By Stanley Bill

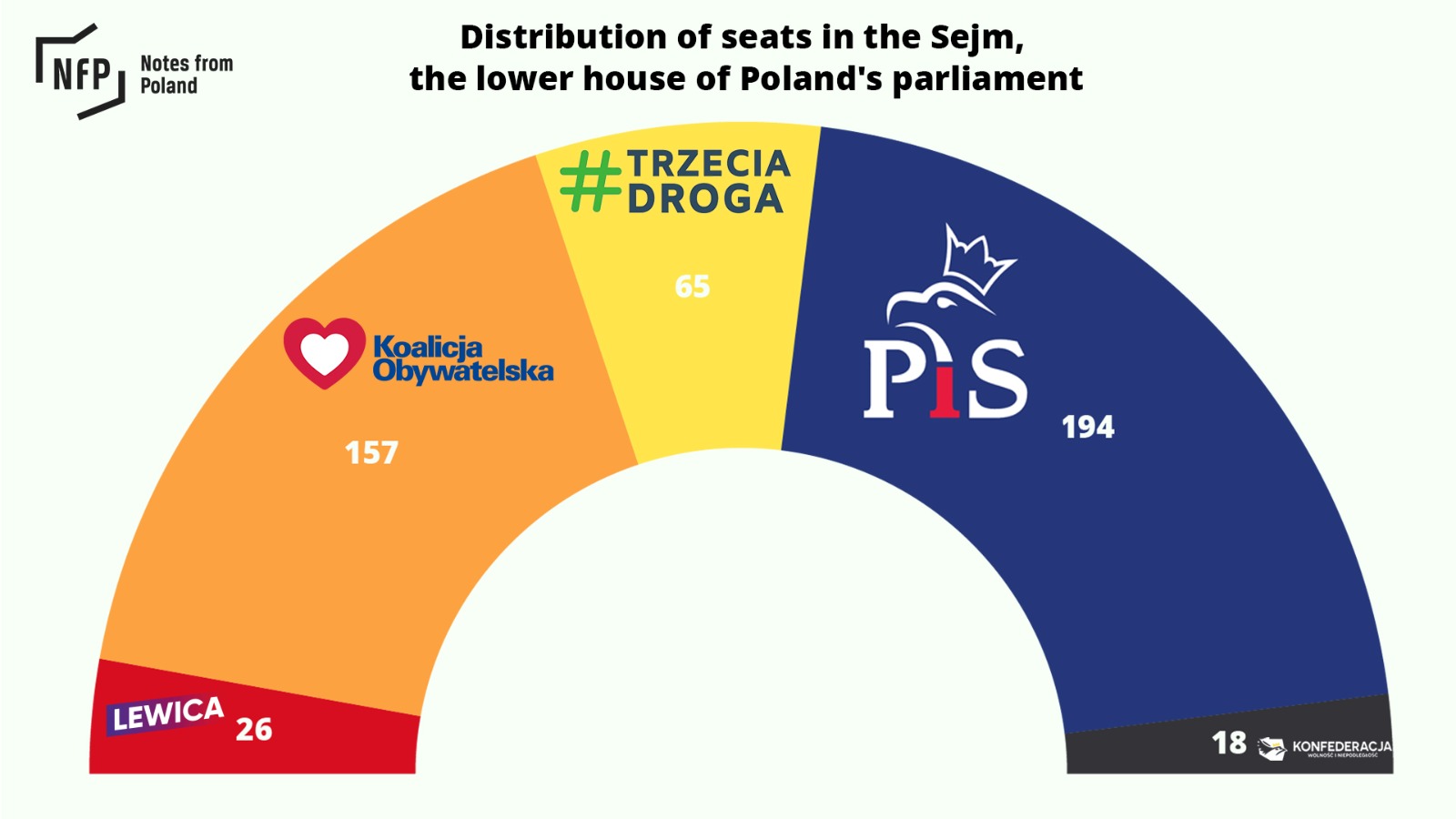

Poland’s recent parliamentary election was a virtual plebiscite on the Law and Justice (PiS)-led government. Massive turnout of 74% carried a coalition of opposition parties to an overall majority of 248 seats in the 460-seat parliament, though PiS remains the largest party. PiS is set to lose power, but remains a potent political force.

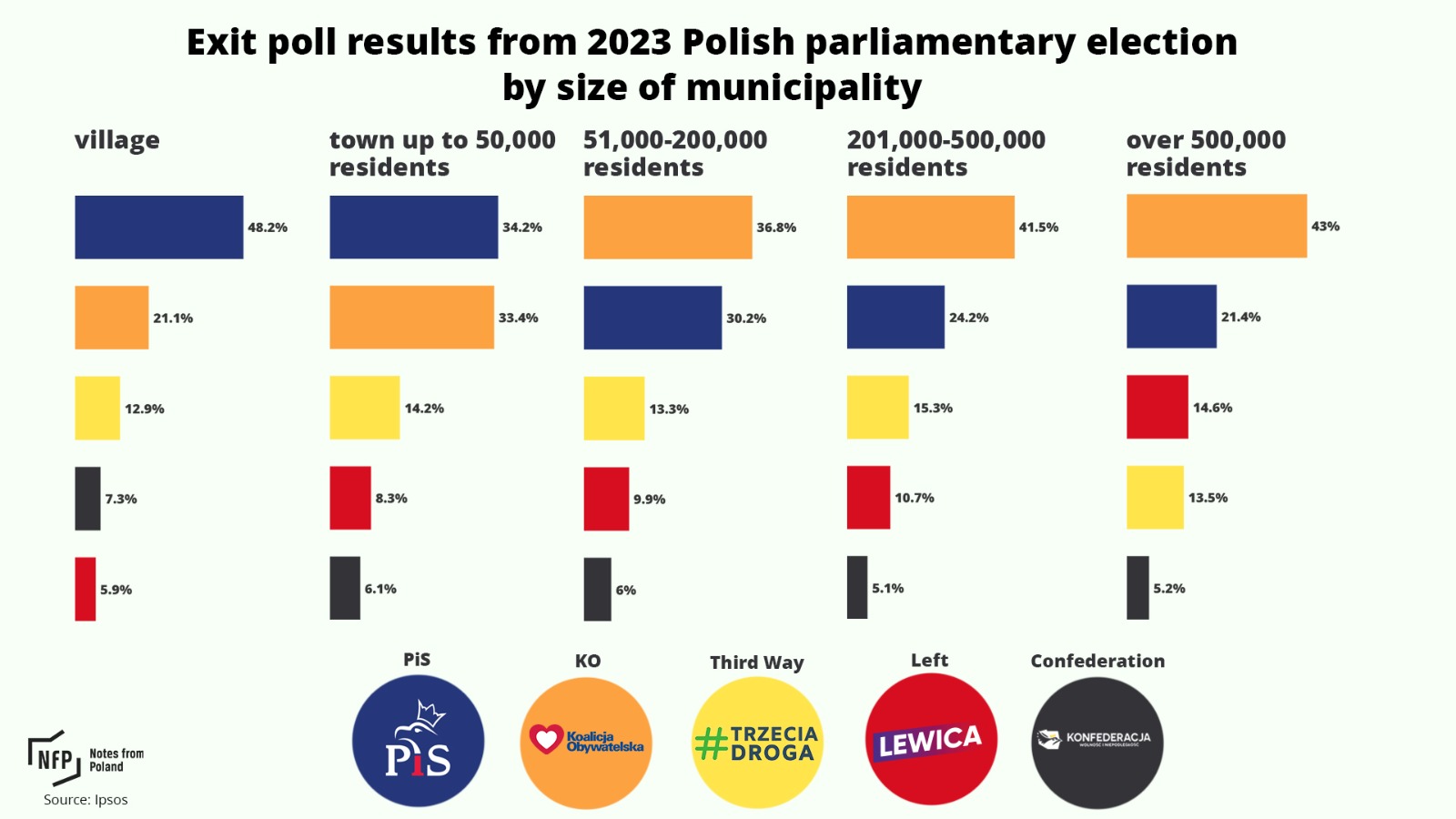

The opposition’s victory rested in part on huge turnout in their metropolitan strongholds and among young people, who voted overwhelmingly against PiS. Yet a deeper look shows that the ruling party lost this election in its heartland of villages and small towns.

Overall, PiS’s vote share fell from 43.59% in 2019 to 35.38% in 2023 – a drop of 8.21 percentage points.

A comparison of official voting data from the National Electoral Commission (PKW) for those two years shows that a huge 5.85 percentage points of this decline was in heartland districts of up to 20,000 inhabitants, representing a staggering 71% of the party’s overall losses. In villages alone, the party lost 3.12 percentage points, constituting 38% of its overall losses.

Poland’s decision to ban Ukrainian grain – angering both Kyiv and Brussels – highlighted how important rural votes are for the ruling party as it bids for re-election.

Rural areas account for 40% of Poland's population, one of the highest levels in the EU https://t.co/QI2WRqUHaT

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) April 25, 2023

To be clear, PiS still won a lot more votes in these areas than any other party, but the extent of its dominance was significantly reduced. In villages, its vote share plummeted from 56% to 45% in official PKW data. These losses in its strongest territory were crucial to its diminished overall performance. In short, the party lost power precisely where it expected to win.

High turnout was part of the problem in the heartland too. In fact, turnout increased proportionally by much more in villages and small towns than in large cities, where it had always been high.

This should have helped PiS, as more voters came out in its core areas. Indeed, the party had mobilised state funds in the form of turnout bonuses precisely to boost the vote in districts of up to 20,000 inhabitants, at a potential cost of over PLN 1.5 billion. This campaign apparently succeeded but the effect hurt PiS instead of helping.

The government promised grants for rural housewives' clubs, brass bands and renovating fire stations if there was high turnout in small communities, which are traditionally more likely to vote for the ruling PiS party.

For more, see our report ⬇️ https://t.co/XPc6rayW3C

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 20, 2023

In the village, turnout rose by a massive 25% (compared with 13% in large cities), but PiS did not increase its own raw number of votes from 2019. The additional village voters – many of them probably in younger cohorts – seem mostly to have chosen opposition parties.

The largest opposition grouping, centrist liberal Civic Coalition (KO), took more than half of its total gains in the village, adding 1.71 percentage points to its share there (overall, it rose 3.3 percentage points from 27.4% to 30.7%).

The centre-right Third Way (Trzecia Droga) coalition, which includes the agrarian Polish People’s Party (PSL), also added 1.5 percentage points in the countryside, compared to PSL’s result in 2019, while far-right Confederation (Konfederacja) made all of its small gains there.

Increased turnout in small districts was also intertwined with another key factor: depopulation. The high turnout there reflected a larger voting proportion of a smaller number of potential voters.

Villages and small towns, especially in the east, have been dramatically affected by the wider ageing and shrinking of Poland’s population. Many Poles have left small districts, moving to large cities and the regions around them.

These demographic changes are fundamentally unfavourable to PiS, a party whose conservative redistributionism especially appeals to older, more traditional voters in less economically developed parts of the country.

As party leader Jarosław Kaczyński himself observed after the election, “the structure of the electorate has changed… if we [PiS] are to triumph again, we must do so in a different Poland.”

Eastern Poland has seen its population decline while suburbs are attracting more residents, new census data shows

Poland's total population fell 1.2% from 2011 to 2021 (to 38.04 million) while Wrocław has overtaken Łódź as the country's third largest city https://t.co/xH3lxN0OeW

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) September 21, 2022

Many older voters have passed away since 2019, especially given the impact of the Covid pandemic, during which Poland had one of Europe’s highest excess death rates. Younger ones, including in villages and small towns, have come out against PiS’s policies and perhaps above all against their perceived monopoly on power.

In the countryside, specific factors motivating anti-PiS voters may have included high inflation, controversies over grain from Ukraine, local corruption, and an unpopular animal rights bill proposed in 2020.

Ironically, the success of PiS’s redistributive policies could also have pulled some voters in regional areas out of the party’s target socioeconomic groups, creating a small aspiring middle class less supportive of redistribution.

Poland is no longer a low-wage country, says ruling party leader Jarosław Kaczyński, who points to @OECD data showing that Polish average earnings are just behind Japan's https://t.co/b5dZh691Gb

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) November 13, 2022

Finally, the anger that clearly galvanized many city voters after PiS’s use of a captured court ruling to restrict abortion rights in 2020 may also have motivated voters in villages and small towns.

Opinion polls show as many as 48% of village inhabitants favouring widened access to abortion, and 55% in small towns. In appeasing ultra-conservative supporters and key allies in the church, PiS overreached on the abortion issue, potentially alienating a majority of voters even in some of its heartland districts.

After the election, PiS is far from a spent force. The opposition coalition faces potential delays to the formation of its government from PiS-affiliated president Andrzej Duda and obstruction of its legislative agenda by presidential veto.

We answer 12 questions about Poland's new government, including:

1. How will it be formed?

2. Will it be stable?

3. How will it tackle rule of law and abortion?

4. Can it unlock EU funds?

5. Will it face presidential vetoes?Read our full analysis here⬇️https://t.co/oLK33waftV

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 23, 2023

The coalition may also prove unstable due to the wide range of competing ideological positions within it. A chaotic government will make it difficult for the coalition parties to maintain the level of mobilisation that helped them win, especially among their new village and small-town voters.

But PiS’s defeat in the plebiscite of this parliamentary election suggests that the centre of gravity of Polish society may be shifting against them. Support for the party in its heartland and the boost these regions gave to its overall vote share have declined, in part due to inexorable demographic trends.

PiS may indeed require new strategies for a “new Poland” if it is to return to power.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Jakub Wlodek / Agencja Wyborcza.pl

Stanley Bill is the founder and editor-at-large of Notes from Poland. He is also Professor of Polish Studies and Director of the Polish Studies Programme at the University of Cambridge. He has spent more than ten years living in Poland, mostly based in Kraków and Bielsko-Biała.

He is the Chair of the Board of the Notes from Poland Foundation.