By Alicja Ptak with images by Marcin Cybula

After Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, Poland became the primary destination for those fleeing the conflict, with millions crossing its border.

Days-long queues started forming at border crossings. Temporary reception centres were established in major transit cities, such as Przemyśl and Rzeszów, but also in large municipalities far from the border that began receiving hundreds of thousands of arrivals, including Warsaw and Kraków.

Around 77% of Poles were involved in helping refugees from Ukraine in the early months of the war, for which purpose they spent an estimated €2 billion out of their own pockets. Poland, previously an EU outsider on asylum and migration policy, was widely praised for its response to the crisis.

However, with the influx of so many people, concerns were raised about social conflicts and other difficulties that could arise as a result. Yet so far, almost a year after the break out of the conflict, the integration of Ukrainian refugees into Polish society appears to be proceeding without major problems, even though they still face challenges.

To find out what the last year has been like for the refugees themselves, I went back to talk to some of the Ukrainians I had previously interviewed after their arrival in Poland. Below you can read the stories of three of them: a mother, a wounded soldier and a high-school student.

The Mother

The Ukrainian refugees in Poland are predominantly women and children, who together make up over 90% of arrivals.

Liudmyla Kiriachok and her sons Ruslan (left) and Ivan (right) looking at pictures on the phone in the kitchen of their Polish apartment.

Liudmyla Kiriachok is a 35-year-old mother of three who had never been to Poland before the war. When she arrived last March, she was among the 95% of Ukrainian refugees that did not have a working knowledge of the Polish language.

She spoke to Notes from Poland in October about her experience of learning Polish. As has been the case with many Ukrainian refugees, the language barrier limited her career prospects. But, almost a year after arriving in Poland, she can now communicate in Polish freely.

Liudmyla Kiriachok at her husband’s family’s stationery store where she helps out.

“I think I’ve become braver,” says Liudmyla, as she drives through the narrow streets of Gniewkowo, a medieval town in central Poland.

“In Ukraine, I didn’t want to drive a car. Here I had no choice,” she explained. “I couldn’t afford to just sit back.”

Over the past year, Liudmyla has worked at a factory of processed vegetable producer Bonduelle as a coordinator for foreign workers and labour broker, jobs for which – like many Ukrainian refugees entering the Polish labour market – she is overqualified.

Liudmyla stands in front of the Boduelle processed vegetable factory in Gniewkowo, near Toruń, central Poland, where she got her first job after arriving in Poland.

She misses her previous job as a marketing manager. “I was a little like Emily in Paris,” she says, lighting up. Recently, missing the creative rush, she took up photography.

Her children have settled well into life in Poland. The youngest, 3-year-old Alisa, a little ball of energy, even asked her mother if she was Polish now. “No, you’re Ukrainian, my dear,” Liudmyla chuckled.

Liudmyla picks up her daughter, Alisa, from preschool.

Her sons, 7-year-old Ivan and 11-year-old Ruslan, attend a Polish primary school. They have integrated well, in fact perhaps a little too well: Liudmyla says Ruslan no longer wants to go for walks with his Polish girl neighbours because “they only want to kiss” him.

At night before going to bed, the four of them read together. Ivan syllabifies out loud from his Polish homework, while Ruslan, who already speaks impeccable Polish, comes to his aid whenever a word gives his little brother trouble.

Liudmyla and her children read Polish children’s book.

Liudmyla has also reconnected with a part of her husband’s distant family, who decades ago came to Poland. They have been supporting her and her children since their arrival. Her husband’s cousin’s wife, a Pole, says – tearing up – that she cannot now imagine a life without Liudmyla and her kids.

When asked whether her life is better or worse after a year in Poland, Liudmyla says “Definitely better.”

“But you know…it’s silly, I miss my little cups and my little napkins that I left at home.”

“It feels that our lives were stolen from us and we live in some kind of limbo. I am not even sure whether I should buy new cups.”

The soldier

Since the beginning of the war, 318,790 Ukrainian citizens have been treated in Polish hospitals, including 148 Ukrainian soldiers, the health ministry told Notes from Poland. Despite Poland’s efforts to help wounded soldiers, they still face everyday limitations in the availability of inclusive infrastructure.

Vlad, a veteran of the war in Ukraine, sits in the kitchen of his temporary home in Kraków.

When Vlad, a 30-year-old Ukrainian soldier (who could not give his surname for security reasons), is asked how he imagined last year would look, he smirks

“Well, I thought I would have both legs,” he says, leaning on his right leg, which has been amputated from the knee down.

One of the three cats that Vlad’s wife Olha took with her when she fled Kharkiv, early last March.

At the start of last year, Vlad and his wife, Olha Kalenichenko, had bought tickets to come to Kraków for a week-long holiday in April. While they never went on that trip due to the outbreak of war, the couple have still ended up in Kraków, where Vlad is currently in the seventh month of receiving treatment for the injuries he sustained.

While serving as a scout in the Aidar Battalion, the car he was in ran over an anti-tank mine. While he and the driver survived, Vlad lost his leg and also suffered injuries to his spleen and one of his eyes, in which he lost vision.

Vlad shows a photo of the car he was driving in when an anti-tank mine exploded. His blood can be seen on the airbag on the passenger side, where Vlad was sitting.

He came to Poland hoping to find a specialist who could restore his sight. This has not yet been successful, but he has not given up hope. In fact, once he gets better, he would like to return to the army to train young soldiers in “how not to die”.

He plans to be what he calls a “Ukrainian phoenix”, a wounded soldier returning to fight after – like the mythical bird – being reborn from ashes.

“It’s bad news for the Russians. Many of the most experienced soldiers were wounded in the spring, maybe in the summer,” he said. “And they’ve almost recovered and they’re coming back in large numbers.”

A Motanka, a traditional Slavic amulet of good fortune. Vlad says that when he had the doll, made from tied strands of yarn, by his side, he never received an injury. “It still smells of war,” he said.

Olha, a former war correspondent, says that the past year since the beginning of the full-scale invasion has not influenced their outlook on life, as both of the couple, originally from the Kharkiv region, were familiar with the war.

“We’ve been witnessing the war first-hand since 2014,” she says.

Vlad and Olha watch TV.

She adds, however, that the experience of living abroad – “in Europe”, as Ukrainians call the European Union – has boosted her pride in her country.

“We have noticed that our country, in some aspects, is much more developed, more comfortable than the European Union,” she says, giving Ukraine’s high level of digitalisation as an example. “Now everyone I know is asking themselves ‘why is it so difficult here?’”

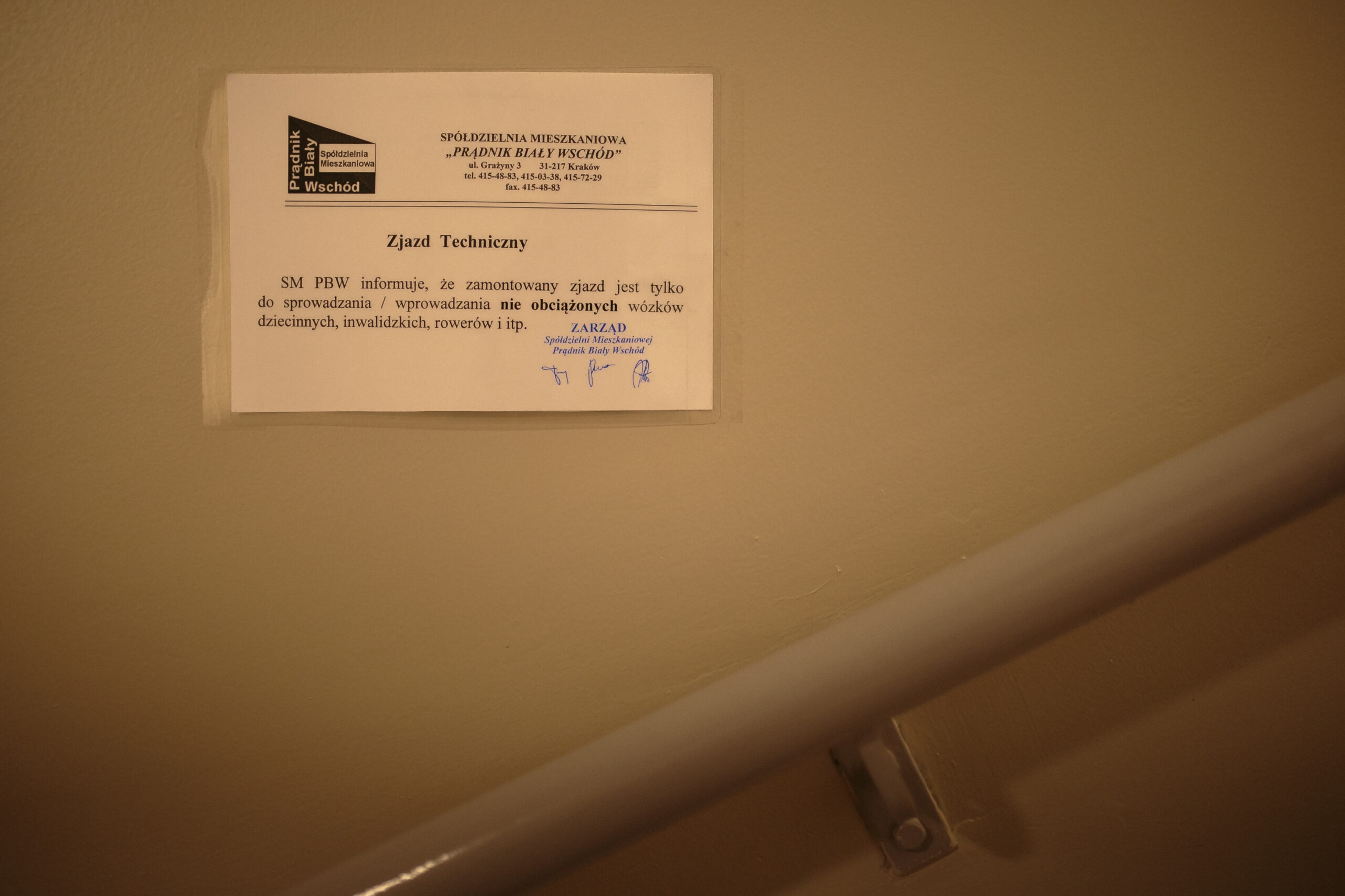

Vlad and Olha in front of a makeshift wheelchair ramp in their apartment building in Kraków.

She was particularly frustrated with how difficult it was for her to ask the cooperative that manages the block of flats where they live to install a wheelchair ramp so that Vlad could get outside more easily.

After numerous inquiries, and even an offer from the couple to pay for it, the cooperative installed the ramp. But immediately a card was hung on the staircase warning residents to use it only for empty wheelchairs.

A notice from the housing cooperative informing that the ramp can only be used for empty wheelchairs, prams and bicycles.

“I don’t know what their thinking was,” she says. Vlad still cannot stand up on his own, as his second leg has not healed from the fracture he suffered last year. Olha points out that lifting her husband is not an option.

“He weighs a hundred kilos!” she laughs.

The teenager

While many of the Ukrainian refugee children who have come to Poland have continued their education online, around 190,000 attend Polish schools or preschools, government data show.

Viktoria Cherevulia, 14, talked to Notes from Poland in May last year, ahead of the Polish elementary school graduation exams which she, and around 6,150 other Ukrainian refugee eight-graders, had to write in Polish, despite starting to learn the language only three months earlier.

She passed with flying colours, despite having had little time to prepare. Viktoria was, however, an outliner. Her Ukrainian peers received an average Polish language exam score of 22% (compared to 60% in the case of Polish pupils).

Thanks to her strong exam results, Viktoria was able to enrol in one of the top high schools in Kraków. She is the only Ukrainian among the freshmen.

Viktoria’s dog, Masa, sits on her math homework.

Viktoria’s mother, Elena, has noticed that over the past year her daughter has grown up much faster than she should have, as turbulent events and forced life changes coincided with probably the most pivotal period in a person’s life, adolescence.

“Her priorities have changed,” says Elena. “For her last birthday, she didn’t want any presents, she just asked to go home, to our family and friends.”

Viktoria, stroking their dog, a miniature Yorkshire terrier called Masa, sleeping on her lap, agrees.

Viktoria and Elena (right) pose in their apartment in Kraków.

“Looking back over the past year, I can see how much I have changed both externally and spiritually,” she says in a calm voice, with a hint of sadness.

“Before, I used to think a lot about friends, about how to spend time with them…and now I think more about the future, even though I can’t even imagine it.”

Viktoria still feels that Polish “is not her language” and feels more comfortable speaking English. Not being able to communicate freely has also made her give up aerial gymnastics, which she practised in Ukraine.

Elena shows a photo of her lavender garden in Ukraine, the passion she misses most.

She told her mother recently that “that war takes lives both literally and figuratively”.

“People literally lose their lives in war, but in a figurative sense, war has also taken our lives, peaceful, quiet, in our home,” said Elena, quoting her daughter.

Credit for all photos: Marcin Cybula

Alicja Ptak is deputy editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland and a multimedia journalist. She has written for Clean Energy Wire and The Times, and she hosts her own podcast, The Warsaw Wire, on Poland’s economy and energy sector. She previously worked for Reuters.