By Szymon Pifczyk

Christmas is coming. In pre-corona times, shopping malls in the United States would fill with queues of excited children waiting to meet Santa Claus and get a present from him. In Britain, it is the same character, but with a different name, Father Christmas, who does the honours.

The Nordic countries have the Yule Gnome, while in Austria, it is the new-born Christmas child who delivers the gifts. But ask a Polish person who brings the presents in their household, and their answer will depend on where in Poland they grew up.

On the Facebook page that I run, Kartografia Ekstremalna (“Extreme Cartography”), I have published a multitude of maps, on different topics and about different places across the world. But, every year, the most popular one by far is always my set of maps showing various Christmas traditions in Poland (it has also been shared wildly on the internet, often without acknowledging the source, unfortunately).

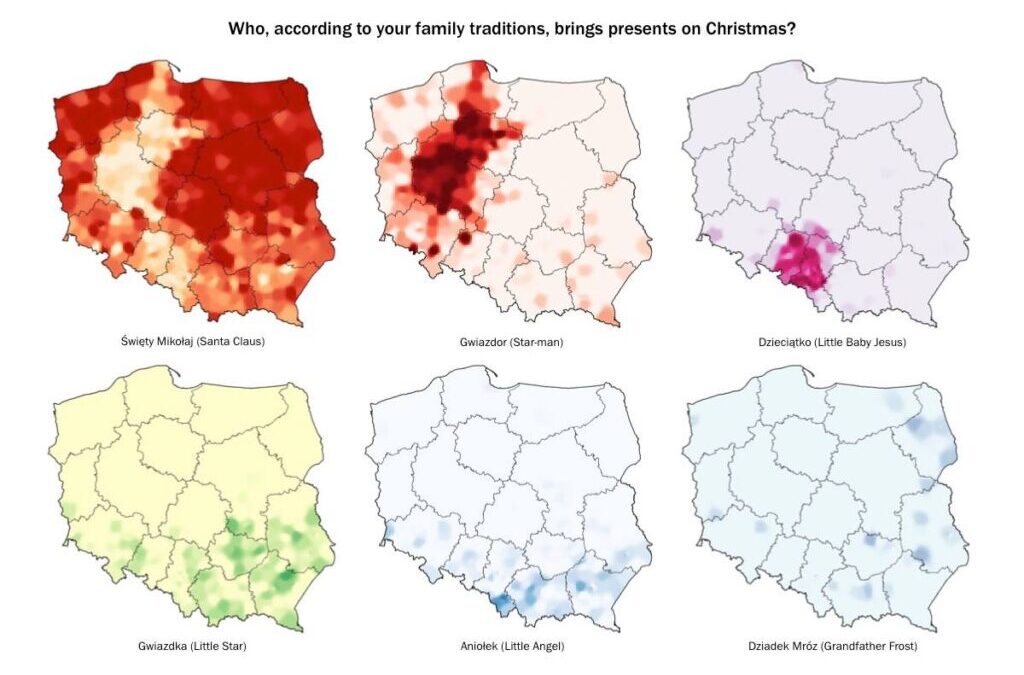

Originally published in 2015, it shows the result of a Christmas traditions questionnaire I created, which was completed by 4,500 people. One of the questions was: who, according to your family traditions, brings presents on Christmas? I also asked people to mark which of Poland’s 314 counties they lived in (or where their family was from, if they moved between regions).

The result was the set of maps that can be seen below.

The idea for this map came from my own experiences as a child. I grew up in Upper Silesia, a part of Poland that is always a little different. Upper Silesian culture is strong enough that, in the last national census, over 847,000 people declared Silesian nationality (which is not officially recognised by Poland), and over half a million said they speak Silesian at home (not officially recognised either).

In the 1990s and early 2000s, when globalisation came to Poland, Upper Silesian parents suddenly had to answer their children’s questions about why the Coca Cola commercial was saying that Święty Mikołaj (Saint Nicholas, or Santa Claus) brought presents on Christmas Eve. They had always been taught that he brings gifts on 6 December (Saint Nicholas Day), and it is the Little Baby Jesus (Dzieciątko) who comes at Christmas.

I vividly remember the anti-Santa campaign launched by local activists and the Catholic church (which had an additional incentive: Coca Cola’s Saint Nicholas was clearly not the the esteemed bishop of Myra).

To jeszcze był czas, gdy nie było amerykańskiego, otyłego krasnala. Był Święty Mikołaj! pic.twitter.com/lrK1w2rnkS

— Piotr Zarzeczański (@redaktorbs) December 18, 2020

Saint Nicholas continues to bring presents on 6 December, in a tradition that is observed by families and in schools throughout Poland. And across most of the country, Santa is also the most popular purveyor of presents at Christmas too in most parts of the country. That includes Warsaw, where most major media outlets are based, meaning he gets almost all the airtime around Christmas.

The character is still often portrayed in his more traditional garb as a Catholic saint. But this has increasingly morphed into the standard western, Coca-Cola-influenced representation of the jolly old white-bearded man in a red suit.

Yet in some parts of the countries, other traditions endure. While as an Upper Silesian kid I was told to wait for the Little Baby Jesus, children in Poznań were waiting for the “Star-man” (Gwiazdor), and some in Kraków were looking out for the Little Angel (Aniołek).

The roots of these differences – as is so often the case with Poland – lie in the country’s complicated history, and particularly the 123 years between 1795 and 1918 when it was wiped out from the map and partitioned between three neigbouring empires.

For example, the Gwiazdor of the Greater Poland Province is essentially the same as the German Weihnachtsmann – which is rather interesting, given that this figure comes from Protestant culture, rather than Poland’s now-dominant Catholic faith culture. But it also makes sense – the Star-man’s territory includes parts of Poland that belonged to Prussia before 1918.

That still leaves Upper Silesia, though. This region was also part of Prussia – in fact for even longer than Greater Poland. The tradition of the Little Baby Jesus giving presents might have arrived here from Austria via Moravia, and specifically through the Catholic clergy, as parts of Upper Silesia belonged to the diocese of Olomouc (a city in Moravia in the Czech Republic) as late as 1972.

Dzieciątko-like figures are present all over the former Austrian Empire (except for the Balkans). And this is not the only evidence of Austrian Catholic influence in Upper Silesia: the sublime hymn Te Deum is different in this region than elsewhere Poland, with a local version of the lyrics and melody taken from the Großer Gott, wir loben dich written in 1776 in Vienna (which English-speaking audiences might know as Holy God, We Praise Thy Name).

But if Dzieciątko was imported to Upper Silesia from the Habsburg Empire, then why do people in the part of Upper Silesia that remained under Austrian rule (the area around Cieszyn and Bielsko Biała) get their presents from the Little Angel (Aniołek) instead? I struggle to find a good answer. This part of the country is traditionally Lutheran, meaning that saints are not venerated, so it makes sense that Saint Nicholas is not particularly popular there. But why does Jesus not bring the presents to celebrate his birthday?

Reuters looks at Kraków's annual Christmas tradition of displaying "szopki", homemade (but often very elaborate) models of nativity scenes pic.twitter.com/uxx2h3QFTO

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 7, 2019

Could it be the contrarian nature of this part of the country? A traditional Lutheran stronghold in opposition to the Catholic Habsburgs, it seems plausible that they wanted to differentiate themselves in the category of Christmas gift-bringers as well. Or perhaps the custom predates that of the Little Baby Jesus?

A look at the broader map of Europe suggests this could be the case. Transylvania Hungarians and Hungarians in Slovakia also wait for an Angel, rather than the Christmas Child, and they settled away from their countries prior to the advance of the Austrian Empire.

Whatever the history, the Little Angel also spreads into Lesser Poland (Małopolska) Province – although it has a competitor there, in the form of the Little Star (Gwiazdka). This is a particularly interesting term, as it is has become synonymous in standard language and culture with Christmas time. Polish people throughout the country ask their friends “co robiłeś na gwiazdkę?” (“what did you do for Christmas?”).

The character of the Little Star seems to be originally Polish – in old folk tradition, it was a girl dressed in white among the group of traditional Christmas carollers – and it has also remained unique to Poland.

On the map, both the Little Star and the Little Angel make some territorial expansion into the west, particularly Lower Silesia. This is because of the population movements following the end of World War II. Thousands of people from poor and overpopulated Lesser Poland moved west following the expulsion of Germans from the region, bringing their own traditions. And while in most places in the so-called Reclaimed Territories the population blended with the “standard” Polish, it seems that in some places the share of Lesser Poland settlers was substantial enough to allow for their traditions to persevere.

Yet another bringer of Christmas gifts lingers in the east of Poland, although he is perhaps the least popular. Grandfather Frost, or Old Man Frost (Dziadek Mróz in Polish) is figure common to all Slavic and Orthodox countries. In Russia and Eastern Ukraine, communist rule eradicated traditional celebrations for Christmas and he instead comes on New Year’s Eve. In Poland, it is almost only the Orthodox minority that continues to celebrate him.

The diversity of Christmas traditions in Poland is rather surprising when one considers that, according to the last census, over 97% of people are ethnically Polish, and almost 96% of those declaring their religion are Catholic.

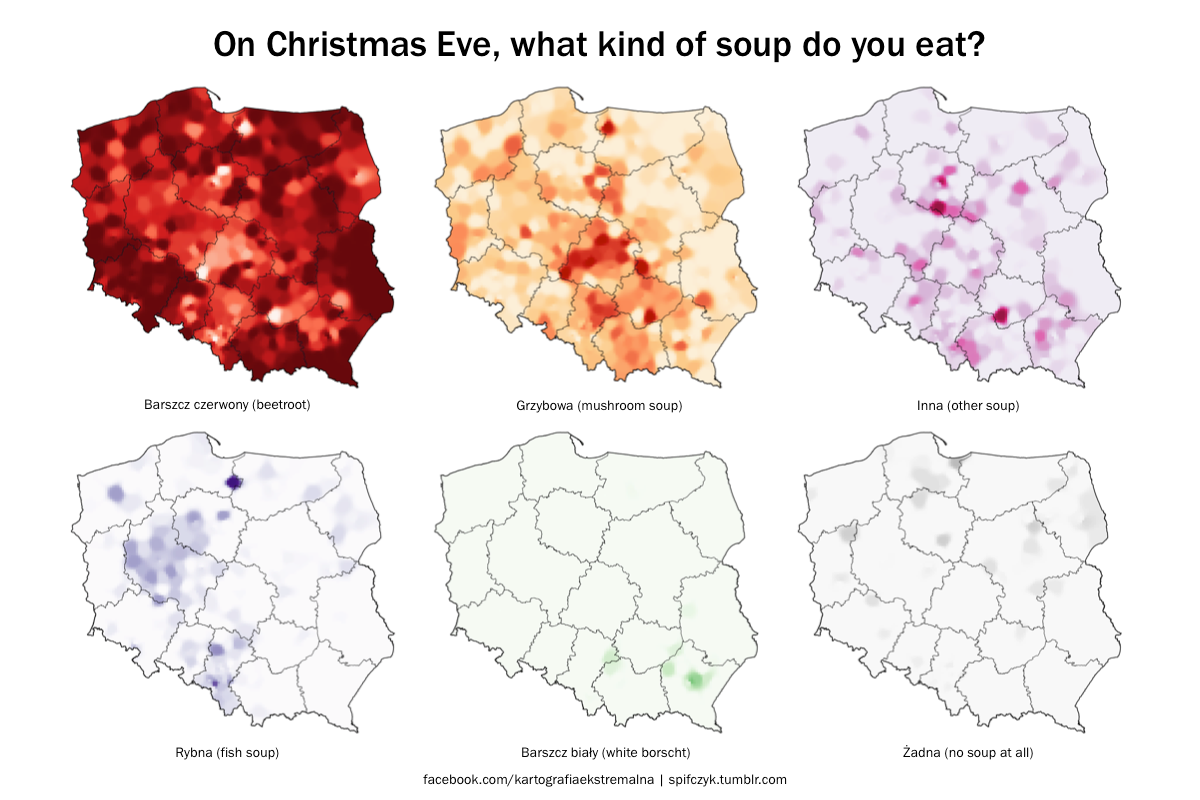

It also shows that Poland’s complicated history and location at the crossroads of Europe make an interesting mix that also extends to various other regional disparities. What people call house shoes, for example. Or, sticking to the theme of presents but on the occasion of another festivity, whether kids receive them for Easter or not. Or lastly, to return to Christmas, the types of soup served at the traditional Christmas .

Images belong to the author