By Filip Mazurczak

Many Poles are rightly proud that, during the Second World War, their nation never produced a collaborationist government and instead spawned one of the largest resistance movements in German-occupied Europe.

In recent years, however, historians have unearthed a growing body of evidence pointing to war crimes by the so-called Polish “Blue Police” during the occupation, in particular in relation to the Holocaust.

Yet such findings require nuance, and the Blue Police’s complicity must be examined in the context of the formation’s founding and functioning, its unpopularity among Polish society, and the Polish underground’s opposition to it.

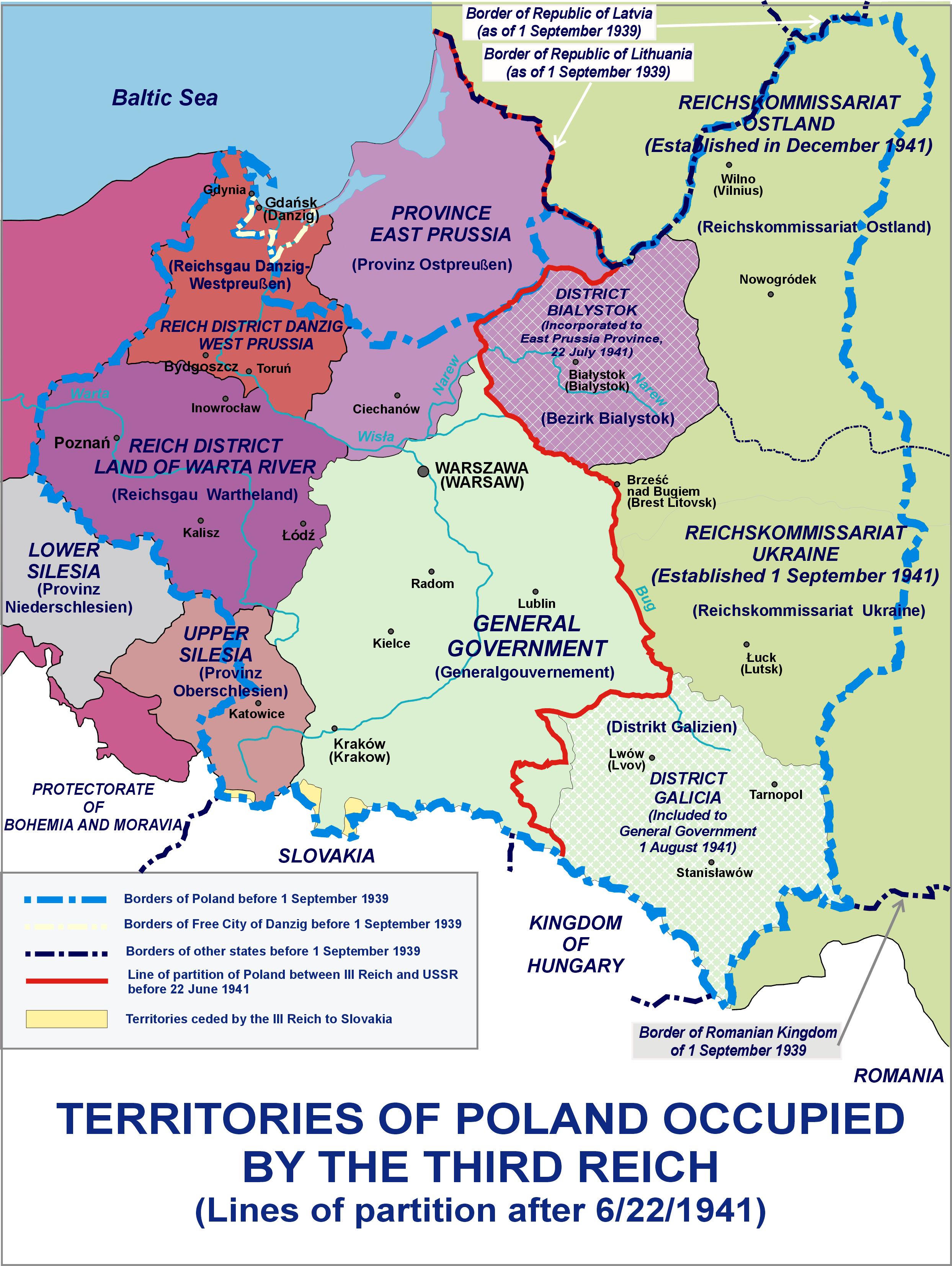

The structure of German-occupied Poland

On 1 September 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland from the west, while Hitler’s Soviet ally attacked from the east sixteen days later. For five weeks, the million-strong Polish army fought bravely, but was no match for the Wehrmacht. During the September campaign, 200,000 Polish citizens – mostly civilians – lost their lives.

The town that was the first to be attacked by Germany during the 1939 invasion of Poland has demanded war reparations.

Its resolution – the first of its kind by a local authority – has been welcomed by the government official overseeing reparations claims https://t.co/lpp07q61ZS

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) August 30, 2023

Having conquered Poland, the Third Reich directly incorporated the western Polish territories of Pomerania, Silesia, Greater Poland and the Łódź region.

Meanwhile, a colonial entity known as the General Government (GG), headed by Hitler’s lawyer Hans Frank and headquartered in Kraków, was formed in the remaining occupied areas.

The GG was divided into four districts (Warsaw, Kraków, Radom, Lublin), with a fourth, Galicia, later created in previously Soviet-occupied Polish territories that were conquered by the Germans during Operation Barbarossa.

In the annexed territories, Poles and Jews were deported to the GG to make room for German colonists, while up to 100,000 educated Poles – professors, physicians, lawyers, teachers, clergymen – were shot or deported to concentration camps, where most died.

While anti-Jewish measures were immediately introduced in the GG, the mass murder of Polish Jews would begin in 1942.

A “land without a Quisling”

Unlike in most other nations conquered by Hitler, there was never a puppet government in Poland.

While some historians, including Norman Davies in his influential God’s Playground, have attributed this to the fact that in the Nazi ideology the Poles were “subhuman” Slavs unworthy of sitting at the same table as the Nordic “master race”, such an argument is unconvincing when we consider the fact that Bulgaria was an ally of the Reich, while collaborationist regimes existed in Slavic lands like the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Slovakia and Croatia.

Meanwhile, many Ukrainians, furious at the Soviets for the genocidal famine of 1932-1933 and hoping the Germans would create a Ukrainian state independent of Poland and Russia, joined collaborationist organisations like the SS-Galizien, the Ukrainian auxiliary police or the Nachtigall Battalion.

A Polish government minister has launched a bid to extradite the 98-year-old Ukrainian Canadian who received a standing ovation in Canada’s parliament.

Yaroslav Hunka served in a German Nazi unit that was involved in war crimes against Poles and Jews https://t.co/dQOHwWngpc

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) September 26, 2023

Even some Soviet military commanders like Andrey Vlasov and Bronislav Kaminski defected to the German side and led formations of Soviet soldiers fighting alongside the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS, respectively. Kaminski’s RONA brigade was involved in mass murder during the crushing of the 1944 Warsaw Uprising.

Moreover, early in the war, the Germans approached prewar Polish prime ministers like Kazimierz Bartel (later killed during the German massacre of Lwów professors) and Wincenty Witos with offers to become a Polish Laval or Quisling, yet both declined.

Likewise, attempts at creating a Polish SS division flopped. In the Tatra Mountain region of Podhale, the Germans claimed that the Górale, or Polish highlanders, were a separate race superior to other Poles and tried to create a Góral SS division, whose members would work as concentration camp guards.

Across Podhale, a promotional campaign promised recruits greater food rations and amnesty for their family members incarcerated in concentration and forced labour camps.

However. only a couple of hundred signed up, and when the Germans took them to camps to perform genocidal duties, the Górale got into brawls with Ukrainian guards or deserted; subsequently, the formation was disbanded.

The formation of the Blue Police

Although attempts to foster high-level political collaboration in occupied Poland were unsuccessful, in the GG the Germans employed low-level collaborators.

These included village elders and firefighters, while the Baudienst, young Poles conscripted into construction work, were compelled to serve the occupiers.

That the Baudienst were employed to kill Jews after the Germans tried to numb their consciences with vodka is attested by the fact that in a 2 November 1942 letter to Hans Frank, Kraków Archbishop Adam Sapieha protested the use of these Poles in anti-Jewish actions.

Inspection at a Baudienst construction site near Sanok.

Apart from such institutionalised forms of collaboration, there were also plenty of Gestapo agents in the GG. Throughout the GG, bands of Poles dubbed szmalcownicy made a living off blackmailing Jews; historian Gunnar S. Paulsson estimates that in Warsaw alone, between three and four thousand Poles were engaged in such practices.

Meanwhile, General Stefan Grot-Rowecki, the commander of the Home Army, the main branch of the Polish resistance, was arrested and deported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where he was shot on Heinrich’s Himmler’s personal orders after the Warsaw Uprising had broken out; the Germans identified Grot-Rowecki after he had been denounced by a fellow Pole.

Today marks the 77th anniversary of the beginning of the Warsaw Uprising.

Memory of the struggle has been strongly influenced by the work of Sylwester Braun, a member of Poland's underground resistance who photographed the dramatic and tragic eventshttps://t.co/OprNr0Y0vX

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) August 1, 2021

However, the largest and most controversial collaborationist formation was the Blue Police, officially known as the Polish Police of the General Government.

According to historian Henryk Ćwięk, the Germans were satisfied with their collaboration with Czech police in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, created by the Third Reich half a year before the conquest of Poland, so they decided to employ a similar strategy in the GG.

Immediately after the conquest of Poland had been completed, all Slavic Polish policemen (mostly ethnic Poles, along with some Ukrainians and Belarusians; meanwhile, Jewish officers were dismissed) had to report to occupation authorities by 30 October 1939; failing to do so was punishable by death or deportation to a concentration camp.

On 17 December, Frank issued a declaration officially establishing the Polish Police of the General Government.

The Jews who worked as police in the WWII ghettos have one of the most difficult legacies in the history of the Holocaust, having been both collaborators and victims.

We speak with historian Katarzyna Person about her award-winning research on the subject https://t.co/oPGQIIETs7

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) July 16, 2020

The Blue Police functioned in four of the five districts of the GG (in the Galicia district, the Ukrainian auxiliary police played an analogous role; there was no equivalent organisation in the annexed territories).

Throughout the war, up to 18,000 officers served in the Blue Police. While desertion was punished by execution or deportation to camps, the German authorities also eventually accepted recruits, luring them with greater food rations (in the GG, Germans were allotted 2,613 calories a day, while Ukrainians received 1,000, Poles 699, and Jews just 184).

Local police forces and the Holocaust

Many of the Blue Police’s duties were related to keeping law and order, such as arresting petty criminals and directing traffic. Yet the Germans also employed them as auxiliaries in violent repressions against Jews, Roma and Polish partisans.

In 1992, Raul Hilberg, the doyen of Holocaust history, wrote:

“Of all the native police forces in occupied Eastern Europe, those of Poland were least involved in anti-Jewish actions…They could not join the Germans in major operations against Jews or Polish resistors, lest they be considered traitors by virtually every Polish onlooker.”

However, more recently, Polish historians have found new evidence that makes Hilberg’s evaluation sound excessively optimistic. In works such as Night Without End: The Fate of Jews in German-Occupied Poland, researchers, most notably Jan Grabowski and Barbara Engelking, have pointed to several forms of participation by the Blue Police in the Holocaust.

According to their study of nine rural counties in the GG and Białystok District, two in three Jews who sought refuge among Gentiles did not survive to the end of the war; the “Blue” Police was a major reason for this.

The Polish police force had a key role in the Nazi Final Solution, explosive new research shows https://t.co/stOTqcm5I5

— Haaretz.com (@haaretzcom) June 11, 2020

Particularly in the rural GG, the “Blues” guarded ghettos during deportation actions to prevent Jews from fleeing. During such actions, they searched ghetto cellars and attics for hidden Jews.

After the destruction of the ghettos, meanwhile, the police searched for fugitive Jews hiding among the Gentile population. Some were handed over to the Gestapo, but there were plenty of cases in which the “Blues” took the initiative and shot Jews they discovered themselves.

Emanuel Ringelblum, the chronicler of the Warsaw Ghetto, wrote in his 1943 essay Polish-Jewish Relations During the Second World War:

“It is difficult to estimate the number of Jews in this country who fell victim thanks to the Blue Police; it must certainly amount to tens of thousands of those who managed to escape the German slaughterers.”

That the Blue Police were engaged in anti-Jewish actions was common knowledge in Poland. As early as 1947, Stanisław Rembek published his novel Wyrok na Franciszka Kłosa (The Sentence Against Franciszek Kłosa), adapted into a 2000 film by Andrzej Wajda. The eponymous antagonist is a Blue policeman shot by the Polish underground for killing Jews and Polish partisans.

Meanwhile, in 1990 Adam Hempel published his scholarly work Pogrobowcy Klęski. Rzecz o policji granatowej w GG 1939 – 1945 (The Undertakers of the Defeat: On the Blue Police in the GG, 1939-1945). One of the book’s chapters deals with the Blue Police’s crimes against Jews.

However, until Grabowski’s 2020 study on the Blues and the Holocaust, Hempel’s work was the only monograph on the Blue Police. In Poland, the topic was treated as a taboo, challenging the national myth of universal resistance to the Third Reich, and received relatively little attention from historians until recently.

The education minister says he will not approve funding for academics who "offend Poles and the Polish nation, the greatest victim of WWII".

Last week a Holocaust scholar from a state-funded institute said Poles did little to help Jews during the war https://t.co/MmuP3AAnul

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) April 25, 2023

The Blue Police was by no means unique. Across Europe, the Germans employed local police forces in the Holocaust. In Vichy France, French police and gendarmes rounded up and deported 76,000 Jews to Auschwitz-Birkenau and French-run internment camps like Drancy (in the latter alone, 3,000 died of poor conditions) with nary a German in sight.

In German satellites like Hungary, Slovakia and Romania, local authorities with minimal to no German supervision rounded up hundreds of thousands of Jews, shooting some on the spot and loading the rest onto cattle cars headed for Auschwitz-Birkenau. Meanwhile, in the Galicia district of the GG and the Reichskommissariat Ukraine, the Ukrainian auxiliary police shot numerous Jews.

The Polish reaction

Certainly, the documented participation of the Blue Police in the Holocaust challenges the view that the Poles were immune to treason amidst the terrors of the war. Yet some additional context must be provided.

In the essay quoted above, Ringelblum writes that:

“The Polish Police [was] commonly called the Blue or uniformed police in order to avoid using the term ‘Polish.'”

If Hilberg was too optimistic about the Blue Police’s lack of involvement in the Holocaust, he was right that most Poles considered them to be traitors. In the GG, many Poles were ashamed that their countrymen were serving the Germans; the very term “Blue Police” attests to this. After all, the colour of policemen’s uniforms was the same as in the prewar period.

Many non-Jewish Poles hated the “Blues” because they themselves were their victims. The “Blues” routinely handed over ethnic Poles who tried to avoid deportations to Germany for forced labour, illegally raised and slaughtered livestock, owned firearms (a capital offense in the GG), or were active in the underground resistance. The Blue Police also cooperated in the pacification of many Polish villages.

Furthermore, the Polish Home Army executed many Blue Policemen for their crimes against Polish Jews.

In September this year, the Vatican beatified Józef and Wiktoria Ulma and their seven children as martyrs. The Ulmas, Catholic peasants in the village of Markowa who hid two Jewish families, a capital offense in the GG, were denounced to the Gestapo by Włodzimierz Leś, a Blue Policemen.

After the Ulmas and the Jews they assisted were killed by the Germans, the Home Army shot Leś in retaliation. In postwar Poland, courts sentenced many Blue policemen and other collaborators to death.

Over 30,000 pilgrims and Poland’s most senior officials attended a ceremony to mark the beatification – a step on the path to possible sainthood – of a Polish family murdered by the Nazi German occupiers for hiding Jews in their home during the Holocaust https://t.co/QhsQBG51R3

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) September 10, 2023

A further factor that complicates an evaluation of the Blue Police is that, as well as the fact its members were in effect forced by the Germans to serve, many were also agents of the Home Army. According to Adam Hempel, perhaps as many as one third cooperated with the underground.

One notable example is Marian Kozielewski, the brother of Jan Karski, the famous Home Army courier who personally informed the incredulous and apathetic leaders of Britain and the United States about the Holocaust.

Kozielewski, commandant of the Blue Police in Warsaw, cooperated with the Home Army and along with his brother co-authored reports for the Polish government-in-exile on the fate of Polish Jews under German and Soviet rule. Along with 69 of his subordinates also engaged in underground work, Kozielewski was deported to Auschwitz in 1940.

A room at the European Parliament has been named after Witold Pilecki, the Polish underground officer who deliberately had himself imprisoned at Auschwitz during WWII to gather intelligence and organise resistance at the camp https://t.co/bQHkJRDbp3

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 16, 2023

The complicity of the Polish Blue Police in German Nazi crimes is indisputable, and challenges the common narrative among Poles that their predecessors refused to collaborate.

Yet evaluation of their legacy cannot be divorced from the complicated and horrific context of German terror, the contempt with which other Poles looked upon the Blue Police, and the many acts of Polish resistance in the war.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Map credit: Lonio17/Wikimedia Commons (under CC BY-SA 4.0)