Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Daniel Tilles

Over the last month, the main opposition candidate, Karol Nawrocki, has dramatically reduced the gap in polls to the main ruling party’s pick, Rafał Trzaskowski. What has gone wrong for the frontrunner – and right for his challenger?

What a difference a month makes.

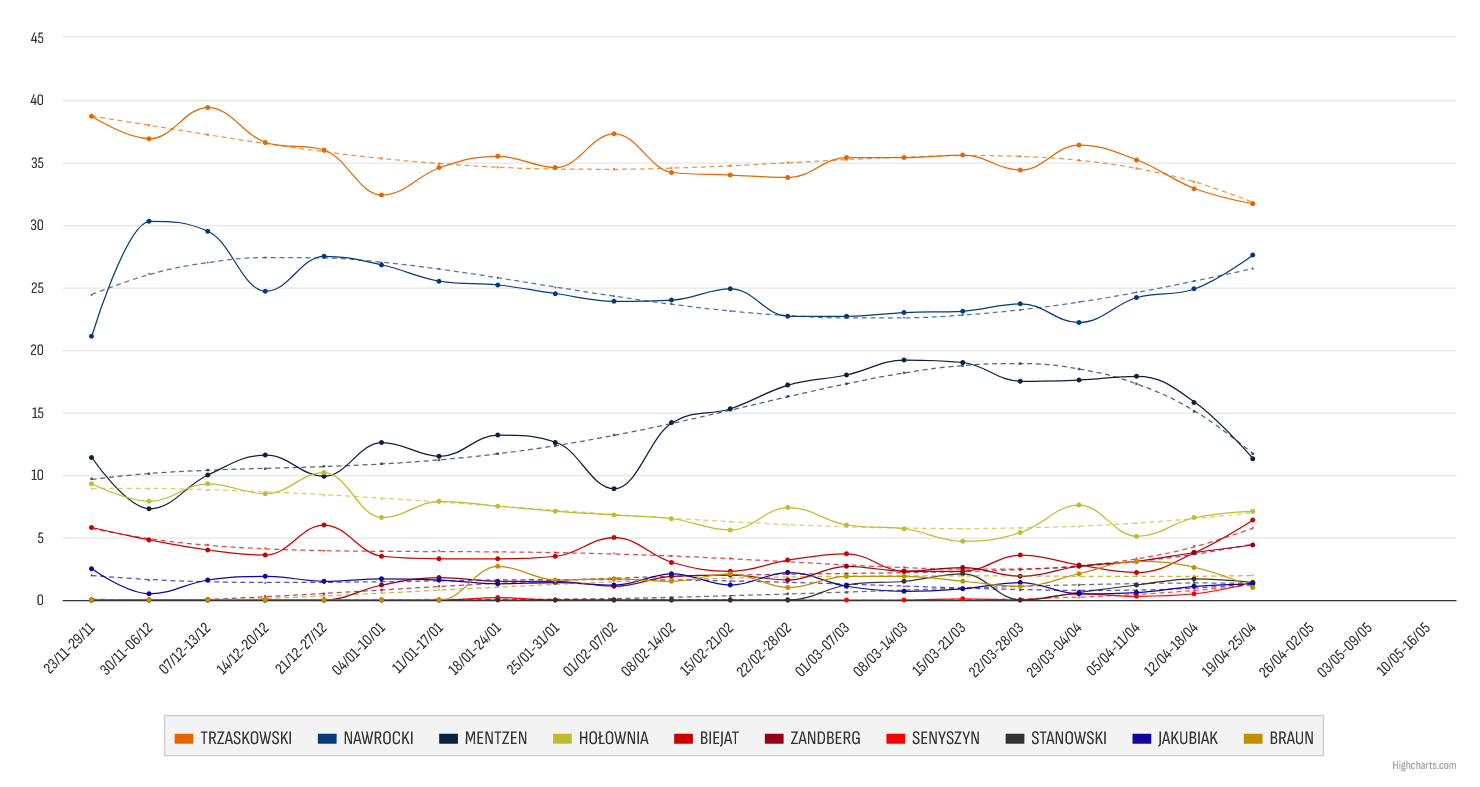

In early April, Poland’s presidential election looked in danger of becoming a procession. Rafał Trzaskowski, the candidate of Poland’s main centrist ruling party, Civic Platform (PO), was riding high in the polls, with average support of around 35-36%, according to averages compiled by Politico Europe, the eWybory website, and Warsaw-based political scientist Ben Stanley.

That placed him 12-14 percentage points ahead of his main rival, Karol Nawrocki, the candidate supported by the national-conservative Law and Justice (PiS), Poland’s largest opposition party, who was on around 22-23%

Back then, the main question was not whether Nawrocki could challenge Trzaskowski for first place, but whether he could even hang on to second (and therefore a spot in the second-round run-off between the top two candidate) amid a strong challenge from Sławomir Mentzen of the far-right Confederation (Konfederacja), whose average support stood at 17-18%.

Weekly average of support in polls for Poland’s main presidential candidates, compiled by eWybory.eu

But, as we wrote in our recent guide to the election, a lot could still change before election day on 18 May – and it has.

By this week, Trzaskowski’s average support in polls had dropped to 32-33% while Nawrocki has risen to around 27-28%, meaning the gap between them has closed to just 4-6 percentage points. Mentzen, meanwhile, has collapsed to 11-12%, seemingly putting him out of the running for a spot in the run-off.

While there are always many factors that influence candidates’ and parties’ waxing and waning popularity, four particular reasons appear to be behind the shift witnessed over the last month.

Trzaskowski’s debate fiasco

It is likely no coincidence that Trzaskowski’s decline in the polls began around the time that he challenged Nawrocki to a one-on-one debate in early April – a decision that sparked a chaotic series of events.

We have already reported on them in detail here, but the result was days of criticism of Trzaskowski for not inviting all his presidential rivals to the debate. That eventually led him to announce less than two hours before the debate was due to start that all candidates were welcome to attend.

In the meantime, conservative broadcaster Republika had organised its own debate, to take place just before Trzaskowski’s and in the same town, to which all candidates were invited. Trzaskowski chose not to attend that one, while Nawrocki did.

Some of Poland's presidential candidates took part last night in one or both of two TV debates organised at the last minute in the same town.

Right up until they began, it was not clear who would participate, resulting in a chaotic five hours of viewing https://t.co/i3SDC2Sm4L

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) April 12, 2025

The entire situation left Trzaskowski looking weak and indecisive, scrambling to respond to events rather than setting the agenda and appearing unwilling to take part in debates that were not under his control.

That impression was reinforced when Trzaskowski skipped another debate organised by Republika a few days later that was attended by Nawrocki and most other candidates (one of whom mockingly placed a cardboard cutout of Trzaskowski on the stage).

Meanwhile, all three debates – the two organised by Republika and Trzaskowski’s own one – saw his rivals focus their attacks on the frontrunner, further undermining his position (especially at the two that he did not attend, and was therefore unable to defend himself).

A fourth debate organised by newspaper Super Express and televised by leading broadcasters took place this week in which all 13 candidates took part. The effect of that event on the polls remains to be seen.

Novice Nawrocki grows into the campaign

When PiS chairman Jarosław Kaczyński made the rather left-field choice to back Nawrocki – the head of a state historical body who has never been a member of PiS and has never stood for public office – for the presidency, many believed he was hoping for a repeat of 2015.

Back then, the PiS chairman picked another relative unknown, Andrzej Duda, as his party’s candidate. For the entire campaign, Duda trailed his PO-backed rival – the incumbent president, Bronisław Komorowski – in the polls before finally snatching a dramatic victory.

This time around, Trzaskowski is not the incumbent (Duda still is), but he is an established figure, the mayor of Warsaw and one of the best-known faces on the political scene.

Nawrocki, by contrast, has had to introduce himself to voters – when he first announced his candidacy in November, one poll showed that 46% of the public did not even know who he was (compared to 2% for Trzaskowski) – and learn on the job how to run a campaign.

Nawrocki has done so energetically, speaking at rallies around the country. Moreover, his decision to appear at all three debates earlier this month – at which he performed strongly – allowed him to present himself to millions of Poles.

As the campaign has gone on, he has grown in confidence, ability and prominence, helping him seize on Trzaskowski’s slip-ups over the last few weeks.

Mentzen’s collapse

Nawrocki’s rise has coincided with Mentzen’s collapse, and the two are no doubt linked, with some right-wing voters switching support from one candidate to the other.

Mentzen likely suffered from skipping both of the first two debates (he argued that he did not want to take part in the “circus” caused by Trzaskowski’s decisions).

But he has also probably been hit by a problem Confederation has previously faced of peaking too early during election campaigns. The same thing happened in the 2023 parliament elections, when the party initially surged in polls, reaching around 14% support, before falling away as polling day approached and eventually winning only 7% of the vote.

Far-right candidate @SlawomirMentzen's rise in the polls has turned Poland's presidential election into a three-horse race

Mentzen has managed to detoxify his party and has benefited from other candidates mainstreaming its positions, writes @danieltilles1 https://t.co/Ql9LihJ7tu

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 28, 2025

One reason behind that may be that the initial appeal of Confederation as an alternative to the dominance of PO and PiS – who have led every Polish government since 2005 – diminishes once there is closer scrutiny of its policies, many of which are not widely popular.

In this particular campaign, Mentzen’s confirmation in late March that he wants all university students to pay tuition fees (currently most study for free) probably had a negative effect, particularly as his supporters are disproportionately young Poles.

Other candidates drawing attention to Mentzen’s hardline anti-abortion views (he opposes allowing pregnancies to be terminated even in cases of rape) also may have harmed him.

A tough-guy campaign

The overriding theme of the election campaign has been security, dictated by the international situation Poland has found itself in: Russia’s ongoing war in neighbouring Ukraine and a campaign of sabotage in Poland itself; the return of Donald Trump to the White House and resultant questions and doubts about alliances; and the continued migration crisis on Poland’s eastern border with Belarus, orchestrated by Minsk and Moscow.

Trzaskowski – an urban liberal with an elitist reputation – is not an ideal candidate for those circumstances. He has certainly talked tough on migration and security (even undertaking military training during the campaign), while also seeking to balance his natural pro-EU inclinations with the need to remain on good terms with Trump.

Poland’s interior minister and the mayor of Warsaw – who is also the main ruling party's presidential candidate – have declared “zero tolerance” for crimes committed by immigrants.

They say foreigners made up 5% of suspected criminals detained last year https://t.co/wnCZqgCsZW

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 11, 2025

But that image always felt rather shallow and fragile – open to challenge by a rival who can more plausibly present himself as the tough guy Poland needs to guide it through these difficult times.

Nawrocki has certainly sought to do so. His campaign regularly shares images of him training in the gym, boxing, running and firing guns.

He has proudly highlighted the fact that he is on a list of those wanted by the Russian authorities due to leading a campaign while head of the state Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) to demolish Soviet-era memorials in Poland. During debates, he has taken a tough, confrontational line.

Jeden dzień, a tyle się wydarzyło. 😉

👉Strzelnica w Lublewie Gdańskim,

👉trening piramida,

👉Światowy Dzień Kociewia w Starogardzie Gdańskim i Tczewie.Zachęcam do treningu #piramida.

🕐W 23 minuty:

55 x klatka 90 kg

55 x martwy ciąg 90 kg

55 x pompki

55 x podciąganie

55 x… pic.twitter.com/UsdSCb61mJ— Karol Nawrocki (@NawrockiKn) February 11, 2025

That messaging may now be starting to chime with voters. Meanwhile, some in PO may be regretting the decision, in party primaries that took place last year, to choose Trzaskowski as their presidential candidate rather than the alternative option of Radosław Sikorski, the tough-talking current foreign minister and former defence minister.

Sikorski would certainly have come with a lot of negative baggage, and may have performed no better overall than Trzaskowski. But he seems better suited to the kind of campaign that has emerged.

He himself appeared to stick the boot into Trzaskowski last month, commenting that, unlike Trzaskowski, he would have attended the debates organised by Republika because “appearing on right-wing TV would be rather useful”.

Whereas Trzaskowski is not a natural speaker and debater, Sikorski thrives on the confrontational cut-and-thrust of campaigning.

"I advise President Duda against volunteering to be the Chamberlain of this war," said Poland's foreign minister @sikorskiradek after the president called on Ukraine to "make compromises" in order to achieve peace with Russia https://t.co/qQsGFSnEL3

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) April 25, 2025

What’s next?

It is important to remember that, although Nawrocki has risen rapidly in the polls, a) he remains behind Trzaskowski in the contest for the first round, and b) polling for a likely second-round run-off between the two consistently shows Trzaskowski beating his rival (though far fewer such polls have been conducted than for the first round).

Trzaskowski, therefore, remains the favourite to become Poland’s next president. But momentum can be a powerful thing in election campaigns, as Duda showed in 2015 with his late charge to the presidency. And that momentum is certainly with Nawrocki at the moment, two-and-a-half weeks before the election.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Silar/Wikimedia Commons (under CC BY-SA 4.0)

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.