Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Stuart Dowell

For Anna Odi, home is a place most would consider unimaginable. She has lived her entire life within the grounds of Auschwitz, the former German-Nazi concentration camp, surrounded by its dark history, in a former SS administration building that now forms part of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum.

At 68, Anna refers to herself as “the last prisoner of Auschwitz”, not because she endured its horrors firsthand, but because her life has been shaped, even dictated, by the camp’s legacy.

“I think I am simply a hostage to the stories of people who experienced this hell,” she says. “I continue what my parents started. I owe it to the victims.”

Anna’s connection to Auschwitz began before her birth. Her parents, Mira and Józef, both survived concentration camps.

Mira, a Polish immigrant to France, found herself trapped in Warsaw when Germany invaded Poland during a visit to her relatives in 1939. She was arrested in 1941 by the Gestapo for her involvement in the underground resistance and endured 18 months of torture and interrogation in Pawiak prison.

A new biography tells the extraordinary story of Polish WWII resistance fighter Elżbieta Zawacka.

She operated as an undercover courier in occupied Europe, was the sole female member of an elite Polish paratrooper group, and served in the Warsaw Uprising https://t.co/SUlu3cFUgK

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 17, 2024

Mira was then deported to concentration camps, including Majdanek, Ravensbrück and Buchenwald. Near the end of the war, she escaped a death march and found shelter with a German family, who risked their lives to hide her. After the war, Mira settled in Upper Silesia.

Józef, a native of Upper Silesia, was only 16 when he joined the Polish Army at the outbreak of the war, a decision that severed ties with his German-loyal father. Captured first by the Soviets and then by the Germans, he endured torture in a prison in Mysłowice before being sent to Auschwitz as a political prisoner.

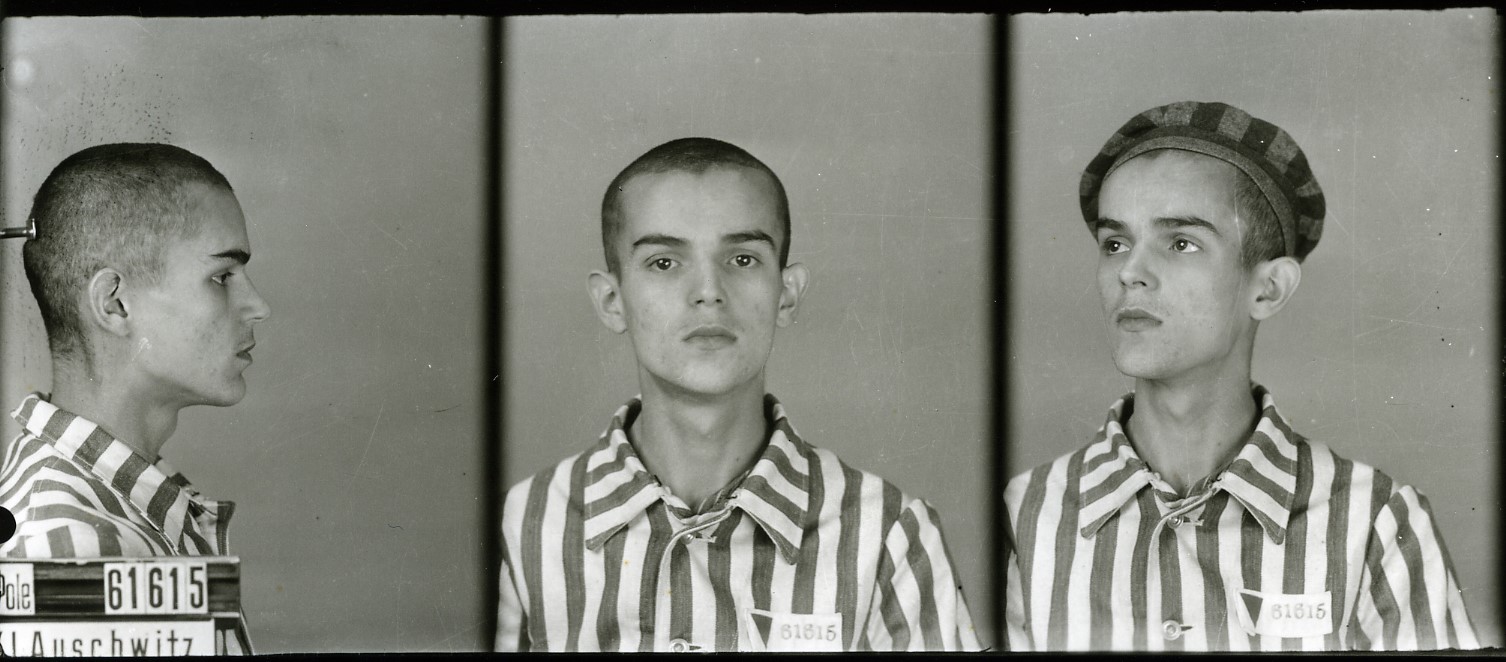

Marked with the number 61615, Józef performed forced labour, disinfecting prisoners’ uniforms and sorting belongings taken from those sent to their deaths. He survived brutal beatings and near-starvation before being transferred to Ebensee, a subcamp of Mauthausen, where he was liberated in 1945 by Allied forces.

Auschwitz prisoner photographs of Józef Odi (image credit: Archives of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum)

After the war, Mira and Józef met in Upper Silesia. Their shared experiences of survival brought them together, and they soon married. However, the immediate post-war period left them with few options for housing or work.

When Józef learned that volunteers were needed to guard and preserve the site of Auschwitz, he accepted the role, and Mira joined him soon after to work as a guide with fluency in French.

Initially, the family lived in the so-called “Gate of Death” gatehouse at Birkenau, where Anna’s eldest sister was born in 1946. This notorious building, which prisoners once passed on their way to the gas chambers, became the first home for the Odi family.

Their neighbours included former camp prisoners, whose reasons for returning to Auschwitz were shaped by both practical needs and a deep sense of duty. After the war, Poland faced severe housing shortages, and the camp provided immediate shelter for survivors, many of whom later took on roles as guides, archivists and custodians of memory at the newly established Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum.

The gatehouse at Birkenau where the Odi family lived (image credit: Michel Zacharz/Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 2.5)

Anna was born in 1956 in a hospital in Oświęcim – the town in which Auschwitz was built – but just days after her birth her parents took her home to the camp. Her early life was marked by a unique blend of normality and historical weight.

Her father often cooked for the family and their neighbours, creating a sense of warmth amid the sombre environment. Holidays were observed with care, and her parents went to great lengths to shield their children from their home’s dark past.

Later, they moved into the former SS administration block at Auschwitz I, a grim building that once housed the offices of camp overseers. “It was a 40-metre flat, converted from an SS office,” Anna recalls. “Now, most of the building is used for museum offices, and only a few flats remain.”

The early post-war years brought challenges. The camp was not yet a museum but a desolate and decaying site. Looters frequently targeted the barracks, seeking valuables or simply scavenging materials. Survivors like Józef and Mira took on the monumental task of preserving the remnants of Auschwitz.

People first started to visit the camp soon after its liberation in 1945, initially in an informal capacity. More arrived in 1947, when the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum was officially established.

Mira, as a guide fluent in French, welcomed the first groups of visitors. Anna describes them not as tourists but rather pilgrims seeking to understand what had happened. Józef, meanwhile, worked tirelessly to protect items like piles of shoes, glasses, and letters that memorialised the victims’ final moments.

They both protected documents, personal belongings and the physical structures that bore witness to unimaginable atrocities.

Growing up behind the barbed wire, Anna had no frame of reference for how extraordinary her childhood was. Interactions with former prisoners visiting her parents were frequent, and they left a lasting impression on her.

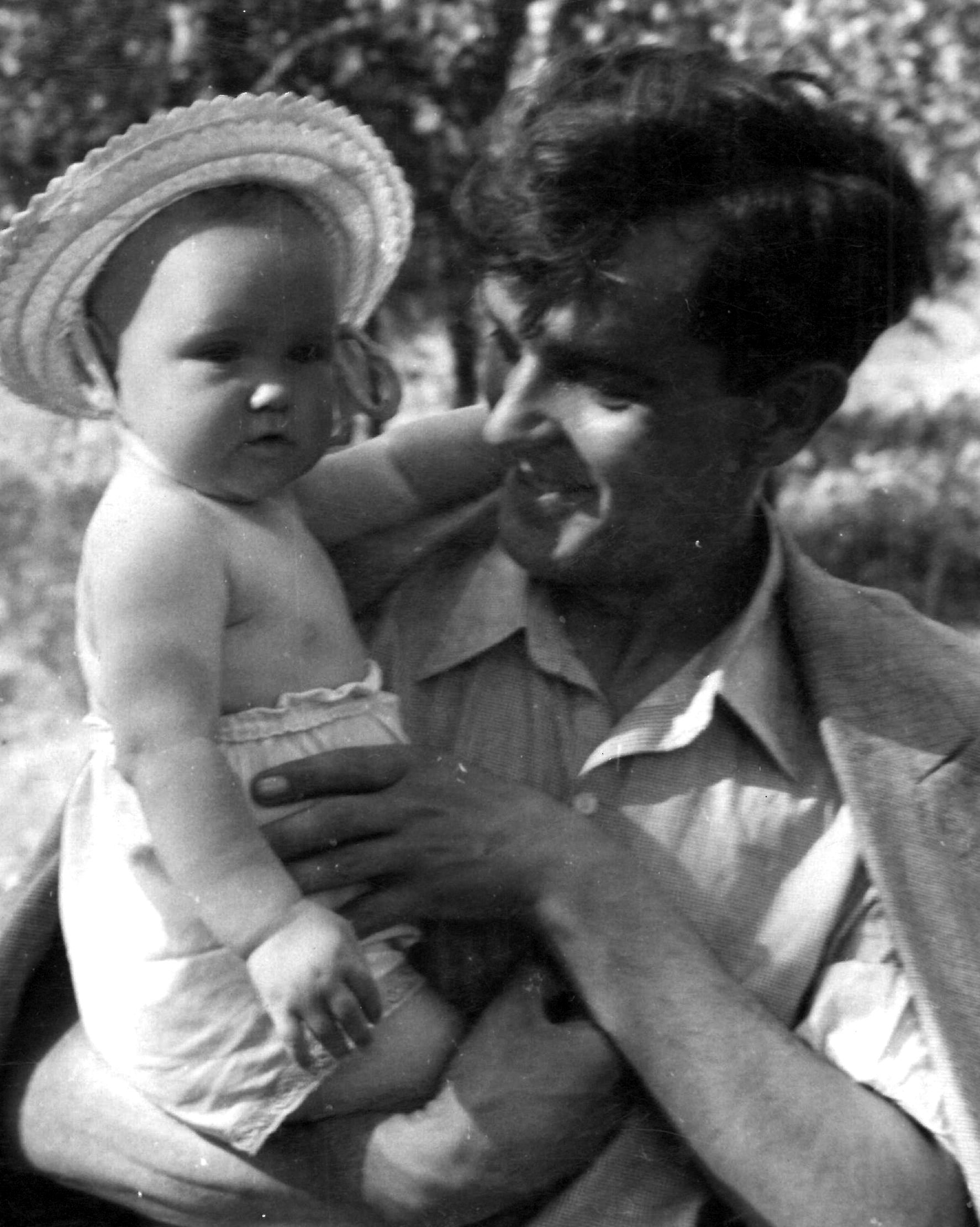

Anna with her father, Józef, 1957 (image credit: Wydawnictwo Bellona, press materials)

“These were my first encounters with history,” Anna recalls, “even if I didn’t fully understand it at the time. They were like aunts and uncles to us, sharing their stories over tea or during quiet evenings.”

“I didn’t realise the tragedy that had happened here,” she says. “This was just my backyard.”

Despite the weight of history, Anna’s parents tried to give her and her sisters a normal upbringing. They built sandboxes for the children to play in and hosted Christmas celebrations. Yet Auschwitz’s grim reminders were never far away.

Anna vividly remembers a school assignment that made her realise how different her life was. “I was asked to draw the view from my window,” she says. “I chose the gallows [where former camp commandant Rudolf Höss was hanged in 1947]. It was just easier, some horizontal and vertical lines, and you’re done.”

Her childhood playmates included the children of other former prisoners who lived in the camp’s administrative buildings. Together, they turned Auschwitz into their playground. They raced bikes around the grounds, built sandcastles near the crematorium, and sledded on snowy mounds outside the former camp commandant’s office.

The gallows on which Rudolf Höss was hanged (image credit: Pimke/Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 3.0)

One of her closest friends was a girl named Ania, whose family lived in the villa occupied by Rudolph Höss and his family during the war. The same garden where Höss’s children once played became a refuge for Anna and her friends.

Not all of her friends were comfortable with the site’s history. Anna recalls her classmates being hesitant to visit her home. “Some of them were afraid,” she explains. “They’d heard stories about the camp and thought there might be ghosts.”

It was not until Anna started asking questions that her parents began to reveal their past. “They didn’t tell me everything at once,” she says. “But over time, I learned about the horrors they had endured.”

Anna’s parents carried deep scars from their wartime experiences. Mira lost her family during the war and spent her life grieving the parents she could never see again. Józef, a devout Catholic before the war, lost his faith entirely.

“He would ask, ‘Where was God when people were being burned in crematoria?’” Anna says.

Despite their suffering, Mira and Józef chose to dedicate their lives to preserving Auschwitz. Alongside other survivors, they gathered documents, personal belongings and artifacts left behind, laying the foundation for the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum.

An archive in Germany has returned personal items confiscated from Polish concentration camp prisoners to their families.

The objects, which included watches, jewellery, letters and photographs, were handed over at a ceremony in Warsaw https://t.co/a3e0nLDfP0

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) September 13, 2024

This work was not without its challenges. The early volunteers lacked resources and faced resistance from some locals, who viewed the camp as a source of shame rather than a place of remembrance. Yet, the pair persisted, driven by a sense of moral duty.

“In this tragic place where so many people were killed, my parents gave new life,” Anna says. “They started a mission to save history from oblivion.”

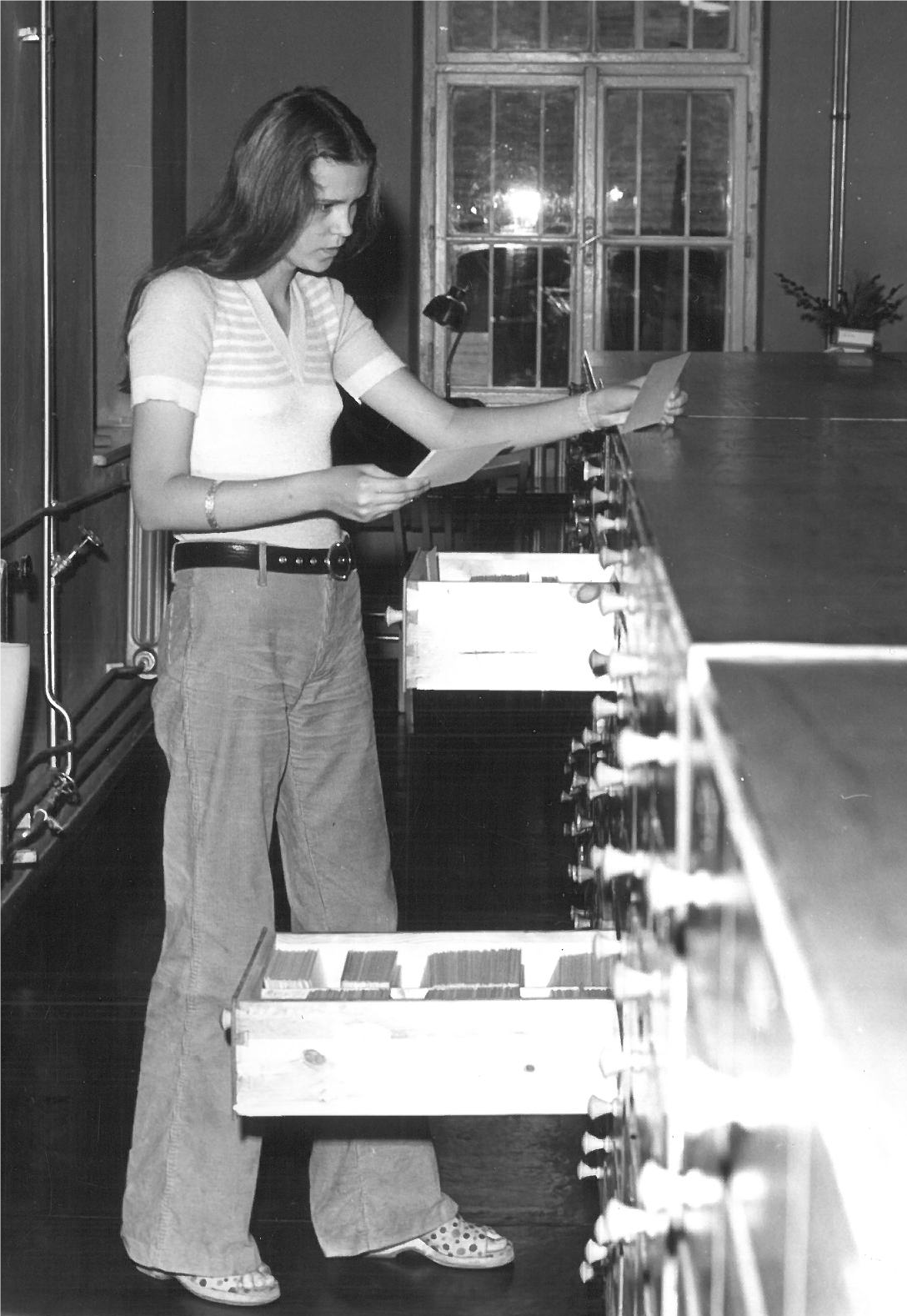

In 1975, fresh out of high school, Anna began working at the museum. Initially, she had planned to study law but decided against it, feeling drawn to the work her parents had started at Auschwitz.

Her first role at the museum was as a guide, showing visitors around the camp and explaining its harrowing history. However, Anna soon realised that the work was too emotionally taxing for her. She found it difficult to speak about the camp’s horrors so directly and decided to move to a different role.

Anna Odi in her first year working at the museum (image credit: Wydawnictwo Bellona, press materials)

“It was my first and last job,” she says. Starting in the archives, she later moved to the collections department, where she catalogued items like striped uniforms, letters and drawings. “Behind every document or object is a human drama, a story that must be told,” she continues.

She treated each artifact – from letters smuggled out of the camp to shoes left behind in the barracks – as a vital piece of history, often reflecting on the lives of the people behind them.

Anna saw her work as that of a detective, piecing together fragments of lives lost. “The work was challenging but rewarding,” she explains. “Every object has a story, and it was my responsibility to ensure those stories are not forgotten.”

While she initially struggled with the emotional weight of her new responsibilities, Anna came to view her work in the archives and collections departments as a mission. “This land is soaked with the blood of victims,” she says. “It demands truth. It requires us to shout the truth about what happened here to the world.”

Anna often speaks about the presence she feels of those who perished at Auschwitz. “It’s not a haunting,” she says, “but a guidance. I feel they help me uncover their stories, connecting photos to names and objects to lives. It’s as if they want to ensure they’re not forgotten.”

A display of victims’ shoes in the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum (image credit: Bibi595/Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 3.0)

While many former residents have moved away, Anna has stayed. Her flat, once shared with her parents and sisters, became emptier as her family left, one by one. Today, she is one of the last remaining residents in the building, which is now mostly converted into museum offices.

“I cannot imagine living anywhere else,” she says. “This place is part of me.”

Anna’s extraordinary life was the subject of The Last Prisoner of Auschwitz, a book by Nina Majewska-Brown. “I am grateful this book was written,” Anna says. “May there never be a shortage of people willing to speak and write about Nazi crimes and their victims.”

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: private archive of Anna Odi