Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

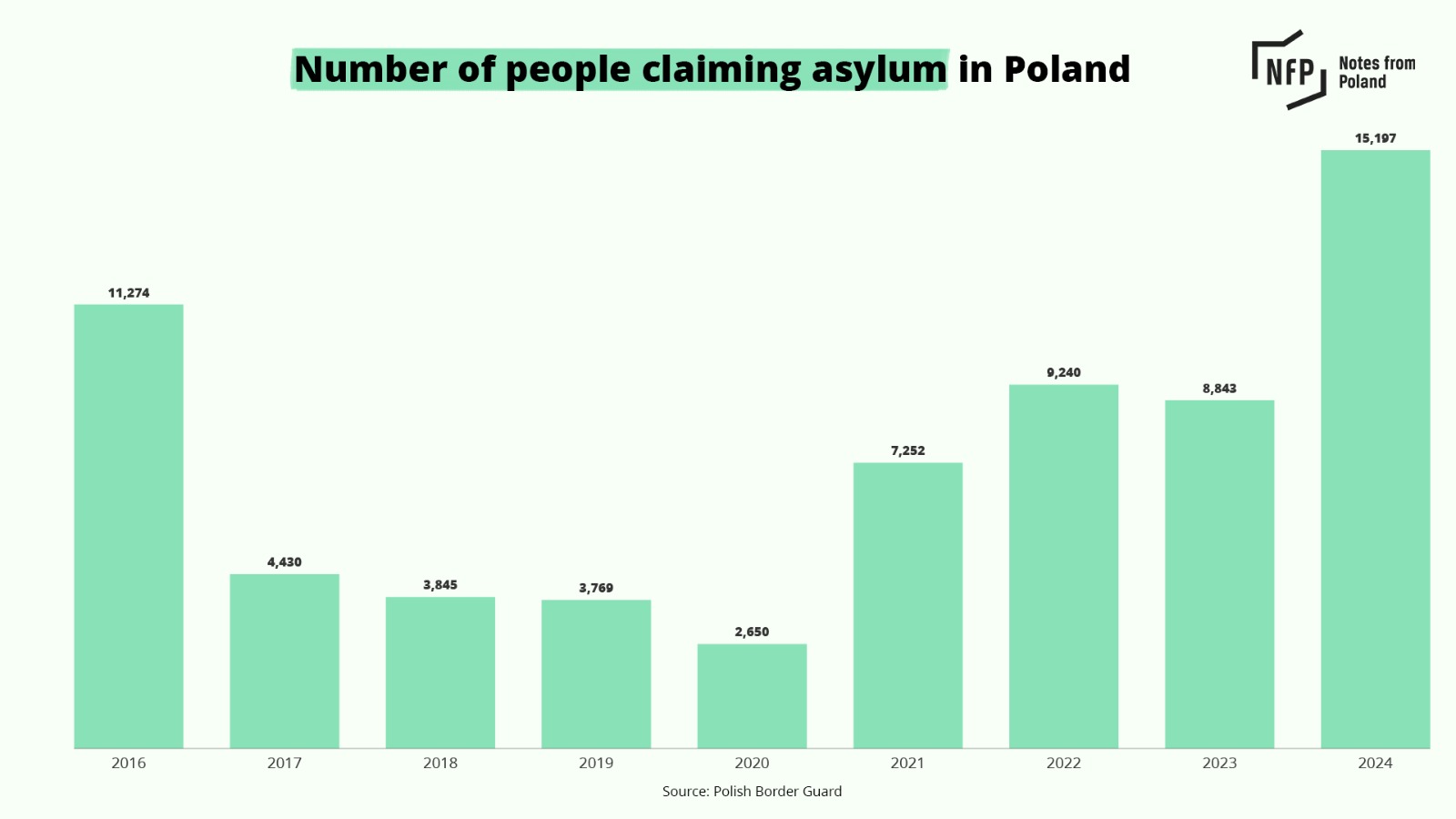

Over 15,000 people applied for asylum in Poland in 2024, 72% more than a year earlier and the highest annual figure recorded by the Polish border guard, whose data go back to 2016.

A large proportion of the rise was accounted for by an increase in asylum claims from Ukrainians compared to 2023. But there was also a surge in applications from Ethiopians, Eritreans and Somalis who entered Poland from Belarus.

Border guard data show that 15,197 people submitted applications for international protection in Poland last year, up from 8,843 in 2023 and higher than the previous record of 11,274 in 2016. (Millions of refugees from Ukraine arrived in 2022, but most were granted a different status from normal asylum.)

Last year, 6,283 people from Ukraine applied for international protection through normal channels. That was over almost four times as many as the figure of 1,662 in 2023.

After Ukrainians, the largest number of applicants last year were from Belarus (3,663) and Russia (823). They were followed by the East African trio of Ethiopia (515), Eritrea (505) and Somalia (486).

The number of applicants from those latter three countries combined last year (1,506) was over 12 times higher than in 2023 (123).

Those figures came amid an intensification of the crisis on Poland’s border with Belarus, where tens of thousands of migrants and asylum seekers – mainly from Africa, Asia and the Middle East – have been trying to cross with the encouragement and assistance of the Belarusian authorities.

The Belarus border crisis began in 2021, but the first half of last year saw a renewed surge in the number of attempted crossings. The border guard’s report for 2024 notes that there was a 2,081% annual increase in the number of asylum claims filed at its facility in Czeremcha on the Belarus border.

The data also show that, whereas applications from Ukrainians, Belarusians and Russians were mostly submitted at the border guard station in Warsaw, those from Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia were most often filed at the Belarus border, as were applications from Syrians, Sudanese, Yemenis and Afghans, among others.

Germany plans to open a new "departure centre" on the border with Poland that will speed up the deportation of asylum seekers who have submitted claims in other EU member states but then come to Germany https://t.co/GCdNOoadcF

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 17, 2025

“After three years of crisis on the border with Belarus, foreigners are well aware that if they are caught, it is necessary to ask for asylum,” Daniel Boćkowski, a security expert at the University of Białystok, told news website Wirtualna Polska.

“Such advice appears on online migrant forums: to ask for asylum if they fail to cross, get injured or physically exhausted, because then there is a chance that the [security] services will not push them back to Belarus,” he added.

Poland has for years – both under the current and former government – pursued the controversial practice of “pushing back” some people who cross the border.

Poland carried out over 6,000 so-called "pushbacks" of migrants who crossed the border from Belarus between July 2023 and January 2024.

It is the first time the government has released data on the practice, which has been criticised by human rights groups https://t.co/DA5mCB7vAC

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 7, 2024

This has happened even in cases where people have claimed asylum in Poland, a practice condemned by human rights groups and deemed unlawful by Polish courts.

Wirtualna Polska suggests that the higher number of asylum claims being submitted last year may be because of such rulings, which have put pressure on border guards to accept appplications.

In response to last year’s surge in crossings, the Polish government implemented new security measures on the border, including introducing an exclusion zone and easing rules on the use of firearms by officers. There was subsequently a 50% fall in attempted crossings in the second half of 2024.

The number of attempted crossings from Belarus to Poland fell by over 50% in the second half of last year after the Polish government implemented tougher new measures to combat irregular migration, border guard data obtained by @notesfrompoland show https://t.co/fXfmgHIIBS

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) January 10, 2025

In the autumn, Prime Minister Donald Tusk proposed an even tougher new migration strategy, including suspending the right to apply for asylum for those who cross the border irregularly. He argues that existing rules were not designed for the recent phenomenon of “weaponised migration“.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has warned Poland that such a move would violate European and international law. However, Tusk has claimed that other EU leaders have been receptive towards the idea.

The Polish government also notes that many of those who apply for asylum after being caught crossing the border leave Poland for other EU countries before their application is assessed.

The state Office for Foreigners reports that last year 3,400 asylum proceedings were discontinued, usually because the person had left the country. This happened most often in the cases of Eritreans (460 people), Somalis (440) and Syrians (390), reports Wirtualna Polska.

The UN @Refugees agency has warned Poland that its planned toughening of migration and asylum rules does "not comply with international and European law".

The proposals include suspending the right to claim asylum by those who irregularly cross the border https://t.co/aTNcmUHvZc

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 5, 2025

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: MSWiA (under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 PL)

Agata Pyka is a former assistant editor at Notes from Poland. She specialises in Central and Eastern European affairs, cybersecurity, and investigative reporting. She holds a master’s degree in political communication from the University of Amsterdam, and her work has appeared in Euractiv, the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), and The European Correspondent, among others.