By Daniel Tilles

The 15 October parliamentary elections are set to usher in a new government formed by opposition parties, ending the eight-year rule of Law and Justice (PiS).

However, the process of forming that new administration could take weeks. Even once in place, the government will be a broad and diverse coalition that will face challenges in tackling a number of issues – including the rule of law and abortion – while also having to deal with a potentially hostile president and his power of veto.

Below, we look at how the next few months may unfold.

So the opposition won the elections, right?

Yes and no.

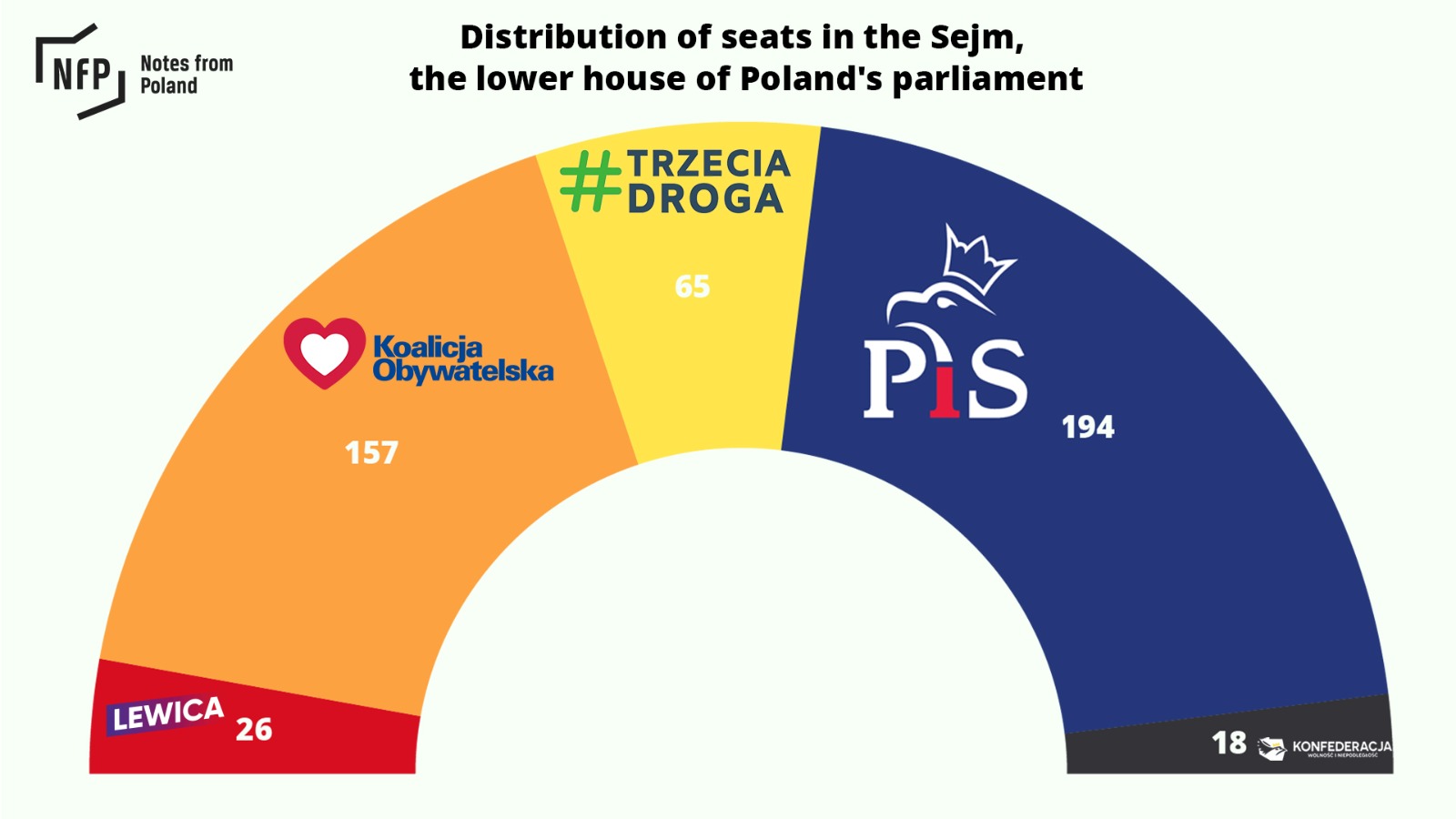

Together, the three mainstream opposition groups – the centrist Civic Coalition (KO), centre-right Third Way (Trzecia Droga) and The Left (Lewica) – have won a comfortable majority of 248 seats in the 460-seat Sejm, the more powerful lower house of parliament where any potential government must win a vote of confidence.

But the formal winner of the election – in the sense of being the single group with the most votes – was the ruling national-conservative PiS party, which won 194 seats, ahead of KO on 157 in second place.

But PiS can’t form a government, can they?

Almost certainly not. Every other party has ruled out joining a coalition with them.

In the days after the elections, some PiS figures floated the idea of holding talks with the Polish People’s Party (PSL) a moderately conservative agrarian group that makes up part of the Third Way. But PSL has made clear it has no interest in working with PiS and wants to be part of a new coalition government formed by the opposition.

Another potential partner for PiS could have been the far-right Confederation (Konfederacja), but it performed below expectations in the elections, winning only 18 seats. That would not be enough to give PiS a majority. In any case, Confederation has also rejected the idea of working with PiS.

Another possibility for PiS if it had been close to a majority would have been to try to tempt individual MPs from other parties to defect. However, they are currently 37 seats short of a majority, making that task impossible.

Despite exit polls indicating that the opposition now has a majority, the ruling PiS party has insisted it will try to form a coalition to remain in power.

But PSL, a party cited as a potential partner by a PiS figure, has unambiguously ruled out the idea https://t.co/7fQ2N9pfqo

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 16, 2023

So the opposition can now form a government?

Eventually, but not yet.

Under the Polish constitution, it is the president, Andrzej Duda, who after elections names a candidate to be prime minister. That figure then forms a cabinet, which is put to a vote of confidence in the Sejm.

By tradition, the president gives the largest party, in this case PiS, the first shot at forming a government. Duda is also a former member of PiS and has generally been its ally over the last eight years.

On Tuesday and Wednesday this week, he will hold talks with all parliamentary groups, after which he will nominate a prime minister, who could be from PiS or could be an opposition figure (mostly likely Donald Tusk). However, in theory Duda can name anyone he wants.

President Duda has announced a schedule for meeting with all parliamentary groups next week about forming a new government:.

Tuesday

12:00 – PiS

14:00 – KOWednesday

11:00 – Third Way

13:00 – The Left

15:00 – Confederation https://t.co/ndCPNeD50g— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 20, 2023

But why would he nominate a PiS prime minister if they can’t form a parliamentary majority?

There are various theories (and conspiracy theories) about this.

Some have suggested PiS wants more time in power to make life difficult for an eventual opposition government – for example, by not leaving them enough time to submit a budget before the deadline, which would allow the president to dissolve parliament.

Others claim that they want to give the Supreme Court time to potentially annul the results of the election due to some claimed irregularity. As part of its overhaul of the judiciary, PiS gave the authority to approve or annul election results to a newly created chamber of the court that is stuffed with its own nominees.

President Duda to give PiS first shot at forming government, say media reports. Comments from a PiS minister imply they may indeed take full allowable time, even with no plausible path to majority, delaying into December, as I have suggested before. If so, what is their plan? 1/ https://t.co/QC5iBZXkVT

— Stanley Bill (@StanleySBill) October 18, 2023

However, either of those two options would involve calling new elections, with no prospect of PiS doing any better (and probably more chance of it doing worse if it had sought so cynically to bring down an opposition government).

There are also those who say PiS wants to delay the arrival of an opposition government to give it more time to remove traces of any of its wrongdoing during its period in office.

But all such theories are speculation. And it remains possible that Duda will pick an opposition figure as prime minister, which would then allow the opposition to finalise forming a government in November.

And if the president doesn’t pick an opposition prime minister?

Then PiS will have around a month to form a government and put it to a vote of confidence. Once it loses that vote, the Sejm can then nominate its own candidate for prime minister and hold a vote on their proposed government.

In that latter case, an opposition coalition would not be able to take power until sometime in December.

What form would that opposition coalition would take?

KO, Third Way and The Left have long made clear that they intended to form a government together. The election results have confirmed that KO, as expected, will be the dominant force in any such government.

But they also produced an unexpectedly strong result for Third Way and an unexpectedly poor one for The Left. That shifts the balance of a future government in a more conservative direction.

Equally, however, KO and Third Way alone do not have a parliamentary majority, giving The Left some bargaining power.

Poland’s main opposition parties from centre-right to left have finalised an agreement not to stand candidates against one another in October’s Senate election.

A similar pact in 2019 helped the opposition win control of the chamber from the ruling party https://t.co/h6FOydtKKx

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) August 17, 2023

So would such a government be unstable?

It would certainly be a diverse and unusual mix.

Although the opposition stood as three main blocs in the elections, each of those blocs is made up of various parties and other groups, meaning a coalition between them all would comprise around a dozen entities.

Moreover, they encompass a wide range of ideological positions, from the socially liberal, economically leftist Together (Razem) party, which is part of The Left, to socially conservative and free-market elements contained within Third Way.

While those groups were united by their desire to oust PiS, the realities of governing together over the next four years are likely to prove much harder.

The Left has proposed policies to improve women's safety, including abortion on demand, changing the legal definition of rape and paid menstrual leave.

It also wants to end the conscience clause that allows doctors to refuse abortions on religious grounds https://t.co/MzUGFnfHdl

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) June 16, 2023

On the other hand, any such coalition would be anchored around KO, which would hold two thirds of its seats. And KO itself is dominated by Tusk’s Civic Platform party. That should provide some stability.

Moreover, since 1989 every government has to a greater or lesser extent been a coalition, meaning that there is a strong tradition of parties working together in office.

Above all, however, all elements of the coalition would know that they have little choice but to work together, given that the alternative – another round of elections – could be worse than compromise.

However, if at some stage polls show a change – for example, that KO could achieve a majority alone or with just one coalition partner – that calculus might shift and early elections could become more tempting, though would still represent a major risk.

But do these various groups have much in common?

In some areas, yes; in many others, not really.

They agree on the need to undo the PiS government’s overhaul of the judiciary and media, as well as to improve relations with European Union, including unlocking funds frozen over rule-of-law concerns.

All of Poland's main centrist and left-wing opposition parties – as well as a number of civil society groups – have jointly signed an agreement on rolling back the government's judicial policies and ending the "devastating conflict" with the EU https://t.co/1R3oLOQabI

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 7, 2021

But there are areas of difference, often big ones, on socio-economic policies – such as benefits, housing, and taxation – and what Poles call “worldview” issues, such as abortion and LGBT rights.

So the areas they agree on – such as restoring the rule of law – should be easy to resolve?

Not necessarily.

Even if the parties agree on what should be done, implementing those changes will be extremely difficult, especially when it comes to the judicial system.

Eight years of PiS rule has radically transformed the judiciary and undoing those changes in a manner that itself avoids violating the rule of law will be hard. Moreover, it will be extremely disruptive.

For example, PiS reconstituted the National Council of the Judiciary (KRS), the body responsible for nominating judges. Those reforms have been found by Polish and European courts to have been unlawful, and therefore the judges appointed by the reformed KRS to be illegitimate. Some “old” judges appointed before the reforms have refused to work with their “new” counterparts.

Thirty judges on Poland's Supreme Court – almost a third of those working at the institution – have declared they will not adjudicate alongside colleagues appointed after the government's judicial overhaul, which they say rendered such nominations invalid https://t.co/jsFW62gWih

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 17, 2022

But since its overhaul by PiS, the KRS has nominated over 2,000 judges. Just last week, President Duda swore in a further 72. To simply remove all such judges from their positions would be extremely problematic. It would also bring into question the thousands of rulings they have issued, potentially creating legal chaos.

And that is only one example relating to one institution among the many overhauled by PiS, which include the Constitutional Tribunal (TK), Supreme Court, common courts, prosecutorial service and public media, among others.

So does that mean Poland won’t be getting its frozen EU funds anytime soon?

Probably not quickly. Anonymous European Commission sources told Polish broadcaster RMF last week that they need to see concrete action on the rule of law from a new government, not just declarations about what it intends to do.

However, the EU does not expect or require every aspect of PiS’s judicial overhaul to be undone before it releases the funds. It has already agreed a series of milestones with the PiS government in order to unfreeze the money, most of which have actually been met already.

Should the new government implement measures to address Brussel’s concern over the independence of judges, especially in relation to the disciplinary system introduced by PiS, that could allow funds to begin to flow next year.

Donald Tusk will travel to Brussels for talks on unblocking EU funds that have been frozen over rule-of-law concerns under the current government.

Tusk hopes to lead a new government after Sunday's elections gave the opposition a combined majority https://t.co/jtHv3hBsZj

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 20, 2023

Will the new government end the near-total ban on abortion introduced under PiS?

It will certainly try to do so. However, the parties that make up the coalition differ on what kind of abortion law should replace it and, even if they can agree on one, it could face opposition from the TK and President Duda.

KO, Third Way and The Left have all made clear they want to end the near-total ban introduced in January 2021 under a TK ruling. However, whereas the Third Way generally favours returning to the abortion law that existed before the ruling – which is more liberal than now but was still one of the strictest in Europe – KO and The Left want to go further, introducing some form of abortion on demand.

Third Way has argued that a referendum should be held to let Poles choose what kind of abortion law they want. But The Left is strongly opposed to that idea, saying that abortion is a basic right that should not be put to a public vote.

Poland's near-total ban on abortion is opposed by most of the public, according to polls, and two opposition parties have called for a referendum to change the law

We look at whether and how such a referendum could be called, and what the outcome might be https://t.co/sQWJUAiOkn

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) April 3, 2023

Since the elections, politicians from PSL and The Left have clashed over if and how the issue of abortion should be included in any coalition agreement.

Even if some kind of compromise is reached and new abortion rules are introduced, they could be challenged at the TK, which under PiS has already ruled most forms of abortion unconstitutional. Moreover, any legislative path to changing the abortion law could be vetoed by Duda.

Is it possible that Duda will veto everything the new government tries to do?

Certainly the president, whose current and final term runs until 2025, will provide a major hurdle to the new government, which does not have the two thirds majority in the Sejm to overturn presidential vetoes.

Duda shares PiS’s ideological agenda and has played a key role in pushing through their policies in areas such as judicial reform and social policy. He is unlikely to be supportive of undoing many of those measures.

Prezydent: będę bronił ustaleń i zobowiązań zrealizowanych w ostatnich latach. Nie zejdę z tej drogi#PAPInformacje https://t.co/Fqdu06fRS1

— PAP (@PAPinformacje) October 19, 2023

The president’s relations with the new opposition government are likely to depend to a significant degree on what Duda’s ambitions are after leaving office.

Should he wish to remain in domestic politics – perhaps even as a successor to the now 74-year-old Jarosław Kaczyński as the leading figure on the Polish right – then he may seek to flex his muscles and stymie the new government’s agenda.

However, if, as has often been rumoured, Duda has his eyes on a position at an international institution, then he may be more interested in cooperating with the new government to bolster his reputation among Western allies and to potentially win that government’s support in whatever role he seeks after leaving office.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Maciek Jazwiecki / Agencja Wyborcza.pl

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.