By Wojciech Kość

Maksymilian Zaręba is waiting for rain.

He is a young farmer with 120 hectares of rapeseed, wheat, triticale, rye, pea, and beetroot near the town of Pułtusk, around 60 kilometres north of Warsaw.

“There was 1 millimetre rainfall yesterday and not a drop for three weeks before that,” Zaręba told Notes from Poland on Tuesday. “That is very bad.”

On the lighter soils that he tends, rapeseed is already beginning to wither, he says.

Weather forecasts are not encouraging. The 16-day forecast for the Pułtusk area by Poland’s meteorological service IMGW-PIB says “light rain” might come only on 23 April, and then again on 28-29 April.

“This is one of the worst situations in the history of hydrological measurements in the country, which have been made for over a hundred years,” IMGW-PIB’s spokesman told broadcaster TVN24. Of 500 river-measuring stations, 42 have recorded levels below the norm. Last year, the figure was ten.

Luckily, temperatures are expected to hover just above 10 degrees throughout most of the month, at least sparing Zaręba accelerated evaporation of whatever little humidity is left in the ground – which is very little recently.

Climate change and water mismanagement driving drought

Zaręba is not alone in worrying about Poland getting ever drier. Across the country, farmers look up to the sky for weeks on end to find the same picture of mostly cloudless skies from which no rain is going to fall.

Poland has long been battling droughts. Last year, which was Poland’s hottest on record, the Vistula River reached its lowest-ever water level in Warsaw, dropping to 33 centimetres. As the country becomes warmer because of climate change, the problem is growing ever bigger and more complex.

Total rainfall in Poland has remained at a similar level to when winters were long and snowy and dry periods intertwined with wet ones, says Sebastian Szklarek, an ecologist at the Polish Academy of Sciences (PAN).

“The average annual rainfall of 550-600 millimetres per square metre tends to be concentrated over shorter periods of time, making it more difficult to retain water. Most flows quickly into rivers and further to the sea,” Szklarek says.

This situation is made worse by mismanagement of water and of the resources that could keep it in the ground.

“Having drained everything for years, we’re only speeding up the runoff,” says Szymon Malinowski, an atmospheric physicist at the University of Warsaw.

“Cold periods without snow cover prevent rebuilding of water resources. We remove groves, balks and mid-field afforestation for the purposes of large-scale agriculture. We concrete and seal off large areas in cities. No wonder that less and less rainfall can feed nature and agriculture,” Malinowski explains.

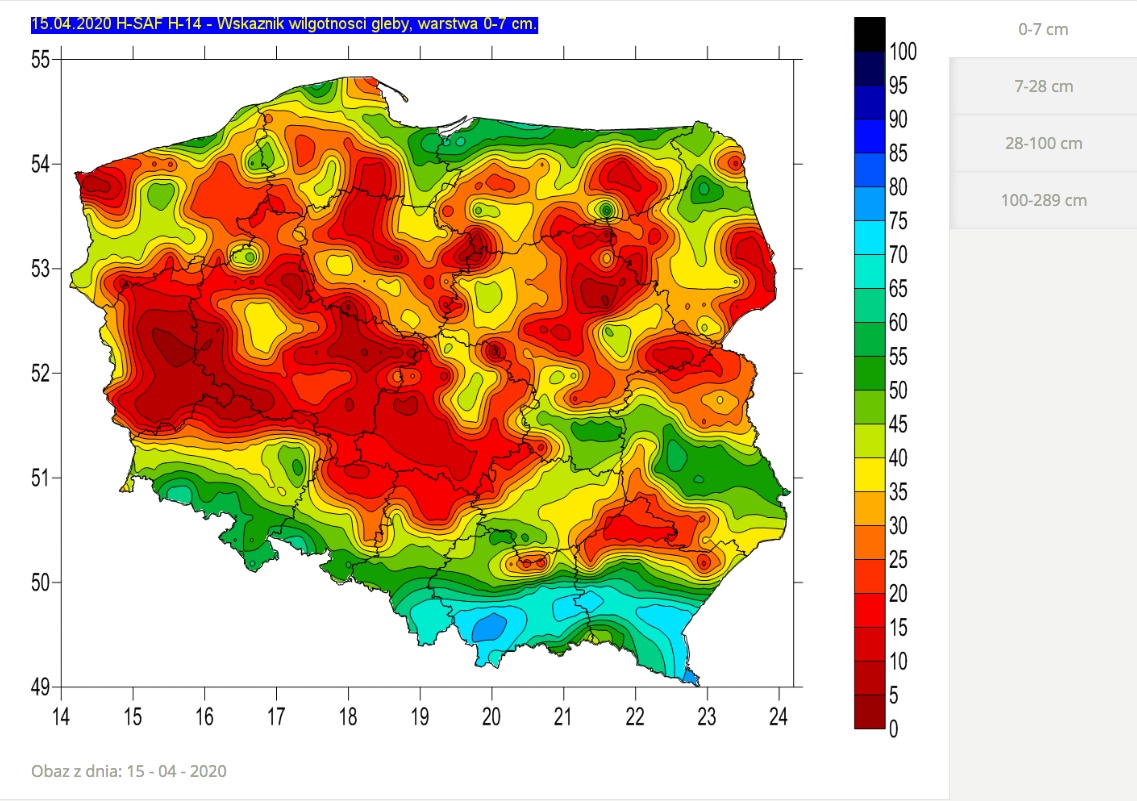

Daily satellite data showing soil humidity gathered by IMGW-PIB and Wody Polskie, Poland’s state-owned manager of the country’s waters, have recently shown large swathes of land – particularly in the centre and the west of the country – where humidity drops below 5%.

That is an issue for farmers like Zaręba. He says dry soil hampers the effectiveness of fertilisers. Going a little deeper, the situation is only a little better, with data showing that moisture does not exceed 30% in most of the country.

A map showing Poland’s soil humidity on 15 April. Most of Poland was below 30%, which indicates water deficit. Earlier this month, some areas were at 0%, a highly unusual and worrying occurrence in spring. (Source: Polish Institute of Meteorology and Water Management – National Research Institute)

As well as lower crop yields, the parched soil also increases the risk of forest fires. It is only April, yet there have been days this month when State Forests, the state-owned forest management company, put nearly the entire forest cover under red alert, meaning “high forest fire danger”.

Potential for rising prices food and energy prices

While these concerns are long term, what makes the situation even more troubling this year is that the drought will exacerbate the economic and social crisis that is already being created by the COVID-19 outbreak.

As well as the potential for rising food costs, electricity and water prices are also likely to go up for consumers, who have already been hit with some of the world’s highest inflation over recent months.

“In the longer term, there will be more and more water shortages for the power industry,” says Malinowski. “And then we can expect problems with meeting water demand in cities and from households.”

The latter already happened in June last year, when local authorities in Skierniewice, a town of some 50,000 people in central Poland, imposed limits on water use for households after demand soared amidst a heat wave.

The energy sector, with some of its installations dependent on cooling their power-generating systems with river water, is also uneasy. It has grappled with a heat and water crisis already. In August 2015, Poland’s power grid operator, PSE, imposed limits on energy consumption for industry after temperatures soared above 30 degrees, depressing water levels in rivers countrywide.

At a critical moment, utilities turning off capacity – because they could not cool generation systems – nearly eliminated the reserves needed to ensure the power system could work.

This year, that appears an unlikely scenario, as the coronavirus epidemic is more than likely to ravage the economy and therefore depress energy use. But the problem remains largely unsolved without a countrywide effort to keep water from just flushing down the rivers to the Baltic.

“We need to keep rainfall as close as possible to where it landed. Build small retention ponds, deregulate rivers to slow down their flow, and restore melioration systems so that they don’t just drain but also keep water,” says Szklarek.

“The problem with evaporation and precipitation will get worse if we don’t change the way water is managed so as to retain it in the environment. Otherwise there will be no water to feed crops and they will dry up. Next, forests will start burning,” adds Malinowski.

Back on his farm, Zaręba, too, is aware of the need to adapt. One way of reducing water use is no-till farming, which, he says, is becoming a method of choice for more and more farmers, even if they are still in the minority.

“It’s complicated because you need to take care of crop rotation, which is a problem in Poland, where the majority of crops are cereals,” said Zaręba, who is growing increasingly worried about his rapeseed. He says no-till farming can only solve so many problems if there is so little rain.

“I have around a month to decide if I want to get rid of rapeseed and plant corn instead. That’s about all I can do.”

Main image credit: Jakub Orzechowski/Agencja Gazeta