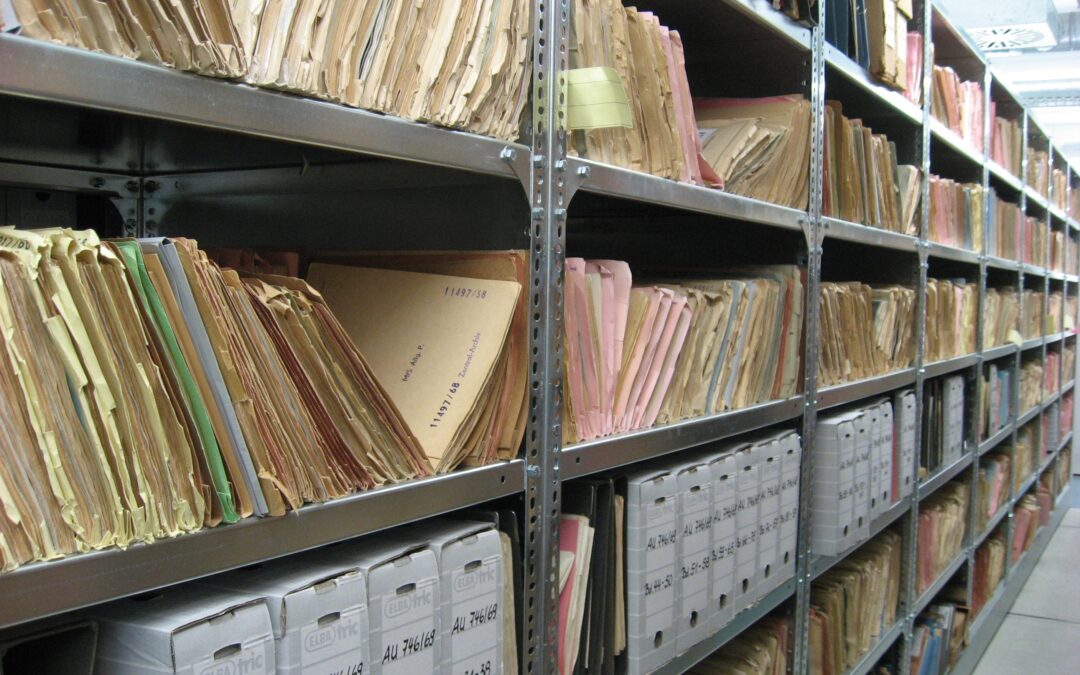

Over 100 documents from Poland’s communist-era security services that disappeared after the fall of the Iron Curtain have been discovered hidden in the possession of a former intelligence officer.

The files – which include some concerning agents of the Polish state operating abroad and others relating to the period of martial law in 1980s Poland – may contain important information, say prosecutors.

It is unlikely that an officer would have gone to such lengths to steal and hide documents that hold no value, notes Andrzej Pozorski, head of the commission for prosecuting crimes against the Polish nation at the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN).

The IPN – a state body charged with documenting and prosecuting communist crimes – led the operation to recover the documents in cooperation with the Internal Security Agency (ABW), Poland’s domestic counter-intelligence body.

They found the files – which were produced in the years 1979-90 and some of which are marked “top secret” – from apartments belonging to the former officer and some of his close contacts, reports the Polish Press Agency (PAP).

The officer, who worked for the intelligence services both before and after the fall of communism, now faces up to eight years in prison if found guilty of possessing the documents, which by law should be transferred to the IPN.

“The case confirms that, at the turn of the 1990s, when the communist system in Poland was collapsing, officers of the Security Service (SB) took documents and have illegally kept them until today,” says Pozorski.

This was often done, suggests Pozorski, by those who wanted to help their careers after the transition to democracy.

The documents will potentially be of value both in prosecutions – with the government having recently removed the status of limitations on communist-era crimes – as well as for historians, adds Pozorski.

Many documents from the communist-era disappeared after 1989, notes PAP. Some were destroyed, while others ended up being kept in private hands.

In 2016, following the death of Czesław Kiszczak, who led the interior ministry from 1981-90, the IPN seized hundreds of pages of documents from his home after his widow tried to sell them.

Some of the files appeared to confirm earlier claims that Lech Wałęsa, leader of the Solidarity movement that helped bring down the communist regime, had previously been a paid informant of the security services.

Following handwriting analysis, the IPN declared that Wałęsa’s signature in the documents is genuine. But Wałęsa himself maintains that they are a forgery designed to discredit him.

Many in Poland – including the currently ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party – have argued that not enough was done to purge former communists and their allies from positions of power after 1989.

They claim that, instead, a “post-communist” system developed as part of an agreement between parts of the former regime and some of its opponents, allowing them to retain control over politics, business, the judiciary and the media.

“We are still today cleansing Poland of all kinds of dirt that was introduced by that era,” said President Andrzej Duda, a PiS ally, earlier this year. “There are still elements from the former era that must be removed, replacing them with new tissue.”

Opponents, however, note that the government leading this “decommunisation” policy has itself appointed former communist-era officials to senior positions. They argue that its rhetoric is simply a way for it to justify policies – such as the overhaul of courts – designed to assert its own control over institutions.

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.