Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Alicja Ptak

When Donald Tusk’s government came to power, it promised to accelerate Poland’s move away from reliance on coal. But, after a year in office, the ruling coalition has failed to enact a single law that would significantly advance the energy transition.

Poland will this year spend more money subsidising its coal mining industry than Taylor Swift earned from ticket sales during the whole of her record-breaking Eras Tour, pointed out Polish energy analyst Jakub Wiech last month.

The figures are close – 9 billion zloty (€2.17 billion) of subsidies for Polish coal versus $2.07 billion (8.59 billion zloty) earned by the American pop superstar – but both represent eye-watering sums.

Mili Państwo, Taylor Swift pobiła rekord sprzedaży biletów na trasę koncertową – za Eras Tour zarobiła 2 077 618 725 dolarów. Słownie: ponad dwa miliardy dolarów; a więc ok. 8 mld złotych.

Pomimo tego Taylor Swift i tak nie byłaby w stanie utrzymać polskiego górnictwa węgla…

— Jakub Wiech (@jakubwiech) December 9, 2024

The Polish government’s large outlay on coal, up from 7 billion zloty (€1.69 billion) in 2024, is particularly surprising given that, prior to entering office, it committed to accelerating the country’s energy transition away from fossil fuels.

The cost of mining coal in Poland is among the highest in the world, at around 820 zloty per tonne of coal produced. By contrast, the figure is 160 zloty per tonne in the United States.

The higher costs in Poland relate to, among other things, challenging geological conditions, depleted mines and declining deposit quality. They mean that Polish mines make a loss of around 300 zloty per tonne extracted – hence the need for government subsidies.

The ruling coalition’s decision to bolster support for fossil fuels has thus raised eyebrows, given the high cost of coal and the need for energy diversification in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Google, Amazon, Mercedes and Ikea have appealed to Poland’s prime minister and parliament to support the development of green energy.

Otherwise, "the Polish economy is in danger of losing its competitiveness and attractiveness", they warn https://t.co/ytVcdwwiT1

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 21, 2023

Equally striking is the government’s broader lack of progress in advancing other elements of the energy transition.

That is despite Prime Minister Donald Tusk himself admitting that Poland’s high energy prices pose a risk to its economic competitiveness and prior warnings from international businesses that the lack of green energy could reduce future investment in the country.

“Not a priority”

Before taking office, the coalition signed an agreement that included commitments to “accelerate the green energy transition”, including by “increasing the share of renewable energy sources in electricity production” and “modernising and expanding transmission and distribution networks”.

However, progress on those fronts has been limited. After more than a year in office, the government has failed to enact a single law that would significantly move forward any of those energy commitments.

“The [energy] transition is not a priority for this government. It shows,” Aleksandra Gawlikowska-Fyk, director of the power sector programme at the Forum Energii think tank, tells Notes from Poland.

Michał Smoleń, head of the energy and climate research programme at Instrat, another think tank, agrees that the government has made insufficient progress. But he also praises it for being more open to collaboration with energy experts than the previous Law and Justice (PiS) administration was.

“After this first year, it is difficult to speak of any major achievements, but it is possible to speak of some things moving cautiously in the right direction,” he tells Notes from Poland.

The undying attachment to coal

As part of the coalition agreement, the government also promised a “fair transition” for energy workers, including those employed in the coal industry, that would take into account their financial security.

So far, the coalition has failed to make any progress with that pledge, despite it being impossible to escape the fact that moving away from fossil fuels will involve the mining sector undergoing major reform.

Poland extracts approximately 50 million tonnes of hard coal annually, more than ten times less than the US. Despite this, Poland’s coal mining industry employs about 74,000 people – around two-thirds more than the 45,000 employed in the US.

This translates to around 11,700 tonnes of coal extracted annually per employee in the US compared to just 675 tonnes per Polish worker.

“So, when one wonders where the 19 million zloty per day we spend subsidising the mining industry goes, the answer is simple: jobs,” wrote Wiech, who is editor-in-chief of energy news service Energetyka24, in his abovementioned post.

The Polish mining profession has historically wielded significant political influence, often shaping government policies through powerful trade unions. This month, thousands of people joined a protest organised by miners and energy workers in Warsaw against plans to shut down coal-fired power plants.

Thousands of people joined a protest organised by miners in Warsaw against plans to shut down coal-fired power plants.

They accused the government of threatening their livelihoods in favour of the EU's green policies https://t.co/iWzQBq58k5

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) January 10, 2025

Although this resistance from miners is understandable – their jobs are at stake – it is hampering change. Experts had hoped that the new government would take a stronger stance on reforming the sector, rather than kicking the can down the road.

“The transition also involves tough challenges, and the future of coal is one of them,” says Smoleń. “I worry that there may be, once again, the temptation to postpone making the coal plan more realistic, perhaps even until the next parliamentary term, which would be deeply problematic.”

Affordable energy for households and businesses

One of the most significant consequences of Poland’s delayed green transition is the high cost of electricity, driven by the need to sustain an unprofitable mining industry and the rising emissions expenses under the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS).

That prompted the coalition to previously pledge low energy prices for households and businesses, based on healthy competition mechanisms and clear market rules.

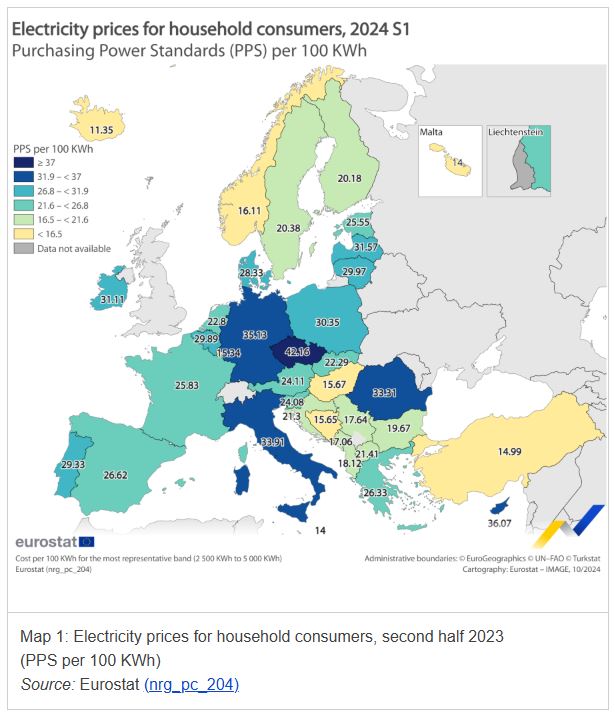

During the first half of 2024, however, Polish households faced the seventh highest energy prices in the EU in purchasing power standards (PPS). In the second half of the year, the cost of electricity rose even further following a partial unfreezing of prices by the government.

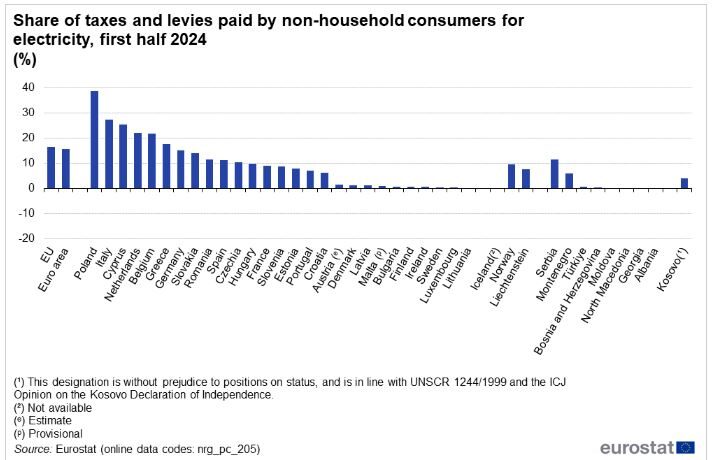

Eurostat data reveal that when buying electricity in the first half of 2024, Polish households bore the EU’s highest relative share of taxes and levies, which accounted for 49.6% of the total price. Those charges include VAT, but the cost of carbon dioxide (CO2) emission certificates also contributes to that figure.

To mitigate the impact of high electricity costs on households, the government last year extended part of the previously introduced electricity price freezes until the end of September 2025.

That decision was criticised by experts. Gawlikowska-Fyk points out that it diverts attention from addressing the root causes of high energy prices. “It also redirects funds that could otherwise be used for investment,” she notes.

The climate ministry, however, defends the policy. “Our goal is to ensure that every family has access to energy at an acceptable price, sufficient for normal functioning,” the ministry stated in response to questions from Notes from Poland.

The ministry added that, alongside efforts to control energy prices, the government is actively working to build a greener energy mix, highlighting ongoing discussions in the Polish parliament regarding an onshore wind bill.

Renewables and wind energy delays

The coalition agreement included a pledge to “work together to increase the share of renewable energy sources in electricity generation” and cited the untapped potential of wind, solar and biogas.

To help achieve this, the climate ministry has made attempts to loosen the law that determines the distance from buildings at which wind farms can be built.

A plan by Poland's incoming ruling coalition to make it easier to build wind turbines has been criticised by the outgoing government and some experts.

They claim it would allow expropriation of land for turbines, which could also be built closer to homes https://t.co/rtHXQ2DuXY

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 1, 2023

This change, long recommended by experts, aims to further unlock Poland’s onshore wind power capabilities, which were stifled under the former PiS administration’s so-called “10H rule” – scrapped in 2023 – forbidding the construction of wind farms where there are buildings within a distance of ten times the height of the turbine.

Early attempts to enact change faced criticism for proposing overly lenient regulations and were abandoned. A subsequent attempt at reform was attached to a controversial energy price freeze bill, which prompted a significant fall in the share price of state energy giant Orlen and was rejected by parliament.

Last September, the ministry finally proposed a revised plan to reduce the minimum distance of wind farms from buildings from 700 to 500 metres. The bill has yet to be approved. The ministry hopes for a vote on it this month, but has already missed several self-imposed deadlines, meaning that reform is likely to be further delayed.

“We would have liked it to have been signed off a long time ago,” Smoleń adds. “But it is indeed a step in the right direction that responds to the single biggest transition problem we have at the moment. This is a low-hanging apple.”

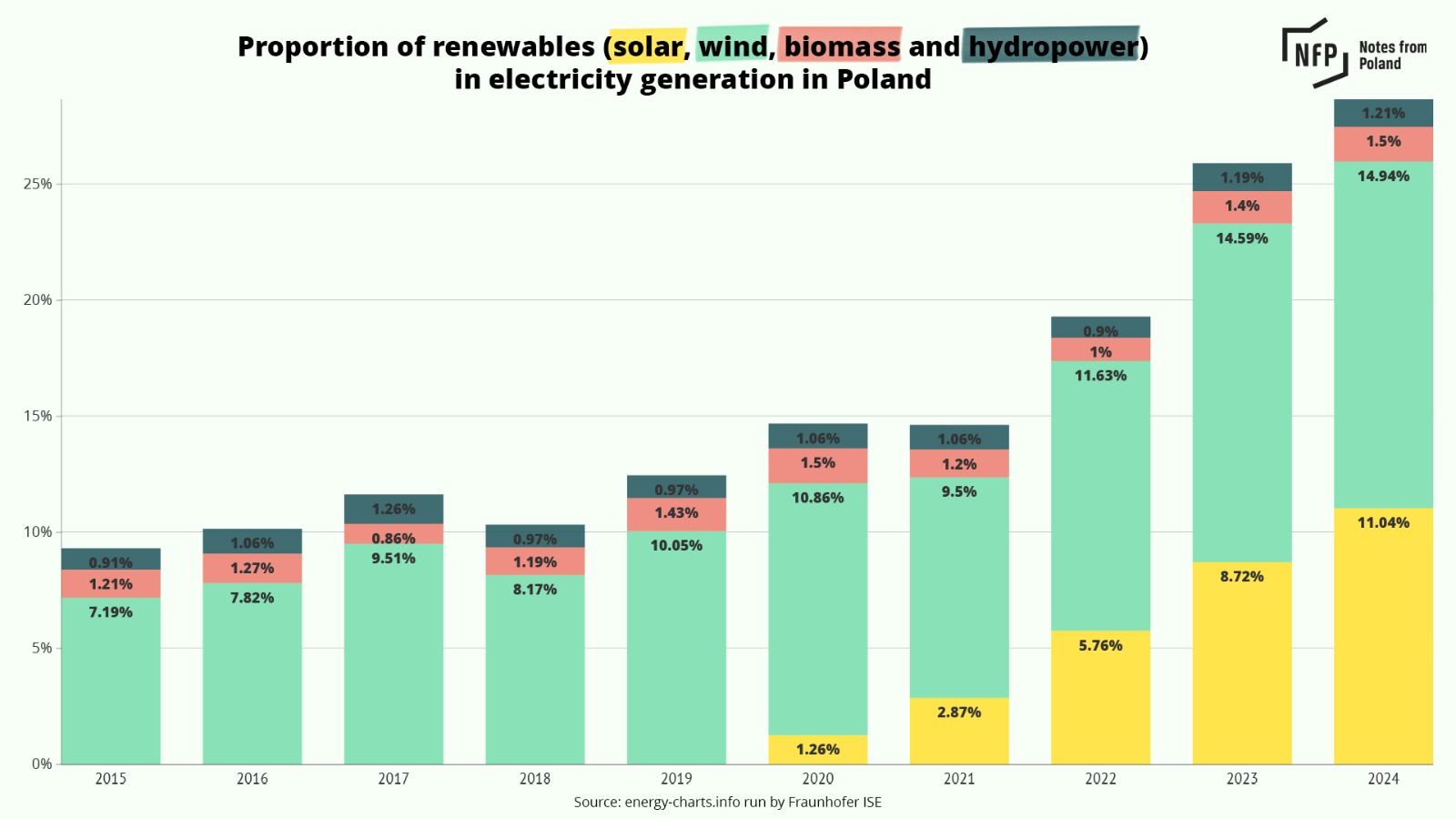

The use of renewables has, however, continued to grow despite the government’s inaction. Last year, they accounted for over 29% of Poland’s electricity, up from 26% a year earlier. Coal, meanwhile, produced almost 57% of power in 2024, down from 64% in 2023.

The shift has been driven by solar power, with subsidy programmes launched under PiS propelling solar’s share of electricity from 1.26% in 2020 to nearly 11% in 2024.

An outdated power grid

Although the rapid growth of Poland’s renewable energy capacity in recent years represents progress towards clean energy, it has also highlighted a critical issue: an outdated power grid struggling to manage an increasingly complex system.

This was a driving factor behind the coalition’s promise to modernise and expand energy transmission and distribution networks, although to date, little has been done to realise that aim.

Last September, the climate ministry announced that around 70 billion zloty (€16 billion) from the EU’s post-pandemic recovery funds would be allocated to the energy transition, including grid modernisation, via preferential loans.

Polish state energy giant Orlen has secured an €800m loan from the @EIB to modernise electricity distribution networks as part of Poland’s green transition.

The money will be used to expand renewable energy connections and introduce smart grid technology https://t.co/hCn8LJHQoR

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) November 13, 2024

Additionally, Polish state energy giant Orlen in November secured a 3.5 billion zloty (€800 million) loan from the European Investment Bank (EIB) to upgrade its electricity distribution networks.

However, Poland’s power grid operator, PSE, has instructed renewable electricity producers to halt production on certain days due to low demand and high output, which risks overloading the grid.

It has also increasingly refused to connect new energy sources to the grid, including those from prosumers – households that produce as well as consume electricity through micro-installations, such as solar panels – thus disincentivising the production of cleaner energy.

Poland produced a record amount of wind power on 25 December, when it met 44% of national demand.

However, the grid struggled to cope, resulting in turbines having to be turned off and electricity transferred to Germany under an emergency procedure https://t.co/vYFlVyvxKE

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 28, 2023

The nuclear option

As well as renewables, a key element in Poland’s plans to move from coal towards low- and zero-emissions power sources is nuclear, which the former PiS government envisaged producing almost a quarter of the country’s electricity by 2040.

However, at the moment Poland does not have – and has never had – a nuclear plant. The Tusk administration has, despite some initial doubts, confirmed that it will move ahead with plans to develop the country’s first such power station.

In September, it outlined plans to provide billions in financing for the project, which were approved by the cabinet this month. However, they must still be confirmed by parliament and President Andrzej Duda.

Meanwhile, the government has already indicated that the project will be delayed, but Smoleń and Gawlikowska-Fyk remain sceptical about Poland’s ability to keep even to the newly suggested deadlines.

Poland's government has given final approval for plans to spend 60.2 billion zloty ($14.6 billion) on developing the country's first nuclear power plant.

For more, see our previous report: https://t.co/F0aqChP1G3 https://t.co/ZBYLzCaK4X

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) January 8, 2025

“Unfortunately, for the time being, I have no reason to be optimistic about the implementation of the nuclear programme,” Smoleń tells us. However, the analyst says that overall he is “relatively optimistic” about Poland’s energy transition.

Yet the government’s energy strategy seems to be stuck in a pattern of prioritising short-term fixes over long-term sustainability, which is threatening Poland’s environmental goals, energy security and economic competitiveness.

Without significant legislative movement toward the sustainable policies pledged in the coalition agreement, the country risks falling behind its European neighbours in the race for a greener future and threatening its own economic development.

The energy transition “is no longer a question of hope, but a question of the security of the electricity system”, warns Gawlikowska-Fyk.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Victor Gleim/Wikimedia Commons (under CC BY-SA 4.0), Unfortunately Named/Wikimedia Commons (under CC BY 3.0), Kancelaria Premiera/Krystian Maj and Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe. Collage created by Agata Pyka

Alicja Ptak is deputy editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland and a multimedia journalist. She has written for Clean Energy Wire and The Times, and she hosts her own podcast, The Warsaw Wire, on Poland’s economy and energy sector. She previously worked for Reuters.