Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Poland’s demographic decline accelerated further in 2025, as the country recorded around 168,000 more deaths than births. It was the 13th year in a row that more people have died than been born in the country.

Preliminary data from Statistics Poland (GUS), a state agency, show that Poland’s population fell by 157,000 in 2025, reaching 37.33 million. That represented an annual decline of 0.42%, more than the decline of 0.39% recorded the previous year.

In a statement accompanying the data, GUS struck a pessimistic note, saying there was little prospect of a reversal in Poland’s negative demographic trends given the country’s birthrate (which is one of the lowest in the world) and the emigration of young people.

“The low fertility rate, which has persisted for about three decades, will continue to contribute to low birth rates, especially in the context of the systematic decline in the number of women of reproductive age,” wrote the agency. “This trend is further exacerbated by the persistently high level of emigration abroad.”

Poland’s population has fallen almost every year since 2012, when it stood at 38.53 million. The one exception was 2017, when there was a small rise (of less than 1,000).

Those figures have been driven by the fact that the number of deaths in Poland has been higher than the number of births every year since 2013.

And 2025 was no exception: 238,000 babies were born (14,000 fewer than a year earlier) while 406,000 deaths were recorded (3,000 fewer than in 2024).

This means the gap between deaths and births reached 168,000, up by over 11,000 from the previous year and the highest since the pandemic year of 2021, when deaths rose to record levels.

GUS notes that these demographic trends are changing not just the size but also the shape of Poland’s population.

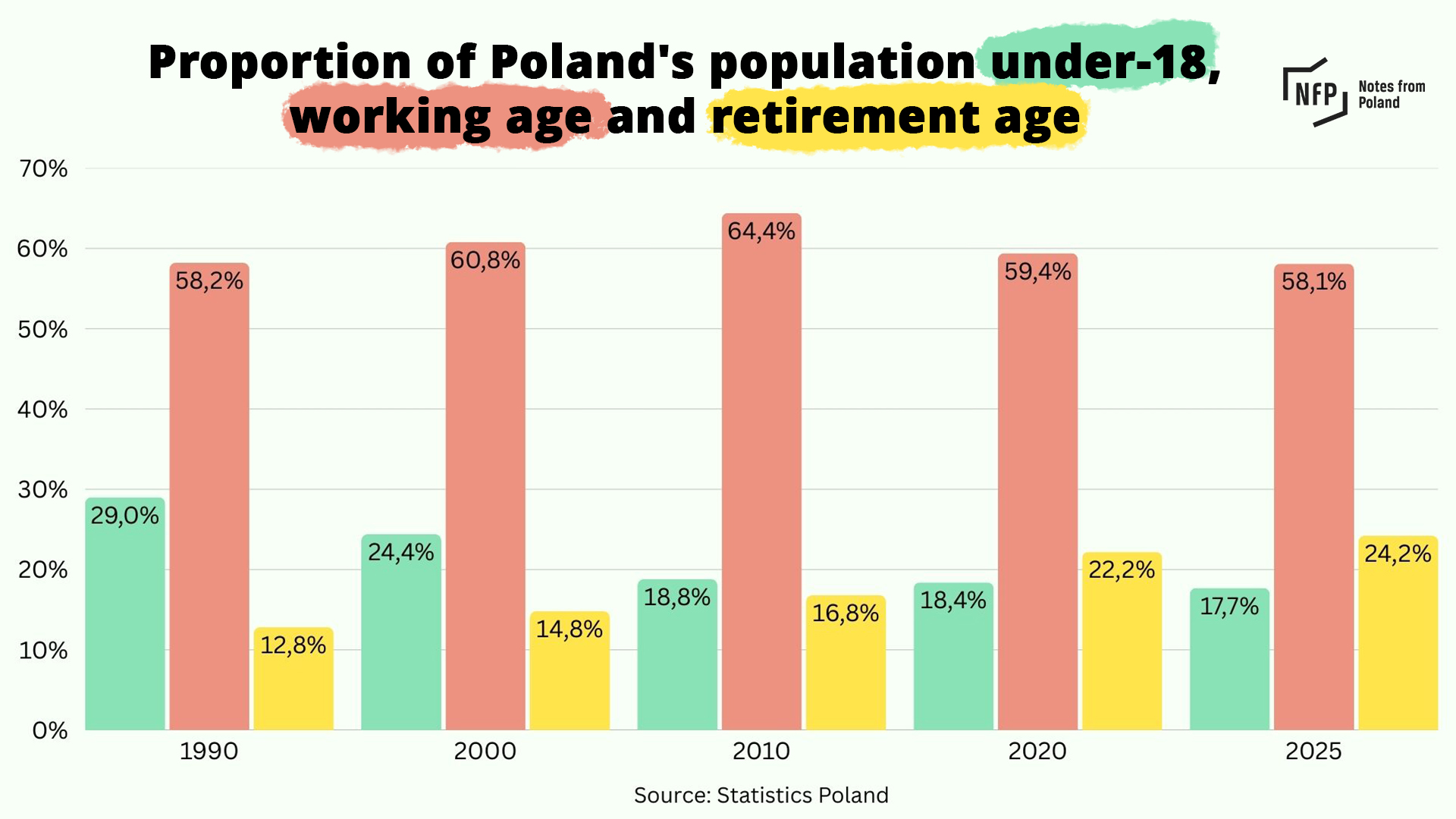

In 2025, 24.2% of the population was above retirement age (defined as over 60 for women and 65 for men) up from 22.2% in 2020, 16.8% in 2010, and 12.8% in 1990.

Meanwhile, people of working age made up 58.1% of the population last year, down from 59.4% in 2020 and 64.4% in 2010.

The share of children has fallen sharply. People aged under 18 accounted for 17.7% of the population in 2025, compared with 18.4% in 2020, 18.8% in 2010, and 29% in 1990.

Together, these trends mean that Poland’s dependency ratio – the number of people not of working age for every 100 working-age people – stood at 72 in 2025. That is the same level as in 1990, but the makeup of that figure has changed significantly.

In 2025, for every 100 working-age people, there were 30 people aged under 18 and 42 people of retirement age. In 1990, those figures were very different: 50 were below working age, and just 22 were above it.

The shift means that today’s workforce is supporting more retirees and fewer children than three decades ago, adding pressure to pensions, healthcare and the labour market.

However, figures released last year by GUS showed that the number of workers in Poland has actually reached its highest ever level, thanks to more people remaining in work beyond retirement age and previously economically inactive adults, especially women, entering the labour market.

Despite a shrinking and ageing population, the number of workers in Poland has reached its highest ever level, as more people remain in employment beyond retirement age and previously economically inactive adults, especially women, enter the labour market https://t.co/OvYCalIPK8

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 2, 2025

According to GUS’s experimental calculations published in November, which accounted for lower birth rates, Poland’s population could fall to just 29.4 million by 2060, 1.5 million lower than the official forecast published in 2023.

Poland’s worsening demographic situation has been at the centre of public debate for years, with various governments trying to address the issue. However, a range of state incentives – from raising child benefit to renewed funding for IVF – have failed to halt the demographic slide.

Analysts say that economic insecurity, limited access to affordable housing, and a restrictive abortion law have all contributed to the reluctance of young Poles to have children.

Immigration has partly softened the impact of population decline, with Poland recording some of the highest migration inflows in the European Union. But the state Social Insurance Institution (ZUS) cautions that it is “unrealistic” to assume migration will be high enough to counter demographic decline.

Poland’s population could shrink even more than previously forecast, according to a new simulation by the state statistics agency that assumes current record-low birth rates will continue.

The population would fall to 29.4m by 2060, down from 37.4m now https://t.co/ewhEYpj8gP

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) November 7, 2025

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Olesia Bahrii/Unsplash

Alicja Ptak is deputy editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland and a multimedia journalist. She has written for Clean Energy Wire and The Times, and she hosts her own podcast, The Warsaw Wire, on Poland’s economy and energy sector. She previously worked for Reuters.