venue also became a breeding ground for Polish performance talent. Several of the most renowned stars of the era, such as Hanka Ordonówna, Mieczysław Fogg, and Zula Pogorzelska, began their careers on its stage. It was also home to revue and ballet performances by dancers who studied under Polish choreographer Tacjanna Wysocka.

Below the stage, the modern sounds of the 20th century, from jazz to tango, could be heard from the orchestra pit – which had been specially built atop a layer of Clicquot Club bottles to improve acoustics.

With its beloved performers, artists, musicians and writers, Qui Pro Quo became known as the “dear old shack” among Warsaw residents. But the cabaret was not to last. After several financial catastrophes, the doors finally closed in 1931 – although the spirit of the theatre lived on in several other venues across Warsaw throughout the 1930s.

The war ultimately brought an end to the Warsaw cabaret world – even the Luxenburg Gallery was destroyed in 1944, and never rebuilt.

Morskie Oko revue theatre

At the heart of the city centre, situated opposite the National Philharmonic and positively glowing with neon signage, Morskie Oko was another legendary venue.

Morskie Oko theatre, 1928

A contrast to the literary prowess of Qui Pro Quo, the theatre became particularly known for musical success and extravagant visual spectacle, with many performances modelled on revue shows across Europe. But far from just a Polish Casino de Paris, Morskie Oko was also deeply embedded in Varsovian life, with the titles of several shows referring to the capital.

At the helm was the indefatigable poet and lyricist Andrzej Włast, who became known as the “King of Trash” for his ability to write one sentimental hit after another (at breakneck speed, too – according to one urban legend, he could write the lyrics to a song in between sips of coffee). Many popular songs first heard in Morskie Oko shows subsequently became interwar classics.

Jewels of Warsaw revue at Morskie Oko Theatre, 1928

The theatre also attracted attention for its trailblazing acts: Włast frequently visited Paris for inspiration, bringing new trends to Warsaw for the first time – including modern dances, extravagant costuming and staging, and novel theatrical techniques, with actors performing among the guests’ tables.

But following the economic crisis, the theatre closed in 1933 – and its location was subsequently wiped off the map as a result of the war. Throughout the 1930s, Włast continued his cabaret successes in other venues across the city. But following the outbreak of war, he was ultimately imprisoned in the Warsaw ghetto, where he eventually died.

Fat Josek’s

A far cry from the opulence and glamour of the other venues mentioned above, Fat Josek’s – as it was affectionately known – was a 24-hour dive on Gnojna Street, run by Józef Ładowski.

With stuffy and rather unsanitary interiors, Fat Josek’s might have appeared an unlikely interwar social hub. But whilst the restaurant was mostly known as a meeting place for the Warsaw underworld, as well as pimps and prostitutes, in the early hours, it was also a prized venue for often inebriated high-society guests such as government officials, leading actors, and the city’s most prosperous residents.

Ładowski ran the venue with an iron fist – and thanks to his elite connections, he was able to evade any efforts by the police to have the venue shut down. Fat Josek’s became such a prominent feature of the cityscape that the restaurant was ultimately immortalised in a now-classic song, the 1934 “Bal u starego Joska”, where endless dancing and partying is haunted by spectres of darkness, danger and death.

Ładowski died in 1932, and Gnojna Street itself disappeared from the Warsaw map following the war.

All images unless stated: www.szukajwarchiwach.gov.pl (public domain)

Juliette Bretan is a freelance journalist covering Polish and Eastern European current affairs and culture. Her work has featured on the BBC World Service, and in CityMetric, The Independent, Ozy, New Eastern Europe and Culture.pl.