By Katarzyna Skiba

Poland’s new government and parliament boast record numbers of women. But does this represent genuine change or is it just window dressing for an administration still dominated by men?

In July, Donald Tusk, then Poland’s main opposition leader, appealed to Poles to join him on a large anti-government march that would take place on 1 October, two weeks ahead of parliamentary elections.

He began his speech by invoking the recently reported scandal of a woman in Kraków, Joanna, who had been searched by police in hospital after taking abortion pills.

Police intervention against a woman hospitalised after taking abortion pills has caused anger.

Officers reportedly surrounded the woman, who was asked to strip, and confiscated her devices as they investigated if someone helped her terminate her pregnancy https://t.co/5SrkvNeMWs

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) July 19, 2023

Joanna’s case was another example of women being “humiliated” by the “aggressive, oppressive presence of PiS”, the national-conservative ruling Law and Justice party, said Tusk, who praised Joanna’s “courage in speaking up”. The October elections would give Poles the chance to remove this “evil” from power, he declared.

Tusk’s march, attended by hundreds of thousands, was a huge success and helped add to the momentum that brought his coalition to power at the elections. But Joanna did not attend the event; she told the media that no one had invited her.

“My story was exploited to build political capital and for pre-election games,” she said at the time. “It was not about me or women’s reproductive rights; the most important thing was the fight with PiS.”

A large opposition march has passed through Warsaw, two weeks ahead of parliamentary elections.

"We are moving towards a Poland that is open, tolerant, European," declared the city's opposition mayor @trzaskowski_ https://t.co/2hUP3a8YXY

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 1, 2023

Speaking to Notes from Poland now, a few weeks into the rule of Tusk’s government that took office in mid-December, Joanna says she is pleased that PiS has been removed from power but remains sceptical about the new administration.

“I approach them with a great deal of distrust and I am far from optimistic,” says Joanna.“I would be able to survive the fact that the current prime minister built his political capital on my personal tragedy if the theatrical pre-election rhetoric was replaced by honesty and reliability”.

“The new government now has all the tools to liberalise the abortion law and decriminalize abortion assistance. So what are we waiting for?” she asks.

Record number of women in parliament

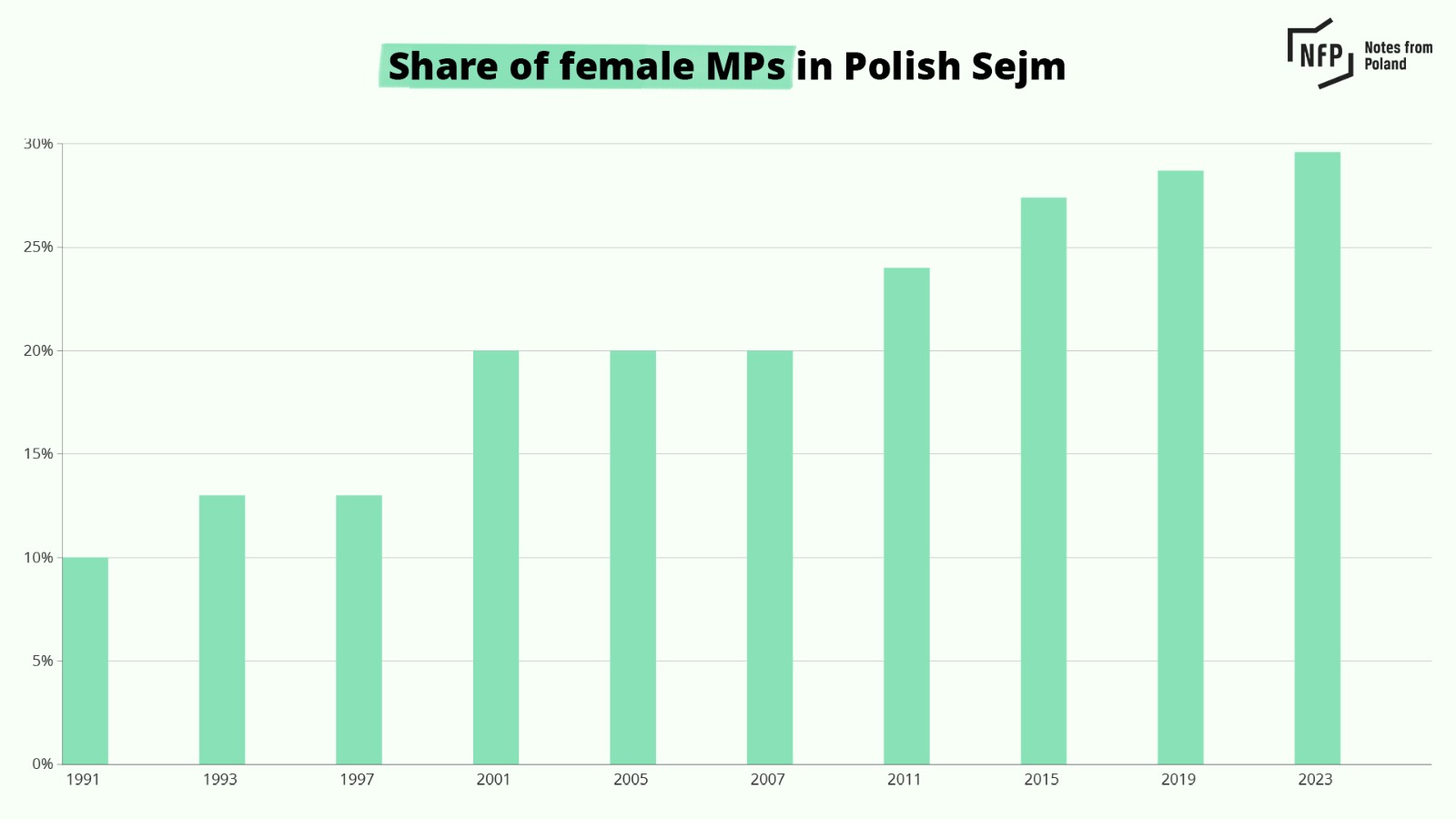

Poland’s new government and parliament contain more women than ever before. Almost 30% of MPs are now female, up from 20% two decades ago and 10% in 1991.

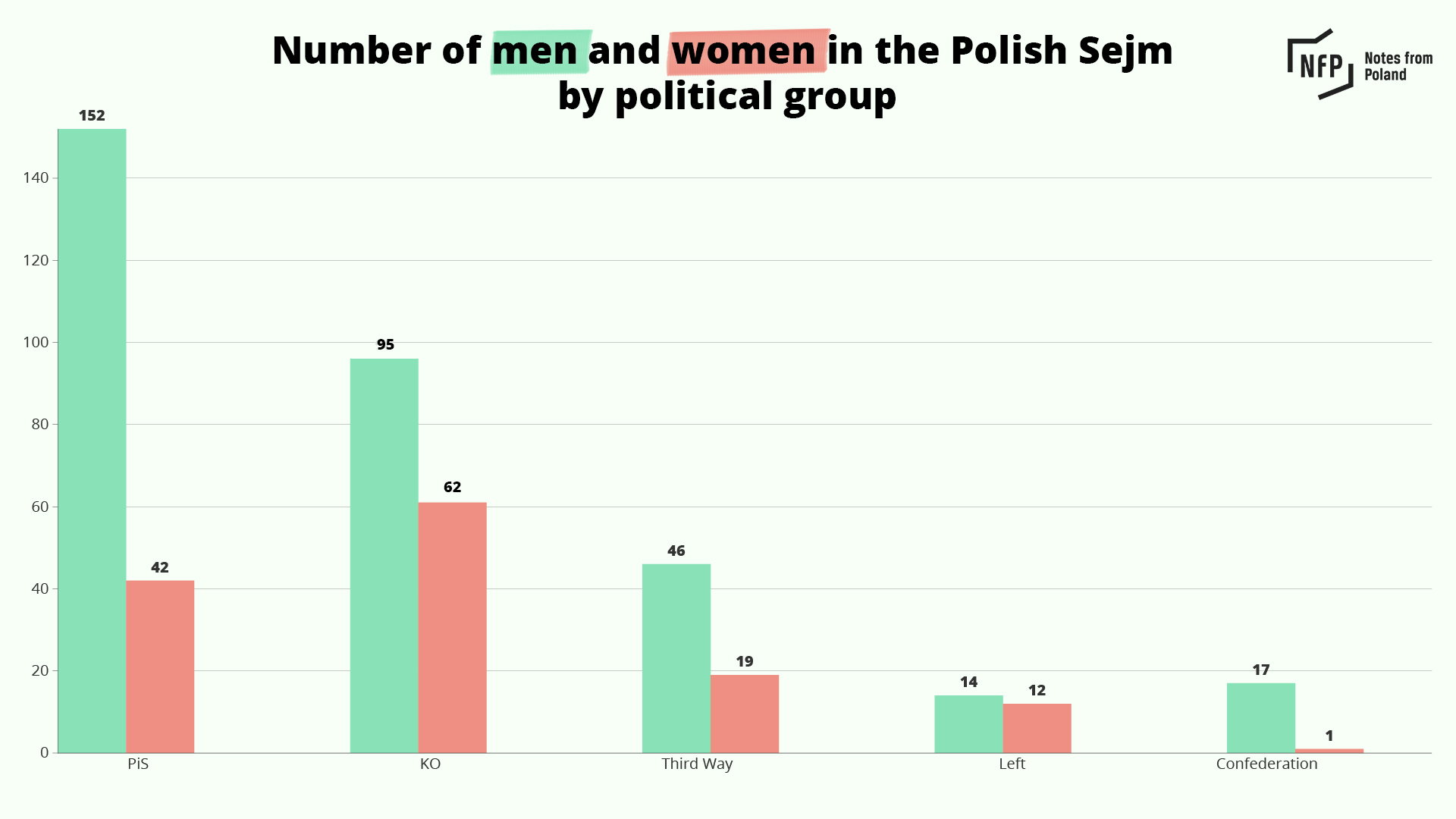

However, that figure is still well below the proportion of candidates at the elections who were female, 44%, suggesting that something is amiss. Tusk’s own Civic Coalition (KO) group gives an indication of where part of the problem lies.

Ahead of the elections, Tusk declared women’s rights the “number one issue” in Poland and pledged that there would be gender parity on KO’s electoral lists.

That target was more or less achieved, with 48% of KO’s candidates for the Sejm, the more powerful lower house of parliament, being women. However, among the KO MPs eventually elected, only 39% were female.

This, say some experts, is because female candidates (for all parties) are often given less promotion and support during the campaign than their male counterparts.

“I think that many women were put at the head of electoral lists for the sake of a party’s image, but they did not receive the same PR, financial or media expenditure as other candidates,” Olga Legosz of the SPS Foundation, which organised a campaign encouraging female turnout, told the Gazeta Wyborcza newspaper.

Women also often struggled to find a place near the top of electoral lists, where candidates are more likely to be elected.

For example, among the Sejm candidates for one of Tusk’s coalition partners, Third Way (Trzecia Droga), 42% were women. However, women only made up 20% of those who were given the coveted number one spot on its electoral lists.

These imbalances are reflected even more strongly among the most senior positions within parties. The leader of every group that stood in the elections was male. When KO, Third Way and The Left signed a coalition agreement to form the new government, all five of the signatories were men.

The opposition groups likely to form the next government have signed a coalition agreement

They pledged to:

– restore rule of law

– annul the near-total abortion ban

– depoliticise public media

– prosecute anti-LGBT hate speech

– separate church and state https://t.co/lwQvGGok8s— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) November 10, 2023

“You have a coalition of five men”, says Agnieszka Golec de Zavala from Goldsmiths University in London, who specialises in social and political psychology.

Record number of women in government

Recent months have also seen record numbers of women appointed to senior government positions, but even this has been tinged with suspicions of tokenism.

Last November, after PiS had lost its parliamentary majority but emerged as the biggest party in elections, it was given the first shot at forming a new government.

When PiS Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki named that cabinet, half of its members were female and women were at the head of 10 out of 26 ministries.

Those were record figures that in other circumstances would have been welcomed. But, given that Morawiecki’s administration was doomed to failure (it would inevitably lose a vote of confidence in parliament after two weeks) many saw his move as a meaningless gesture, especially as during his years heading “proper” governments between 2017 and 2023, very few women served in his cabinets (for long periods only one).

Poland's new government has four times more men called Michał (4) than it has women (1) pic.twitter.com/08DxOTTAVZ

— Daniel Tilles (@danieltilles1) October 6, 2020

“Women were consciously made the main force in a powerless government, which ultimately indicates a marketing action rather than an attempt to set standards of representation in Polish politics”, says Agnieszka Turska-Kawa, a political scientist and sociologist from the University of Silesia in Katowice.

After the demise of Morawiecki’s temporary administration, Tusk’s new cabinet, appointed in July, did contain a record number of women for a permanent Polish government, with nine female ministers. But, notes Turska-Kawa, the positions they were given were of “rather marginal importance”.

The traditional “big” ministries – defence, justice, finance, interior, the foreign office – all went to men. Women were mainly appointed to ministries that in the past have also often had female heads: schools, health, environment, family and social policy.

Some women were given newly created ministerial roles that do not actually have ministries attached to them: Katarzyna Kotula as equality minister, Agnieszka Buczyńska as civil society minister and Marzena Okła-Drewnowicz as senior affairs minister.

This is Poland's new government.

You can read my profiles of all the ministers and an outline of the challenges they each face here: https://t.co/FyWp03M1tO pic.twitter.com/5fsjpz8nRX

— Daniel Tilles (@danieltilles1) December 13, 2023

“We can discuss more substantial change when we start having more women leading the so-called power ministries”, says Katarzyna Grzybowska-Walecka, a political scientist at Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw, adding that “men are seen as more prestigious in foreign and domestic affairs”.

The women who are now in Poland’s government have been vocal advocates of progressive causes, but their presence does not mean such policies will be pursued, notes Simona Guerra, a senior lecturer in comparative politics at the University of Surrey.

Those “who can advocate for women’s and LGBT rights…sit in a coalition government, where more conservative elements can still constrain a more progressive social agenda”, she says.

For example, while KO and The Left want to introduce abortion on demand and same-sex civil partnerships, they have faced resistance from the Third Way and neither policy – both of which were among the 100 changes Tusk promised to introduce within his first 100 days in office – have progressed very far.

PM @donaldtusk's political group has submitted a bill to introduce abortion on demand

That would undo the near-total ban introduced under PiS and create a more liberal law than before

But Tusk admits he may not have enough support from coalition partners https://t.co/I3mIZee8RE

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) January 25, 2024

This risks leaving many opposition voters, especially women and the young, deeply disillusioned.

One of the key factors in PiS losing its majority and the rise of Tusk’s coalition was anger over the restriction of reproductive rights under the PiS government, especially the introduction in 2020-21 of a near-total ban on abortion, which prompted Poland’s largest protests since the fall of communism.

“There was a tipping point in Poland, I believe, during COVID when the PiS government overstepped”, says Patrice McMahon, a professor of political science at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, who argues that “young, female voters were the key to defeating populists in Poland’s election”.

“For women, this was their opportunity to push back and to say no, we don’t like your direction and policies and we can and will do something”, she adds.

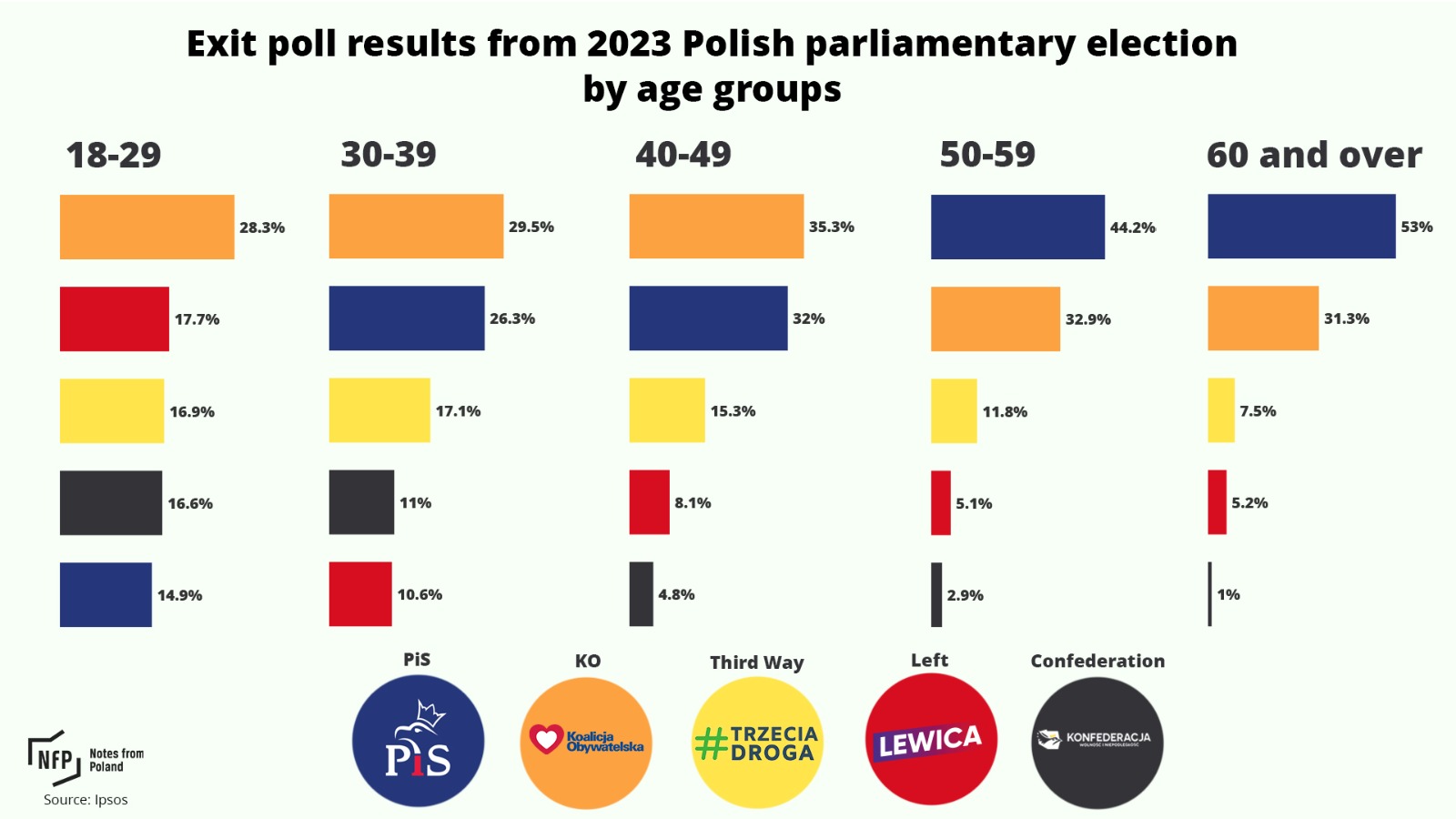

Exit polls from October’s vote show that 56% of women voted for the three groups in Tusk’s coalition compared to 50% of men.

There was record turnout of 69% among the youngest voters (aged 18-29), which was higher than the 67% among those aged 60+. Almost two thirds (63%) of the youngest cohort voted for Tusk’s coalition; among the oldest, only 44% did.

“The success of women is also due to the fact that younger women adopted different strategies and tactics, making this a movement about women everywhere – not just feminist elites in cities and at universities”, says McMahon.

But the early indications from the new government show that “they did not manage to tap into and use this genuine, a grassroots, bottom-up movement”, argues Golec de Zavala of Goldsmiths University.

“Women won this victory, but the promises that were at the forefront have not yet been fulfilled,” says Jana Shostak, an activist who stood as a candidate in the elections for The Left.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Ministerstwo Rodziny, Pracy i Polityki Społecznej/Flickr (under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)