Poland is one of a number of European countries that are making “insufficient” efforts to tackle the problem of antisemitism, a US federal commission has found. It notes that antisemitic attitudes remain relatively widespread in Poland and that Polish Jewish leaders say the community does not feel safe.

The findings are presented in a report, Antisemitism in Europe, published by the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. USCIRF, whose members are appointed by the president and leaders of both political parties in Congress, monitors freedom of religion around the world.

The commission asked Jewish community leaders and government officials in 11 European countries about: the prevalence and nature of antisemitic attitudes and incidents; tolerance of antisemitism in public; and the actions taken by the authorities to counter and prevent antisemitism.

It found that in only one of those places, Norway, is the government undertaking actions “that meet the antisemitism challenges in the country”. In the remaining ten – including Poland, as well as the likes of France, Russia, Germany and the UK – “efforts seem insufficient”.

In its chapter on Poland, USCIRF notes that “recent debates over Holocaust history and restitution…unleashed unprecedented antisemitic commentary”. It quotes from a 2018 letter published by the Polish Jewish communal leadership, who “express[ed] outrage over the growing wave of intolerance, xenophobia, and antisemitism in Poland”.

“Polish Jews do not feel safe in Poland,” wrote the communal leaders. “We are no longer surprised when members of local councils, parliament, and other state officials contribute antisemitic speech to public discourse.”

While they noted that senior officials – including the president and prime minister – have condemned antisemitism, “these words ring empty…without strong supporting actions…We receive authorities’ inaction as tacit consent for hatred directed toward the Jewish community”.

Such concerns were heightened in 2018 by controversy over the Polish government passing a law criminalising false attribution of Holocaust crimes to Poland. The debate it provoked included a rise in anti-Jewish rhetoric in Poland and “the same issues persist at present,” found USCIRF, following its interviews with Polish Jewish leaders.

The report also cites a 2018 survey of Jews in 12 European countries by the EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA). It found that, in Poland, 32% of Jews said they had witnessed other Jews being insulted, harassed or physically attacked in the past 12 months. That was the highest figure for any country.

Poland also had the highest proportion of Jews (91%) saying that the government does not combat antisemitism effectively, and the second highest proportion (61%, behind only France on 77%) who said that antisemitism had “increased a lot in the country over the past five years”.

USCIRF also notes the results of a global survey of antisemitism, which found in 2019 that anti-Jewish attitudes were more common in Poland than any other country studied and had risen significantly since 2015. A separate study this year found one in five Poles saying “it is good that [the war] resulted in fewer Jews in Poland”.

In a separate annual report on religious freedom around the globe, also published this month, USCIRF notes that “antisemitism featured heavily in Poland’s presidential campaign” last year.

During the re-election bid of incumbent president Andrzej Duda, state television – which is under the influence of the ruling party – regularly broadcast news reports suggesting that Duda’s main opponent, Rafał Trzaskowski, was seeking to “fulfil Jewish demands” and working on behalf of a “powerful foreign lobby” linked to George Soros.

Following a complaint from the American Jewish Committee, Poland’s Media Ethics Council found that public TV’s broadcasts had “incited antisemitism and hatred against minorities”. Election observers from the OSCE noted that coverage of the election in state media was “charged with antisemitic undertones”.

USCIRF also found that the Polish government has no comprehensive plan for combatting antisemitism, and nor is contemporary antisemitism addressed in the school curriculum. However, it noted that there are optional state-funded educational programmes on antisemitism available to teachers.

The commission also reported that Jewish leaders in Poland expressed satisfaction at security measures in place at Jewish institutions, the costs of which are partially subsidised by the state.

Poland’s small Jewish community – which numbers 5,000, according to USCIRF – experiences little physical violence. In 2019, the chief rabbi, Michael Schudrich, told the Jerusalem Post that it was safe for a Jew to walk around in a yarmulke in Poland. “Can the same be said in Belgium and France?” he asked.

Poland is a safe place for Jews, says the chief rabbi.

'I call it the yarmulke test: Can you walk around safe with a yarmulke? It’s a crude measure of antisemitism, but in Warsaw and Krakow we have no problems. Can the same be said in Belgium and France?' https://t.co/OMdJUbJuEe

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 15, 2019

In 2018, the number of antisemitic incidents recorded by police in Poland reached 181, the highest level since a change in data collection methodology in 2015. It then dropped to 128 the following year.

However, “Jewish community leaders reported disappointment that the vast number of antisemitic criminal complaints were not prosecuted as antisemitic hate crimes”, USCIRF found.

Among its policy recommendations for Poland, USCIRF suggests more “clear and comprehensive” categorisation of antisemitic incidents, such as is done in the UK and France. In Poland, by contrast, 89% of antisemitic incidents recorded by police are categorised as “unspecified”, making the issue harder to deal with.

It also recommends that Poland and other countries each appoint a single “antisemitism coordinator” so that Jewish communities, governments and the international community have one authority to deal with.

Leading Polish officials have regularly condemned antisemitism, with President Duda saying that “there is no room for any form of prejudice, racism, xenophobia, antisemitism in Poland”. But they have also called for similar attention to be paid to prejudice against Poles and Christians.

Last year, just before International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said that, while “we have been fighting antisemitism around the world for decades, we are only just beginning the fight against anti-Polonism”.

He called for Poles and Jews to be united by their “common history and common suffering”, including the fact that they “both fell victim to the same criminals – mostly German, but also Soviet, communist”.

This year, the education minister launched a new state-funded research centre that aims to “counteract Christianophobia”, “disseminate knowledge about the persecution of Christians”, and “promote the Polish tradition of religious tolerance as a unique historical experience on an international scale”.

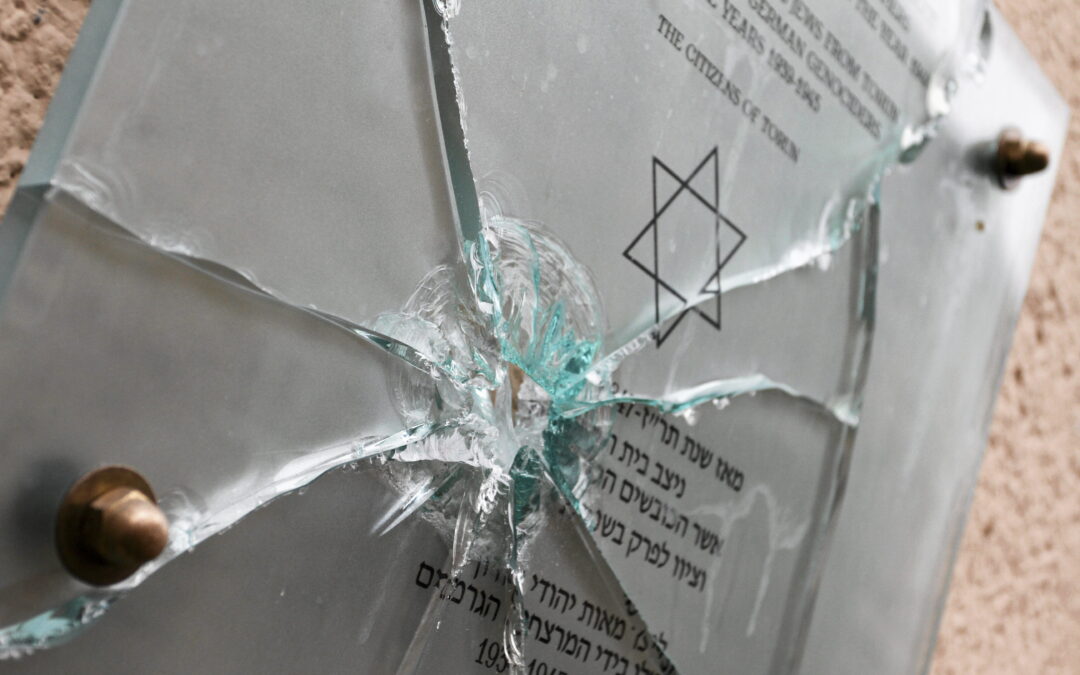

Main image credit: Mikolaj Kuras / Agencja Gazeta

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.