Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Daniel Tilles

OPINION

Karol Nawrocki’s triumph is a huge blow to Donald Tusk’s ruling coalition, but also presents challenges – and opportunities – for the conservative opposition.

Karol Nawrocki’s victory in Poland’s presidential election, while not necessarily unexpected given close polling in the final stages of the race, represents a remarkable achievement.

When he announced his candidacy in November, Nawrocki, the head of a state historical body, had never stood for any form of elected office. One poll at the time showed that almost half of the public, 46%, did not even know who he was.

He was up against Rafał Trzaskowski, a seasoned politician, former government minister and current mayor of Warsaw, who had effectively been preparing his presidential bid for five years, since losing the 2020 election.

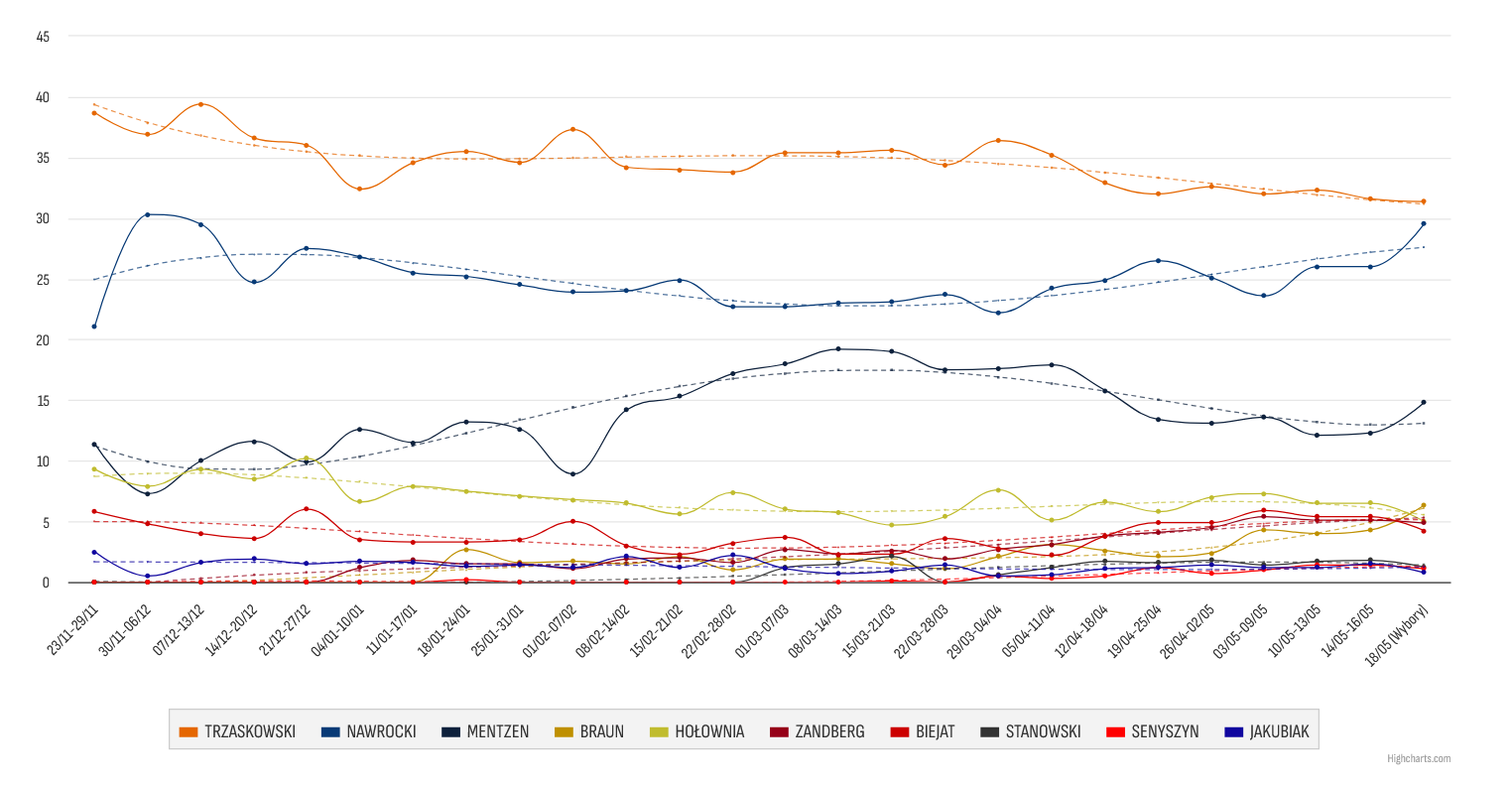

Ahead of the first round of this year’s election, Trzaskowski led in the polls throughout the entire campaign, often by over 10 percentage points.

Weekly polling averages ahead of the presidential election first round, compiled by eWybory.eu.

But Nawrocki diligently and effectively worked to close that gap, campaigning energetically around the country and taking advantage of his rival’s slip-ups. According to MamPrawoWiedzieć, an NGO that monitors politicians’ activity, Nawrocki held 262 campaign events before the election first round compared to Trzaskowski’s 146.

Although technically an independent, Nawrocki also had the support of Law and Justice (PiS), Poland’s main opposition party, which retains a large and committed electorate.

When Nawrocki was hit by major scandals in the final stages of the campaign – in particular over revelations regarding a second apartment he owned – he defied the commentators (including myself) who suggested that they could kill off his presidential ambitions.

Even allegations published days before the final vote that Nawrocki had helped procure prostitutes for clients of a luxury hotel where he once worked (vigorously denied by the candidate) were not enough to dent his support.

Conservative presidential candidate @NawrockiKn says he will sue news website @onetpl for claims it published today that he procured prostitutes for clients at a luxury hotel when working there as a security guard.

He called the report "a bunch of lies" https://t.co/WZ4rZWfFT1

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 26, 2025

There are a variety of likely factors behind Nawrocki’s victory. A primary one is that Poland remains a deeply conservative country. Moreover, these elections took place in the context of a turbulent and dangerous international situation, making Nawrocki’s tough-guy image more appealing.

But probably above all, the result reflects the unpopularity of Donald Tusk’s government, which since coming to power in December 2023 has achieved little of its promised agenda, disappointing its supporters while also angering conservatives with many of its actions.

Trzaskowski, as deputy leader of Tusk’s Civic Platform (PO), had the difficult role of running as a representative of the ruling coalition. He made only half-hearted and unconvincing efforts to present himself as independent of it.

Nawrocki, meanwhile, had the much easier task of harnessing anger and frustration towards the government, as well as the preference among many voters that it would be better not to have the unpopular ruling establishment hold complete power.

As Donald Trump has shown, such anger can be powerful enough to override whatever personal deficiencies might seem to tarnish the candidate himself.

Moreover, as Nawrocki has never been a member of PiS (or any political party), he could effectively distance himself from unpopular aspects of its time in government and appeal to voters tired of the PO-PiS duopoly that has dominated Polish politics for two decades.

Conservative presidential candidate @NawrockiKn has signed a list of eight demands presented by his eliminated far-right rival @SlawomirMentzen.

Among the pledges are not agreeing to Ukraine's entry to NATO or any expansion of the EU's competences. https://t.co/bJ0u7uElCV

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 22, 2025

Nawrocki’s victory will present a major – and seemingly insurmountable – obstacle for the ruling coalition government, which had been desperately hoping for a Trzaskowski victory. It also presents challenges – but also major opportunities – for PiS.

Prime Minister Donald Tusk will now find it impossible to advance most of his agenda, given the president’s power to veto bills or send them to the PiS-aligned constitutional court for review (which at the moment is effectively a veto).

Any hopes of judicial reform, introducing same-sex civil partnerships or softening the abortion law (the latter of which may not have been possible even with a Trzaskowski presidency) are now effectively extinguished.

Meanwhile, it now looks extremely difficult for the ruling coalition to win a second term at the 2027 parliamentary elections, given that Nawrocki will be in office until 2030 and re-electing a government led by Tusk or one of his allies would simply result in more years of political gridlock.

"I currently do not envision Ukraine in either the EU or NATO," says the presidential candidate of Poland's conservative opposition PiS party.

He also pledged to veto bills ending the near-total abortion ban or introducing same-sex civil partnerships https://t.co/GNcXnAx5r0

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) January 9, 2025

Relations with Ukraine are also likely to become more tense, given Nawrocki’s pledge not to support its accession to NATO, his tough line on dealing with the legacy of World War Two massacres of ethnic Poles by Ukrainian nationalists, and his demands for a law giving Poles priority access to public services ahead of immigrants (most of whom are Ukrainians).

Nawrocki’s hardline stance on Ukraine also points to the questions his victory raises for PiS, given that many of the positions he has taken during the campaign have directly contrasted to those presented by PiS when it was previously in power.

PiS, for example, was a strong supporter of Ukraine’s NATO membership. Nawrocki has also openly criticised decisions by the former PiS government to allow the passage of the EU’s flagship Green Deal, to admit significant numbers of immigrants to Poland from majority-Muslim countries, and to introduce a major tax overhaul.

He has also pledged to end the practice – started by former PiS President Lech Kaczyński and followed by the current PiS-aligned incumbent Andrzej Duda – of inviting Jewish leaders to light Hannukah candles in the presidential palace.

The presidential candidate of Poland’s conservative opposition PiS party says he would end the tradition of lighting Hanukkah candles with Jewish leaders in the presidential palace.

The practice began in 2006 under Lech Kaczyński and has continued since https://t.co/xJb42sWePx

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) January 13, 2025

All of this shows that Nawrocki represents a harder-right position than PiS has in the past. Certainly, some of his declarations were made with the aim of attracting the far-right votes that Nawrocki needed to win the presidential run-off. But they also seem to be genuinely held.

The question for PiS now will be how it adapts to those positions, and what the effect will be if it shifts further to the right. Recent months have already seen it move in a more Trump-like direction, as it enthusiastically welcomed his return to the White House.

Trump’s homeland security secretary, Kristi Noem, endorsed Nawrocki days before the final round of the election, while Trump himself recently met with Nawrocki at the White House.

Donald Trump’s homeland security secretary, Kristi Noem, has called on Poles to elect conservative Karol Nawrocki as president during a speech today at CPAC Poland, days ahead of his election run-off against government-aligned centrist Rafał Trzaskowski https://t.co/eMP13DEwgv

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 27, 2025

PiS also faces a growing challenge from the far-right Confederation (Konfederacja) party, whose candidate, Sławomir Mentzen, finished a strong third in the election first round, with a former Confederation leader, Grzegorz Braun, coming fourth.

However, Nawrocki’s victory represents a personal triumph for PiS’s longstanding leader Jarosław Kaczyński, who has once again shown his political nous in picking a relative unknown who has now stormed to the presidency – just as he did in 2015 with Andrzej Duda.

And just as Duda’s victory helped pave the way for PiS, then in opposition, to return to power at the next parliamentary elections, Kaczyński will be hoping for a similar effect this time around.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Robert Kowalewski / Agencja Wyborcza.pl

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.