Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Daniel Tilles

On Thursday, 18 December, President Karol Nawrocki vetoed three government bills. In doing so, he passed a symbolic milestone.

It meant that, four and a half months since taking office, Nawrocki has vetoed 20 bills passed by parliament, overtaking the 19 vetoes issued by his predecessor, Andrzej Duda, during his entire ten-year term.

At Nawrocki’s current rate of one veto every 6.7 days on average, he will surpass Poland’s presidential veto record holder – Aleksander Kwaśniewski, who used his power 35 times in ten years – by the end of March 2026.

Meanwhile, Nawroocki has also submitted an unprecedented number of bills of his own to parliament – 14 so far – on a range of issues, from energy prices and healthcare funding to animal rights and benefits for Ukrainian refugees.

In many cases, Nawrocki has combined the two powers: vetoing a government bill while then proposing what he says is a better alternative of his own.

President Nawrocki has vetoed two government bills raising taxes on alcoholic and sweet drinks, as well as on winnings from competitions and gambling.

Nawrocki accused the government of trying to take the "easy route" of "reaching into Poles' pockets" https://t.co/k0CJon8yQN

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 19, 2025

All of this shows how Nawrocki is seeking to redefine Poland’s presidency, a position that has previously been seen as largely a symbolic, figurehead role.

He is pushing every limit of presidential power in an effort to create something closer to a semi-presidential system in which responsibility for governance is shared between the prime minister and president.

In doing so, Nawrocki also wants to establish himself as the leader of the right-wing opposition in Poland, standing up to Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s government in a way that the national-conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party, which supported Nawrocki’s candidacy, cannot do with its parliamentary minority.

Is it working? So far, yes, to a great extent – though big questions remain over what Nawrocki’s end goal is and whether these tactics will get him there.

Initially, many polls indicated that the public were impressed with this new, more assertive president. In mid-September, a United Surveys poll for Wirtualna Polska found that 57.5% of respondents viewed Nawrocki’s presidency positively, and only 32.9% negatively.

In late November, regular polling on trust in politicians by the IBRiS agency for Onet found that Nawrocki had stormed to the top of the ranking, with trust of 51.8%, the third-highest figure ever recorded for any politician.

Last week, an SW Research poll for Rzeczpospolita asked who Poles regard as the leader of the right in their country. Nawrocki came top, with 28.9%, ahead of PiS chairman Jarosław Kaczyński (19%), who has for the last two decades been the leading figure on the Polish right.

🔴 TYLKO U NAS: #Sondaż: Polacy wskazali lidera polskiej prawicy. @OficjalnyJK przegrywa z @NawrockiKn

Kliknij w zdjęcie, by poznać wyniki sondażu 🔽 https://t.co/zzzgLAsQrN

— Rzeczpospolita (@rzeczpospolita) December 20, 2025

However, polls also point to three clear dangers for Nawrocki.

First, that the public may begin to tire of his constant obstructionism. Earlier this month, another SW Research poll for Rzeczpospolita found that 44.1% believe that Nawrocki is “abusing his veto power” while 39.6% said that he was “using it appropriately”.

Nawrocki in particular appears to have lost the narrative battle over two recent vetoes – of a bill banning the chaining up of dogs and another introducing regulation of the crypto-asset market.

Two polls this month have found that a majority of the public disapprove of the dog-chaining veto. The government has accused Nawrocki of threatening national security with the crypto veto.

Thousands of people have protested in Warsaw against President @NawrockiKn's veto of a law that would have banned the chaining up of dogs

Parliament will vote on Wednesday on whether to overturn Nawrocki's veto, which would require a three-fifths majority https://t.co/0GRup2sppb

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 15, 2025

Second, Nawrocki’s confrontation with the government appears to be bolstering Tusk, an experienced and canny political operator who relishes nothing more than a one-on-one battle – previously so often with Kaczyński, and now with Nawrocki.

After Nawrocki defeated Tusk’s presidential candidate, Rafał Trzaskowski, there were questions over whether the prime minister might be pushed out of office. But Tusk appears reenergised, and has put to bed any questions over his leadership.

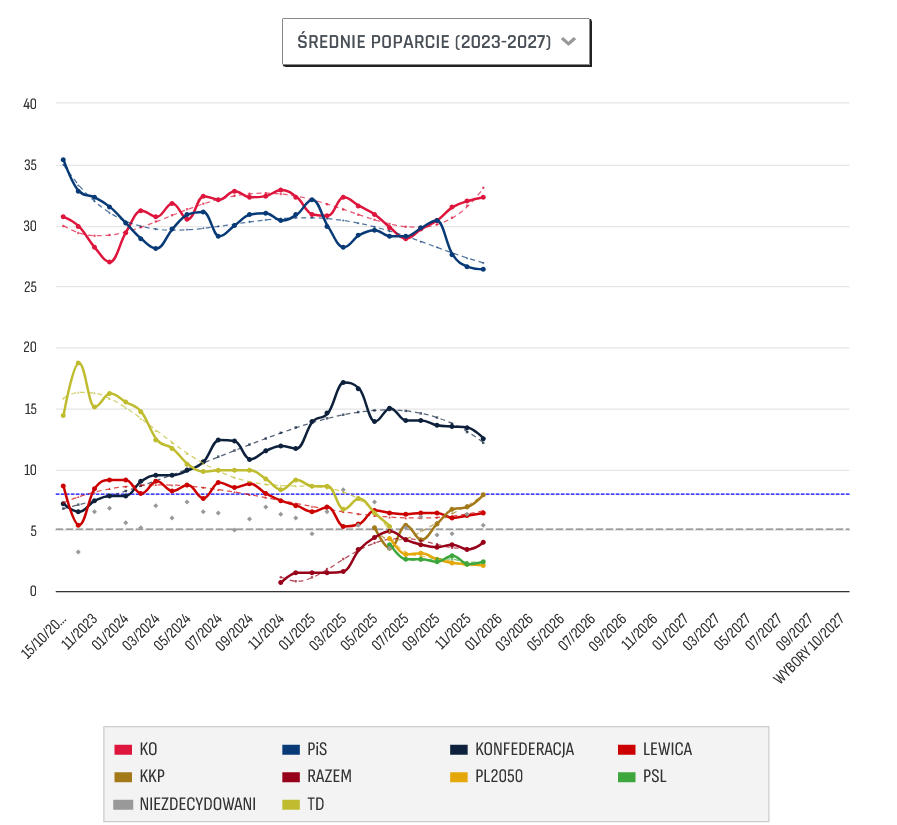

Since August, the average poll rating of his centrist Civic Coalition (KO) party has risen from just below 30% to over 32%, according to the E-wybory aggregator. Meanwhile, PiS, which might have hoped for a boost from Nawrocki’s victory, has fallen from 30% to around 26% over the same period.

Monthly polling averages compiled by E-wybory.

And this points to the third question – and potential danger – for Nawrocki. His success appears to have come at the expense of PiS. Whereas Duda was clearly PiS’s man – often mockingly described as “Kaczyński’s pen” – Nawrocki, who had never stood for office before this year, is not tied to any party.

He officially stood for the presidency as an independent, albeit with PiS support, and during his campaign flirted with the far right and took positions that contradicted PiS’s – for example, his tough line on Ukraine, including opposition to its NATO and EU membership.

As I wrote after Nawrocki’s remarkable election victory, his presidency presents major challenges for PiS. And, so far, the party has struggled to deal with them. It is currently mired in infighting, some of which has broken out into public mudslinging, with senior party figures criticising one another.

🎥‼️ "Nie" dla @MorawieckiM jako premiera w najbliższej perspektywie. @SasinJacek: To nie jest to, czego oczekują wyborcy prawicy. PiS powinno podążać w stronę konserwatywną‼️@RadioZET_NEWS #GośćRadiaZET @BogRymanowski

Cała rozmowa ⬇️https://t.co/o780wG4gQz pic.twitter.com/hjqttuDNEO

— Gość Radia ZET (@Gosc_RadiaZET) December 8, 2025

One cause of this is the fact that Nawrocki has effectively made himself a one-man opposition, sucking attention away from PiS.

Meanwhile, his hard-right position on many issues has exacerbated tensions between more moderate and hardline factions in PiS. There have even been recent rumours of Mateusz Morawiecki, a relative moderate who served as prime minister from 2017 to 2023, leaving PiS entirely and seeking to create his own centre-right formation.

Even if such talk is exaggerated, the right-wing opposition is looking increasingly fragmented. As PiS’s support has declined, the radical-right Confederation of the Polish Crown (KPP) of Grzegorz Braun has risen to around 7% support, while the far-right Confederation (Konfederacja) is on around 12%.

Nawrocki openly courted Confederation leaders and voters during his presidential campaign and also responded positively to some of Braun’s demands, eventually earning the radical-right leader’s endorsement in the second-round run-off.

A new poll shows the party of far-right leader Grzegorz Braun reaching third place for the first time, with support of 11%

The finding continues a dramatic recent rise for Braun, who is currently on trial for attacking a Hanukkah celebration in parliament https://t.co/XeKwJy6YLG

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 17, 2025

If Nawrocki’s aim is to make himself the new figurehead of the Polish right, he is so far succeeding. However, if he also wants to remove Tusk’s government at the 2027 parliamentary elections and bring to power a new one with which he is more closely aligned, there are clear dangers to his current approach.

His obstructionism may continue to bolster Tusk, whose KO could emerge even stronger in the 2027 election (remember that it actually finished second to PiS in 2023, but was able to take power as part of a broad coalition that has since been difficult to manage).

That would give Tusk the first shot at forming the next government. But, even if he is unable to do so, any PiS-led coalition government that emerges may be unstable given the current fragmentation on the right.

PiS differs significantly from Confederation and KPP on many issues and they would not make comfortable bedfellows. When, in 2005-2007, PiS ruled with two smaller, radical populist parties, Self-Defence (Samoobrona) and League of Polish Families (LPR), it was a recipe for instability, eventually leading to early elections that saw Tusk come to power.

In the early months of his presidency, Nawrocki has successfully positioned himself as an alternative centre of power to Tusk’s government. However, at some stage, he may be forced to decide whether to forgo some of the benefits that brings to his personal political brand and instead focus on the broader goal of helping a stable and effective right-wing government win power in 2027.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Łukasz Błasikiewicz/KPRP

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.