By Jakub Wiech

As it absorbs a succession of smaller companies and increases international activity, Polish state oil giant Orlen has an opportunity to join the European elite. But this will come at a high price.

Front-page news

Shares in a refinery, filling stations and fuel depots – these are the assets transferred to Saudi Aramco, Hungarian company MOL and Polish capital group Unimot as part of the sale of the assets of the Polish oil firm Lotos, recently taken over by Orlen.

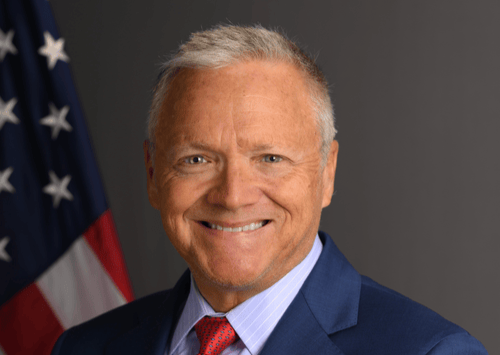

The acquirers were presented at a press conference in Warsaw last month by Daniel Obajtek, Płock-based Orlen’s CEO, thereby sealing the fate of the merger of Poland’s two largest fuel companies.

“This is a very important day for our economy and the economy of the entire region. Climate policy as well as pressure from regulators and the market demand transformation,” Obajtek told the assembled guests, noting that his company was currently at a critical moment of its merger.

The justification given by Orlen’s boss was not confined to the press conference. On 17 January, the front covers of most of the biggest Polish daily newspapers as well as the dozens of regional newspapers purchased by Orlen last year featured an advertorial interview with Obajtek.

The article presented the reasons for and benefits of the merger. Every publication came with the same photograph of the Orlen CEO. Some saw this is a herald of his alleged political ambitions; others as a willingness to attribute the process into which the company was throwing itself to one person.

ON SALE: Look at the front pages six Polish leading newspapers today, with a massive sponsored story on the Govt-controlled oil giant PKN Orlen on every single one of them.

That's what happens when the industry struggles for money & is ready to sell everything. (ht @AgaRucinska) pic.twitter.com/OXzuDYAEFK

— Jakub Krupa (@JakubKrupa) January 17, 2022

The need to put an end to the internal cannibalism on the fuel market by merging Orlen with Lotos had long been touted. Particularly loud noises were made among figures associated with the current United Right coalition government, led by the Law and Justice (PiS) party. The idea appeared on the political agenda when PiS party was first in power (2005-2007).

It is now being implemented by Obajtek, the most influential person in the current executive pack. It is mostly his determination and ambitions that remodelled the idea of taking over Lotos into a vision of building a multi-energy corporation competing in the top division of European companies.

To achieve this goal, under Obajtek’s leadership Orlen has taken over Energa (one of the largest electricity groups in Poland), Ruch (a press distributor with around 1,300 retail points), the Polska Press group (which controls 20 regional dailies as well as hundreds of smaller publications and news websites), and – in addition to Lotos – also wants to merge with PGNiG (the Polish gas market leader).

A costly deal

The key element in this whole process, however, was joining forces with the second largest Polish oil company, Lotos. The venture required the consent of the European Commission. This was given – albeit in the form of conditional approval – in July 2020. The commission gave the merger the green light as long as certain remedies were implemented, which meant the sale of some of Lotos’s assets.

For more on the merger between state-owned refiner PKN Orlen and rival Lotos Group, and how it fits the Polish government's plans for a "global energy syndicate", read our recent report: https://t.co/mABM4JIWag

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) September 28, 2020

Since this time, it has been clear that the union will be costly – not only for the company, but for the state too. Nonetheless, although the commission’s conditions have been known about for well over a year, many Polish journalists and commentators seemed surprised by Orlen’s agreement with Aramco, MOL and Unimot.

They focused above all on the agreement with MOL regarding the transfer of filling stations. The Polish company sold 417 Lotos stations to the Hungarian company, while itself buying 144 in Hungary and a further 41 in Slovakia from MOL.

But it was not what the deal involved, but who it was done with that was the subject of much commentary in Poland. Suspicion lingers around MOL as a company with structural links with Russia, since the Russian company Surgutneftegas purchased 21.1% of the Hungarian firm’s shares in 2009.

Although that stake was later bought by the Hungarian government in 2011, many journalists still look at MOL from the angle of its relations with Russian capital (perhaps the rather close energy links between Russia and Hungary also play some role).

Jeśli PiS naprawdę sprzedał stacje Lotosu węgierskiej firmie MOL, politycznie związanej z Moskwą, to znaczy, że Ład Kaczyńskiego jest bardziej rosyjski, niż sądzili najwięksi pesymiści.

— Donald Tusk (@donaldtusk) January 9, 2022

However, focusing on the trade in filling stations misses the point – from the perspective of Orlen’s or Lotos’s current activity, these are assets with practically no strategic importance.

They have – as an easily noticeable representation of the brand – a certain marketing significance, but in the enormous venture of a merger of two Polish oil companies, they play a small role.

At the other extreme of value are rights to use Lotos’s Gdańsk refinery. This infrastructure is the jewel in the crown of the new company – all thanks to the EFRA (Effective Refining) project taking place there, which permits advanced petroleum processing and production of high-margin fuels as well as petroleum coke.

The value of this project is 2.3 billion zloty (€500 million). Shares in the refinery are to fall to Saudi Aramco – which will be useful for embedding the Saudis in the Polish oil market. A parallel element of this process is a contract with Aramco for petroleum supplies to Poland, signed at the same time as the sale of assets.

Saudi Aramco’s agreement to supply almost half of Poland’s oil will give the world’s biggest crude exporter a stronger foothold in a region that Russian producers have long dominated, writes Bloomberg https://t.co/CiF4LPnVUM

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) January 13, 2022

The contract volume is estimated at between 200,000 to 337,000 barrels per day, meaning that it would meet almost 50% of the demand of the entire network of Orlen refineries, including those in the Czech Republic and Lithuania. From Poland’s perspective, this has considerable importance for achieving independence from Russian oil supplies.

Aramco is also to take on 100% of shares of Lotos SPV1 (which receives the assets of wholesale sales of Lotos fuels) as well as Lotos’s part of the Lotos-Air BP-Polska shares. With the latter transaction came the signing of a contract for supply of aviation fuel for a period of 15 years – the supplier will be PKN Orlen.

Meanwhile, the Polish Unimot Group will take over Lotos Terminale, a logistics operator with a network of nine fuel terminals producing asphalts in factories in Jasło and Czechowice-Dziedzice. This makes Unimot the third largest entity in Poland dealing with fuel storage.

Was it worth it?

Looking at the balance sheet from Orlen’s merger with Lotos, one might wonder whether it made financial sense for the company – and Poland too, since it is partly controlled by the state treasury.

An analysis of the package of assets that came under the control of other entities reveals that, although the energy giant and the Polish state lose control over certain strategically important facilities (especially part of the processing capacity of the Gdańsk refinery), in return it is building important relationships with partners that could provide support in realising long-term plans.

Orlen wants to be a match for Europe’s top multi-energy giants, such as Eni or OMV. This is an ambitious and also very difficult challenge, which can only be completed by maximising its own domestic potential and exploiting it fully to build influence in foreign markets.

Polish state oil giant Orlen has announced a €641 million plan to modernise and expand its refinery in Lithuania.

Poland's government say it will be "the largest investment in the history of Lithuania" and will bolster the region's energy security https://t.co/3BANpGLVik

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 12, 2021

From this point of view, the merger with Lotos seemed inevitable. The question remains, however, whether Orlen will manage to harness this potential.

Orlen’s turn towards foreign markets has been visible for some time. The company’s increased activity in the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Germany whetted the appetite for more.

Diving into the deep end of the European market, however, means that assets it already owns first need to be combined into a coherent, synchronised whole. This is where problems might arise.

Orlen as a company is supposed to play an important role in the process of Poland’s energy transformation. Its importance will only grow after taking control of PGNiG, as the coming years are sure to be marked by replacement of Poland’s coal capacity with gas.

Furthermore, it is necessary to preserve Energa’s electricity assets and an advanced programme of offshore wind farms, where Orlen’s company Baltic Power is operating. The issue of Orlen’s involvement in construction of small modular reactions (SMR), with the company working with Michał Sołowow’s Synthos, remains an open question. All this will take place under the conditions of an increasingly ambitious EU climate policy.

A government flagship

Orlen’s development will also depend on the role the company plays in Polish politics. The Płock giant is the flagship in a flotilla of treasury-controlled firms. It is Orlen’s revenue that PiS politicians point to when they want to boast of the managerial skills of the executive team introduced to state firms under their rule.

The government presents the company’s investments and takeovers as evidence of development – and these ventures will only grow in importance, as Daniel Obajtek’s company is to play a significant role in Poland’s energy transformation, propelling the offshore sector and building gas blocks.

There is also no lack of short-term activities demonstrating the company’s dexterity – during the first wave of the pandemic, it was Orlen that urgently organised production lines making hand sanitisers and began distributing them at its filling stations. Retailing at prices that compared favourably to the extremely expensive alternatives at the time, they sold out in no time.

Orlen is also a kind of instrument of international policy and a calling card for Poland abroad. The company’s Lithuanian branch is that country’s biggest taxpayer and a key employer. In the Czech Republic, meanwhile, Orlen Unipetrol is the only entity processing petroleum and one of the 10 biggest businesses.

Orlen’s filling stations in Central Europe, which until recently operated under various names (e.g. Star in Germany and Benzina in Slovakia), are gradually standardising their visual identification and adding the Polish company’s characteristic eagle to their brands.

Orlen has also advertised on Formula 1 racing cars with sponsorship of Robert Kubica’s crew. According to calculations, this generated brand exposure worth 110 million zloty (€24 million). All these characteristics make Orlen an important element of Polish international soft power.

Formula 1 team @alfaromeoracing will be called Alfa Romeo Racing ORLEN next season, with Polish state-controlled oil and gas firm @PKN_ORLEN becoming the team's title sponsor and Polish driver Robert Kubica becoming their test driver https://t.co/HbunrT8baa

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) January 1, 2020

All of this, however, adds to the challenges facing the company as a result of the planned mergers. To make it all a success, Orlen will need a long-term, consistent strategy and special organisational efforts.

The processes of merging the companies alone are a major trial of strength. It will also be essential to implement ambitious investment projects, which in some cases are absolutely pioneering in the Polish market, and to develop the international branches.

Dealing with this challenge will be a gauge showing whether such processes as Orlen’s merger with Lotos were genuinely beneficial.

Translated by Ben Koschalka. Main image credit: Dawid Zuchowicz / Agencja Wyborcza.pl