Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Olivier Sorgho

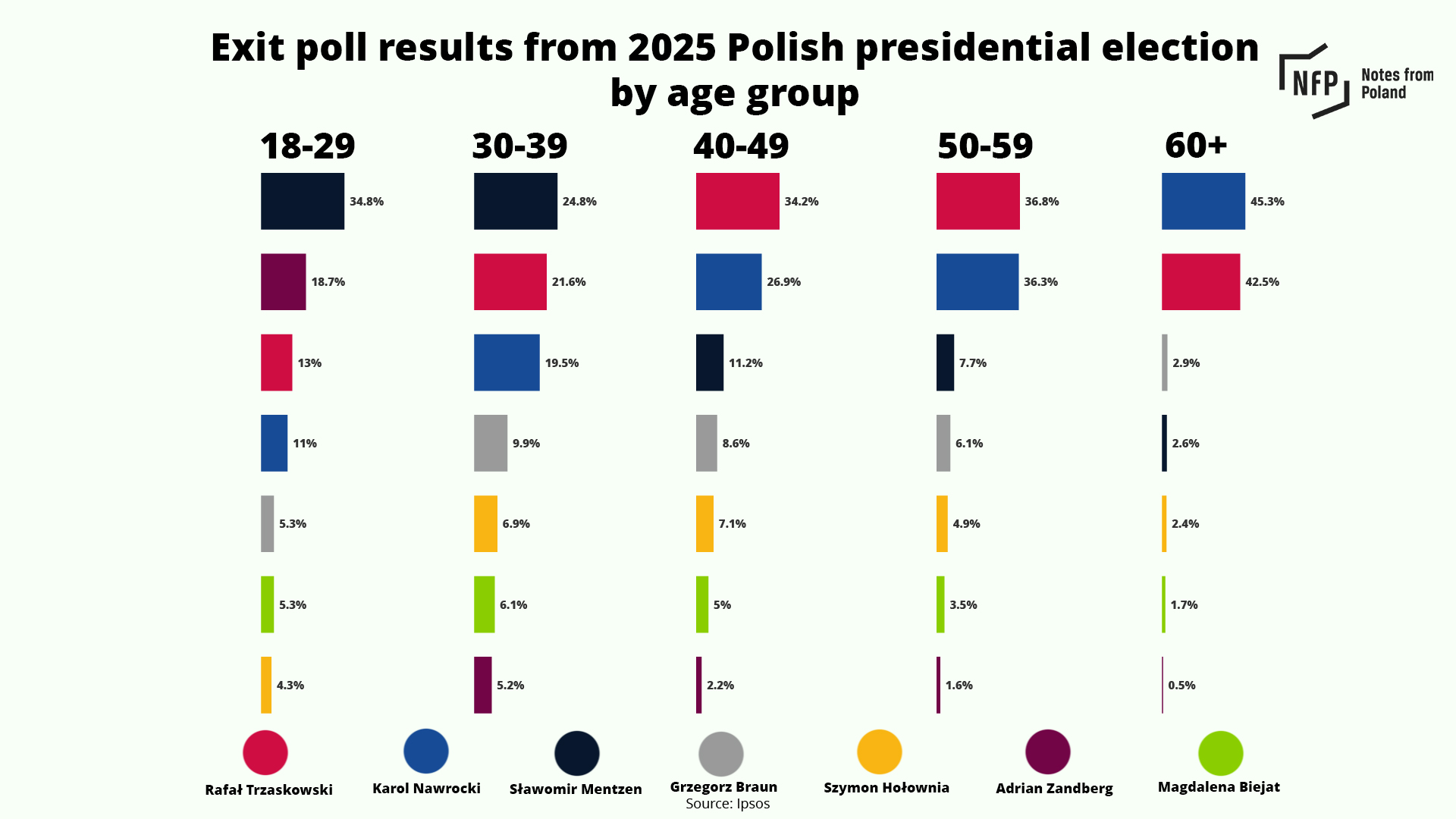

The first round of Poland’s presidential election was won by candidates representing the two parties that have dominated Polish politics for the last 20 years: Rafał Trzaskowski of the centrist Civic Platform (PO), Poland’s main ruling party, came first while Karol Nawrocki, supported by the national-conservative opposition Law and Justice (PiS) party, was second.

But the result was very different among the youngest voters, who mainly backed two candidates from anti-establishment parties on opposite ends of the political spectrum.

According to the exit poll, among voters aged 18 to 29, Sławomir Mentzen of the far-right Confederation (Konfederacja) party came first, with 34.8% of the vote, while Adrian Zandberg of the left-wing Together (Razem) party was second, with 18.7%.

Perhaps surprisingly, some of the young voters Notes from Poland spoke to were drawn to both candidates, despite their stark differences on issues ranging from the economy to abortion, and attitudes towards the European Union.

“There are some voters who are just looking around for whoever is the best challenger to the duopoly, to the established political parties,” explains Aleks Szczerbiak, professor of politics at the University of Sussex. “And they are more likely to be among younger voters.”

The youth exodus from PO and PiS

Trzaskowski and Nawrocki advanced to the second-round run-off after securing a combined 60.9% of votes in the first round. But only 24% of voters aged 18 to 29 backed them, down from the 43.1% who in 2020 voted either for Trzaskowski or Andrzej Duda, the PiS-backed candidate who won that election.

“Our generation has had enough of PO-PiS, these parties should be forgotten, and if things continue as they are, this will eventually happen,” says Miłosz Sygut, a Zandberg voter from Wrocław.

Neither party has sufficiently dealt with the problems facing young people, including a lack of affordable housing and unstable employment, explains political scientist Marta Żerkowska-Balas from SWPS University.

Poland has recorded the highest annual rise in housing prices in the EU for the third quarter in a row.

Prices rose by 17.7% year-on-year in the second quarter of this year, compared to an EU average of 2.9% https://t.co/y2lfGQa9yY

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 7, 2024

Among young people, 81% believe that the government mostly serves the interests of older generations, according to a recent study by the NGOs More in Common and Ważne Sprawy.

“PiS and PO keep arguing over whether to give seniors a 14th or 15th [extra monthly] pension [instalment each year],” says Kostas Kundelis, a 29-year-old Mentzen voter from Wrocław. “For me, those parties are the same: completely unreliable, lacking any concrete views, but just vying for power,” he adds.

PiS’s conservatism on issues like abortion and LGBT+ rights has alienated young progressives while its welfare policies – which offer support in particular to families and the elderly – are unappealing to, and can even be seen as coming at the cost of, the young.

The PO-led ruling coalition, meanwhile, has so far failed to deliver on its 2023 election promises such as reversing PiS’s near-total abortion ban, raising the income tax threshold, and subsidising rent for young tenants.

Polls conducted to mark one year since @donaldtusk took power show that most Poles negatively assess the work of his government so far and many more feel their lives have got worse than better.

Women and young people are particularly disappointed https://t.co/QWZWvbyQbW

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 13, 2024

More than just protest votes

Mentzen’s and Zandberg’s opposition to the PiS-PO duopoly played an important role at the ballot box, a number of their voters told Notes from Poland. But the candidates also held clear positions that resonated with young people.

According to a report by the Batory Foundation, which cited data from More in Common, migration and the war in Ukraine are the leading sources of anxiety among young Poles, many of whom perceive migrants as competitors for jobs and public services.

Zandberg is open to asylum seekers but has criticised the influx of foreign workers under PiS and its impact on the job market. Mentzen accuses migrants of free-riding on Poland’s welfare system, and calls the EU migrant pact a threat to national security and culture.

Patryk Kotomski from the town of Namysłów was torn between Mentzen and Zandberg, but backed the former due to his criticism of the EU’s migration policy and Green Deal, as well as his opposition to sending Polish troops to Ukraine.

“I understand that migration can help with our ageing population. But I worry about uncontrolled migration by people who do not assimilate. Russia and Belarus are pushing such people into Poland to destabilise us,” he says, adding that he disagrees with Mentzen’s hardline views on abortion and tax-abolition proposals that could deprive the state of necessary funds.

The number of foreigners in Poland’s social insurance system rose 6% in 2023 to reach 1.13 million. Immigrants now make up almost 7% of all those in the system

The largest increases were recorded by Belarusians, Ukrainians, Indians, Colombians and Nepalis https://t.co/eA1QVo0ydH

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) January 27, 2024

The Batory Foundation report suggests that young people rank improving the quality of healthcare as the most important priority for the government, while lowering the cost of living ranked third.

Those are flagship topics for Zandberg, who advocates raising public healthcare spending to 8% of GDP, and calls for launching a state programme to build affordable housing.

“As an insider, I see how inefficient the public healthcare system is,” says Karolina Rosenberg, a 29-year-old doctor from Wrocław who voted for Zandberg.

“Many doctors work quarter-time in public healthcare to attract patients to their private businesses,” she continues, adding that she supports Zandberg’s proposal for doctors to have to choose between the private and public sector.

Young Poles’ frustrations with dysfunctional public services have left many feeling that they must rely on themselves or family, according to the Batory Foundation report. Its authors suggest that this is one of the reasons why Poland’s youth tends to support privatisation, deregulation and low taxes.

“Mentzen was more pro-entrepreneurial,” says Kotomski, explaining another reason why he backed the far-right candidate over Zandberg. “The prosperity we have in the country is partly thanks to entrepreneurs… [Running a firm] can be such a hassle, which could be relieved by simplifying taxes and bureaucracy.”

The freedom to express themselves, including on the internet, is also key to Mentzen’s electorate of mostly largely men from smaller towns, Szczerbiak explains. His voters care less about secularism, minority rights and abortion rights than supporters of Zandberg, who are largely progressives of both sexes living in big cities.

“Right-wing candidates were not an option for me, because they support the church, are against gay people and against abortion rights. Those are dealbreakers for me,” says Dawid Dziurzyński, a 26-year-old Zandberg voter from Wrocław.

Memes, online ads and slogans

For some young voters drawn to both Zandberg and Mentzen, ideological differences took a back seat, says Kamil Smogorzewski, communications director at pollster IBRiS.

“What mattered most was that they represent not only a completely different approach to doing politics and to the language of campaigning, but above all they also embody generational change thanks to their clear views,” he continues.

“Both Mentzen and Zandberg speak a language that young people understand and use social media, which is a natural means of communication for youth,” Żerkowska-Balas explains.

Another Batory Foundation study found that 97% of Mentzen’s political ads on Meta’s platforms, including Facebook and Instagram, predominantly reached people under the age of 34, compared to a figure of 56% for Zandberg.

Far-right candidate @SlawomirMentzen's rise in the polls has turned Poland's presidential election into a three-horse race

Mentzen has managed to detoxify his party and has benefited from other candidates mainstreaming its positions, writes @danieltilles1 https://t.co/Ql9LihJ7tu

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 28, 2025

Mentzen’s campaigning in small towns, where he organises beer-drinking sessions and takes selfies with supporters, has made him appear as a regular, accessible person, found pollster CBOS in a study of his supporters.

Meanwhile, Zandberg is seen by many voters, including some of Mentzen’s supporters, as a confident debater. A clip from a televised debate of him confronting Mentzen by replaying footage of his rival proposing to abolish annual monthly pensions went viral on the likes of TikTok.

“I enjoy listening to Zandberg, you cannot out-argue him. He is knowledgeable and has a presidential demeanour,” says Kundelis, who does not rule out voting for the Together leader in the future if Poland’s security and prosperity improve enough for him to be more open to the left.

The young generation often forms opinions about candidates based on memorable moments in the media and catchy slogans rather than their detailed political programmes, adds Smogorzewski. “Young voters, but not only them, are often unaware of what lies behind candidates’ slogans.”

Cracks in Poland’s political duopoly

Trzaskowski and Nawrocki’s combined result in the first round was the worst electoral performance of the PO-PiS duopoly since 2005, Smogorzewski points out. “This was not an election between PiS and PO or even the broadly understood left and right, but between change and continuity.”

Żerkowska-Balas says the result signalled a change in Polish politics. “In my view, this change will not end the PO-PiS duopoly for some time, but it may weaken it, forcing these parties to change their optics and really deal with the problems of young people,” she continues.

Our editor-in-chief @danieltilles1 offers five conclusions from yesterday's presidential election first round in Poland – and looks ahead to what it may mean for the decisive second-round run-off in two weeks' time https://t.co/Vzh67U0iV9

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 19, 2025

Szczerbiak acknowledges these cracks, but cautions: “The duopoly is quite firmly based. The nature of that polarisation [between the two parties] is actually quite fundamental.”

He explains that PO and PiS voters have profound disagreements about the nature of the state and so-called cultural-moral issues such as abortion, while also being very distinct socioeconomic and geographic constituencies.

Moreover, young voters are a very volatile electorate and the poor performance of Trzaskowski and Nawrocki among the youth may be due to them being weak candidates more broadly, he adds. Nonetheless, all of the young people that Notes from Poland spoke with expressed their intention to vote in the second round, albeit reluctantly.

“In the second round I think I will vote for Nawrocki, though I really, really don’t want to. A president who participated in football hooligan fights?” says Kotomski, explaining that he still prefers to avoid PO controlling both the presidency and the government.

Likewise, Kundelis says that he will vote “against Trzaskowski” in the second round in the hope that the government falls and early parliamentary elections are held.

“Maybe if the second round were not so close, I would be hesitant about voting,” says Dziurzyński. “Trzaskowski is not a perfect candidate, but ultimately, the alternative is far worse.”

Karolina Rosenberg will also vote for the PO candidate: “Ever since I obtained the right to vote, at the end of the day I have had to pick the lesser evil [in the second round]. It is tiring to think that once again, we could not change things, that none of the other candidates made it to the run-off,” she concludes.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credits: Adrian Zandberg campaign materials, Sławomir Mentzen campaign materials, @partiarazem/Instagram, Silar/Wikimedia Commons (under CC BY-SA 4.0). Collage created by Agata Pyka