By Szymon Pifczyk

More than 3.2 million people have crossed the border from Ukraine into Poland since Russia’s invasion on 24 February, according to the latest United Nations figures – one of the largest refugee waves in European history.

Last month, the Union of Polish Metropolises issued a widely cited report claiming that the population of Poland as a whole has risen 8% (by almost 3.2 million people) this year due to the refugee influx, and as much as 50% in certain cities.

Refugees from Ukraine have caused large increases in the populations of Polish cities:

– Rzeszów: +53%

– Gdańsk: +34%

– Katowice: +33%

– Wrocław: +29%

– Kraków: +23%

– Lublin: +20%

– Poznań: +16%

– Szczecin: +15%

– Warsaw: +15%

– Łódź: +13%

– Bydgoszcz: +13%

– Białystok: +12% pic.twitter.com/aN8NcOK1BR— Daniel Tilles (@danieltilles1) April 25, 2022

While it is undoubtedly true that Polish people have opened their doors to hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians, the real count is likely much lower than the 3 million mark. Reports on the numbers of Ukrainian refugees currently in Poland have been couched with the caveat that “no one really knows” the true figures. What do we know about the extent of the refugee wave?

Digging deeper into border crossing data

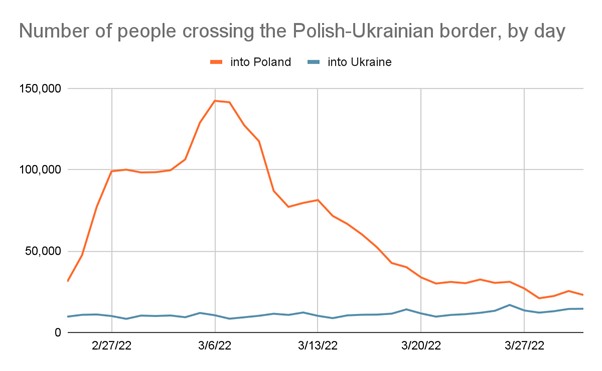

One of the most commonly cited figures – 3 million refugees – comes from the counts released by Polish border guard. This is the number of people who have crossed from Ukraine into Poland since the war began on 24 February.

But this figure lacks an important context. A humanitarian aid worker who travels between Poland and Ukraine with supplies back and forth is counted as a “refugee” every single time under this metric. Even the heads of Polish and other Western governments who visited Kyiv and then went back to Poland count toward that 3 million figure.

As the border guard notes, traffic in the other direction – between Poland and Ukraine – has also been significant – nearly 1 million in the same period.

In fact, around the Orthodox Easter holidays, on some days more people entered Ukraine than left. While reporting is delayed and the Polish government is yet to release full April data, we can see on this chart ending on 31 March that the inflow-outflow balance is trending towards zero.

Altogether, based on these data we can estimate that the actual number of Ukrainians who have left Ukraine and not returned is closer to 2 million than 3 million.

Even border crossings don’t tell the whole story

But even this figure seems inflated if we are talking about the number of refugees who are in Poland. This is because hundreds of thousands of people who crossed the Polish border and have not returned to Ukraine have continued on to further destinations.

Before the war, Poland was one of the main Ukrainian diaspora countries, amid an unprecedented wave of immigration. More than 600,000 Ukrainians were registered in its social insurance system last year, although the estimated number living in Poland was up to double this figure.

But other European countries also had sizable Ukrainian populations.

Italy and France were home to more than 200,000 Ukrainians each before the war, while Germany, Czechia and Spain also hosted more than 100,000 each. And these countries are where many of the refugees have ultimately gone, as they have family members of friends that can help them. According to the most recent data, Germany has taken in nearly 400,000, Czechia over 317,000, Bulgaria 221,000, and Italy more than 100,000.

It is difficult to estimate how many of the refugees in these countries which do not directly border Ukraine came through Poland – after all, millions of people fled through Slovakia, Moldova, Romania and Hungary, too. But many indisputably did – especially those who have ended up in Germany and Czechia, Poland’s neighbours.

So what do we know?

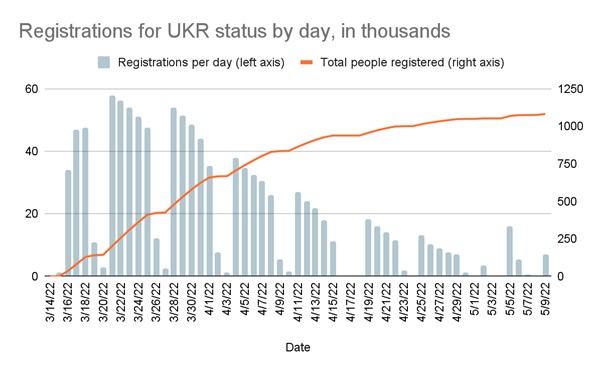

It seems that the best data source we have is the number of registrations for the special UKR status granted to refugees escaping Ukraine. This category has been created for Ukrainians being granted a Polish national identification number (PESEL) to speed up refugee integration into Polish society (allowing adults to work, children to go to Polish schools, and their parents to receive child support payments, among other things).

As of 25 April, just over 1 million people were registered with this status. As the chart below shows, after high demand and long queues early on, the number of new applicants is starting to fall. It remains quite significant, however, at around 10,000-15,000 registrations a day.

If the trend continues (and there is no other offensive in Ukraine), though, we can expect everyone who wants to register to be done by the end of May.

In terms of where in Poland refugees are located, the answer in many cases is: where their relatives and friends were already living. This means the largest cities, especially Warsaw and Wrocław, the A4 motorway corridor from the German border to the Upper Silesian metropolitan area, the “orchard belt” around Warsaw, and areas in Central and Western Poland with lots of jobs in manufacturing and logistics.

Some refugees without friends or family in Poland (or whose contacts were unable to host them) were provided shelter in hotels and B&Bs in Poland’s tourist regions, particularly the mountains and the seaside – and these areas also have high refugee populations.

Refugees with UKR status as percentage of total population:

Temporary work permits issued to foreigners (of which three quarters were Ukrainians) per 100 workers (2019):

We should also remember that some refugees have not applied for UKR status. Seeing their position as purely transitory (either because they expect to return to Ukraine soon, or move elsewhere), they did not see the point in joining queues to receive this status. Obviously, this figure is again hard to estimate.

The impact on Polish demographics

To quote Dickens: “it was the best of times, it was the worst of times”. While it sounds extremely callous and cynical, there is no doubt the refugee crisis, while challenging in the short term, can be extremely beneficial to Poland in the long term.

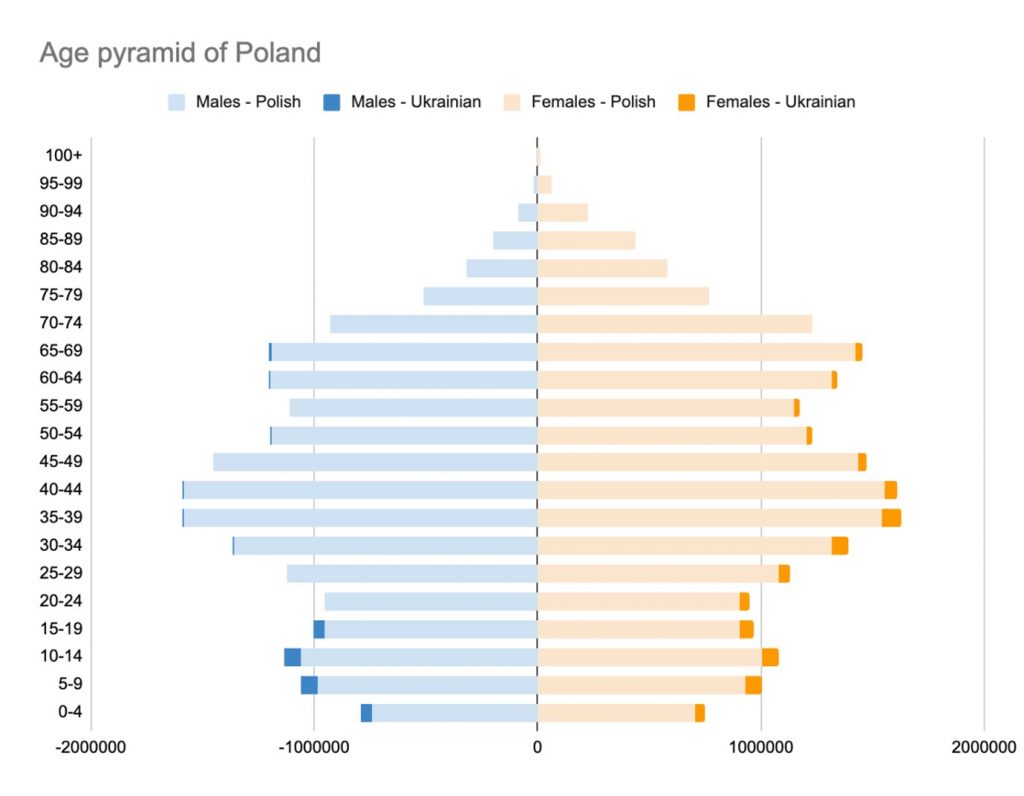

Poland, like most European countries, faces a rapidly ageing population and low fertility. Ukraine’s position is even worse on that front, and now has only worsened, since as many as 10-15% of Ukrainian children and millions of women of child-bearing age have left the country.

The effects are already being felt in Poland – of the 1 million Ukrainians with UKR status, half are children. By my rough estimate, the refugee wave has lowered the median age in Poland by almost 5 months.

For example, Poland previously had 60,000 more males in the 25-29 age group than in the 10-14 age group. The situation has now reversed – with 10,000 more boys aged 10-14 than men aged 25-29.

Note: Ukrainian refugees aged 65 and older were all added to the 65-69 age group, even if some of them were older. The official data do not report on specific age sub-groups for refugees aged 65 and older.

The population pyramid also reveals another characteristic of the refugee population – among adults, it is almost exclusively women. This has been reported anecdotally by accounts from the border and was expected as Ukrainian men of military age are prohibited to leave the country, but the data make it even clearer: men aged 18-65 comprise only 3.8% of applicants, while men over 65 make up merely 0.7%. Some 44.9% of refugees are women aged 18-65.

Whatever the precise numbers of Ukrainian refugees in Poland, it is clear that their presence will have – and is already having – a major impact in many areas of society, including employment, education and the real estate market, where the number of vacancies countrywide has dropped by two thirds since the invasion began.

As well as opportunities, the millions of new arrivals pose major challenges. So far, the Polish state and population has passed the exam of hospitality and support. It remains to be seen what the longer-term consequences will be.

Main image credit: Wojtek Radwanski/EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid (under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0). Other images belong to the author