By Stuart Dowell

The opening of the Wedel Chocolate Factory Museum in Warsaw – housed in a building shaped like a colossal chocolate bar – promises to sweeten the city’s cultural landscape and take visitors on a sensory tour of Poland’s oldest chocolate company.

This 200 million zloty (€47.5 million) investment, the biggest in the more than 170-year history of the company, allows visitors to taste and smell an array of confectionery, as well as see how popular Wedel products, such as Ptasie Mleczko and Torcik Wedlowski, are made.

However, the museum makes the claim to be more than just a Willy Wonka-style celebration of sugar and chocolate. It stands as a tribute to migration, perseverance and, ultimately, a practical form of patriotism.

The Wedel Chocolate Factory (left) and the Wedel Chocolate Factory Museum (right) (photo credit: E.Wedel, press materials)

The rich, gooey filling of the company’s story is the legacy of three generations of the Wedel family – Karl, Emil and Jan. The family initially migrated from Germany to partitioned Poland and transformed a small confectionery shop into a symbol of Polish entrepreneurship.

From its modest beginnings in 1851, Wedel grew to become a favourite among sweet-toothed Poles, reaching its golden age in the 1930s under the ownership of the founder’s grandson Jan Wedel.

The centrepiece of this chocolate empire was the renowned Wedel Chocolate Lounge on Szpitalna Street in Warsaw, a favourite hangout for prominent individuals such as the writers Bolesław Prus and Henryk Sienkiewicz.

The present-day Wedel drinking chocolate lounge on Szpitalna Street, Warsaw (photo credit: Adrian Grycuk/Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 3.0 PL)

But this golden age came to end with the outbreak of World War Two, transforming the Wedel story into a tale of survival, charity and adaptability, followed by the difficulties of the postwar communist era.

A chocolatier in Congress Poland

The Wedel saga started in 1845 with the arrival in Warsaw of Karl Ernst Wedel, a German confectioner from Berlin. Warsaw at the time was a city in the Russian Empire, and Wedel was one of many enterprising Germans who recognised potential in the expanding market in what was then known as Congress Poland.

Following a brief collaboration with local confectioner Karol Grohnert, Wedel opened his own company in 1851 at 12 Miodowa Street. There, he created a wide range of products, such as crème caramels, chocolate bars, chocolate figures and drinking chocolate.

At this time of year, Poles are no different from many other nations when it comes to indulging their sweet tooth.

Here's a pick 'n' mix of some of the delicacies that will be enjoyed throughout Poland in the coming days and beyond.https://t.co/mi09y9kivq

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 18, 2019

Since confectionery was not thought of as just an opulent treat at the time, his products were frequently marketed as remedies for common ailments.

Rather than pursue quick profits, Karl took a long-term approach to the business and tried to maintain a close relationship with his staff and clients, which he believed was essential to guarantee quality.

He also demonstrated a deep awareness of his new home, showing compassion and empathy for Poles even though he was a recent immigrant. For example, Karl limited Wedel production during the mourning period that followed the execution of Polish national hero Romuald Traugutt in 1864.

Karl gave many Polish youngsters financial support for private education so that they would not have to endure Russian indoctrination at public schools. He also won over his Polish clientele by pricing his goods in Polish zlotys, even though at the time the official currency was Russian roubles.

Sorry to interrupt your reading. The article continues below.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Karl eventually passed the business on to his son Emil, who was born in Berlin in 1841 and grew up bilingual, fluent in both German and Polish. This linguistic duality reflected the Wedel family’s growing integration into Polish society. Emil married Eugenia Böhm, a Pole, and their three children were raised to speak Polish.

Under Emil’s leadership, the Wedel brand flourished with more products and modernised production methods.

A major change that can still be observed today was the introduction of the now-iconic “E.Wedel” signature on each chocolate bar, which was a necessity as Wedel’s renown was so great that its products were being counterfeited by unscrupulous competitors.

However, despite the success, Emil, like his father, was reluctant to expand excessively. He remarked that he had “no desire or intention to enlarge the factory because he really wanted to know all the employees”.

Emil Wedel (photo credit: E.Wedel, press materials)

One major development was the purchase of a large building on Szpitalna Street in Warsaw. At the rear was a production site, upstairs were the family’s living quarters, and on the ground floor was the capital’s most famous drinking chocolate lounge, which still operates today.

The golden age of Wedel

By the time Emil handed the business over to his son Jan in the early 20th century, Wedel had transformed from a local confectionery into a national institution.

Jan embodied the Wedel family’s complete assimilation into Polish society. He saw himself not as a businessman of German descent, but as a Polish entrepreneur committed to his homeland’s prosperity.

Jan’s appointment as head of the company in 1923 marked the beginning of Wedel’s golden age. Under his leadership, the company became a symbol of modernity in interwar Poland.

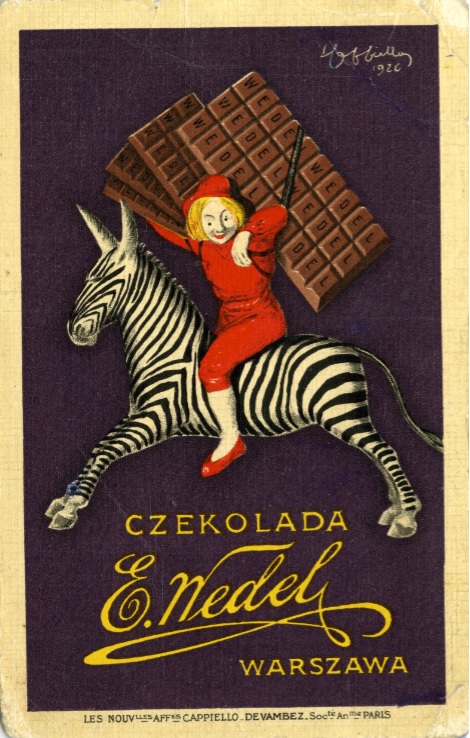

Wedel’s advertising took a leap forward with the introduction of its famous logo – a boy riding a zebra while holding chocolate bars – designed in 1926 by Italian poster artist Leonetto Cappiello. The logo still sits proudly in neon atop the building on Szpitalna Street.

The Wedel logo, featuring a boy on a zebra (photo credit: Leonetto Cappiello/Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 4.0)

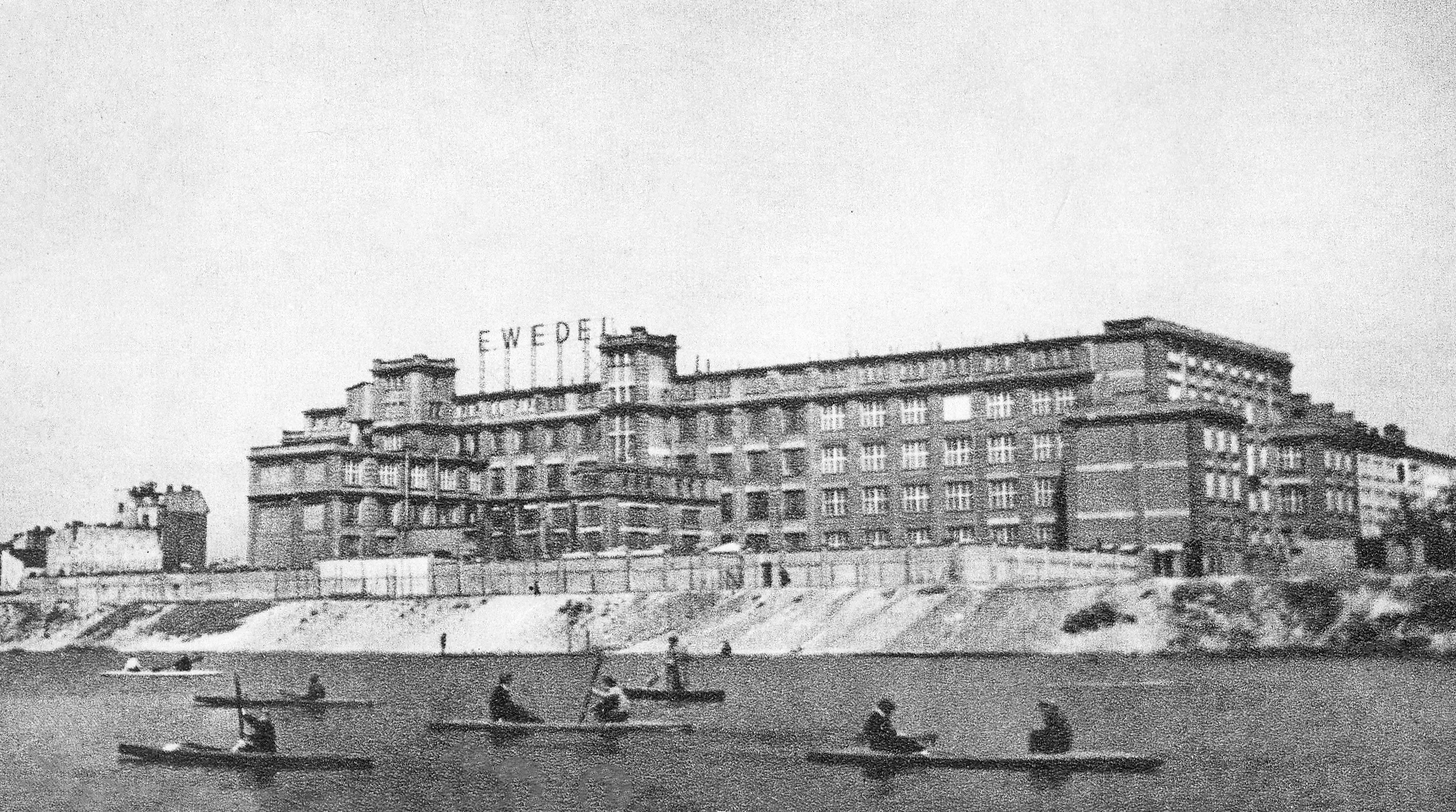

In 1927, Jan started the construction of a state-of-the-art factory in Warsaw’s Kamionek district, which still stands today and acts as the backdrop to the new museum.

The new factory was equipped with staff amenities that were progressive for the time: a nursery and kindergarten for employees’ children, medical and dental surgeries, and even a bathhouse for workers.

The company organised summer camps for employees’ children, supported a workers’ sports club, and even set up a company theatre.

The Wedel factory in Warsaw’s Kamionek district during the interwar (photo credit: unknown author/Wikimedia Commons, under public domain)

It was under Jan’s leadership that in 1936 Wedel launched Ptasie Mleczko (in English, Bird’s Milk), a fluffy marshmallow cloaked in chocolate that remains an icon of Polish confectionery.

During the interwar, Wedel-branded delivery trucks became a common sight on Warsaw’s streets, and the company even acquired an aeroplane to swiftly transport sweets to the Polish seaside.

Jan introduced vending machines at the entrance to Warsaw’s Skaryszewski Park. He also opened elegant, modern Wedel stores across the whole of Poland, from Warsaw and Kraków to Lwów and Gdynia.

Wedel products even made it to as far as Japan, while the company also had a store in Paris and its chocolates were available in Polish embassies across the globe.

The Wedel-owned residential building at 28 Puławska Street, Warsaw (photo credit: Adrian Grycuk/Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 3.0 PL)

Jan commissioned renowned architects to design Wedel-owned buildings. A striking example is the still-standing modernist residential building at the corner of the Puławska and Madalińskiego streets in Warsaw.

A hub of wartime resistance

Yet the outbreak of World War Two in September 1939 would present Jan and the Wedel company with their greatest challenge yet.

As the German occupation tightened its grip on Poland, Jan was confronted with a difficult choice: sign the Volksliste and declare himself a German national, or refuse and face severe consequences.

Despite the significant risks, including the loss of his villa in Konstancin, Jan chose to remain loyal to his Polish identity, refusing to sign the list.

Jan Wedel (photo credit: E.Wedel, press materials)

Wedel foresaw the arrival of war and took steps to prepare for it, prudently stocking the factory with tonnes of cacao and sugar, ensuring that production, and therefore employment, could continue despite the harsh restrictions imposed by the Germans.

Even though the company was forced to produce confectionary exclusively for the German occupiers, keeping the factory open meant it could serve as a lifeline for the people of Warsaw.

Jan opened the company’s warehouses, distributing food to residents during the September campaign of 1939, saving lives from starvation. His factory became a hub of resistance, covertly supporting the Polish Home Army and other underground activities.

Wedel managed to smuggle supplies to prisoner-of-war camps and provide food for the impoverished, including children from Janusz Korczak’s orphanage.

Poland today marks the 80th anniversary of the formation of the Home Army, a resistance movement that emerged during the Nazi-German occupation and which is believed to have been the largest such underground force in Europe https://t.co/9sKsfVskrg

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 14, 2022

Jan secretly increased employment at the factory, despite official restrictions, and supported Warsaw’s artists and intelligentsia, providing them with essential supplies. His factory also became a refuge during the Warsaw Uprising, with supplies hidden from the Germans and a makeshift kitchen run by his sister, Zofia, feeding the insurgents.

In the final days of the war, as the Germans prepared to demolish the factory, Wedel’s workers sabotaged the demolition efforts, ensuring the factory’s survival.

Wedel in the modern era

Although Jan was initially involved in restarting production after the war, he was eventually fired by the new communist authorities from the very factory that was his life’s work.

Forbidden from entering the premises, he was left heartbroken, observing the factory each day from across Kamionek Lake until his death in 1960.

First Secretary Edward Gierek visits the nationalised Wedel factory (ZPC 22 Lipca) during communist rule (photo credit: unknown author/Wikimedia Commons, under public domain)

The company was nationalised in 1949 and renamed ZPC 22 Lipca, absorbing three other confectionery factories. Despite its nationalisation, the Wedel brand retained its reputation for quality, becoming a cherished name even under communist rule.

After the fall of communism in 1989, the company was sold to PepsiCo. However, the new American owners preferred to focus on salty snacks rather than chocolate, even stacking rows of potato crisps in the iconic store on Szpitalna Street.

After further corporate shuffling, including a period under British chocolate manufacturer Cadbury, the company was purchased in 2011 by Lotte, a Japanese-Korean conglomerate, who own it to this day.

According to Robert Zydel, director of the E.Wedel Chocolate Factory, the idea for the museum originated from a group of Wedel employees who wanted to honour the company’s heritage while offering a new, interactive way for visitors to engage with the world of chocolate.

Interior of the Wedel Chocolate Factory Museum (photo credit: E.Wedel, press materials)

“This place is the result and at the same time a continuation of our commitment to preserving the heritage of the E.Wedel brand and enjoying the potential of chocolate,” he says.

The museum claims to offer a truly immersive experience. A policy of “please DO touch the exhibits” accompanies an experience in which visitors will not only observe but also participate in the chocolate-making process.

Activities include designing your own chocolate bar, sampling fresh delicacies, and even creating your own packaging for the iconic Ptasie Mleczko.

The viewing terrace on the 6th floor – offering views of Kamionek Lake and the Warsaw skyline – gives visitors the chance to reflect on what Karl Wedel would have made of the dramatic changes that have taken place in Poland’s capital since he founded his chocolate shop 173 years ago.

Main image credit: Adam Stepien / Agencja Wyborcza.pl