By Natalia Parzygnat

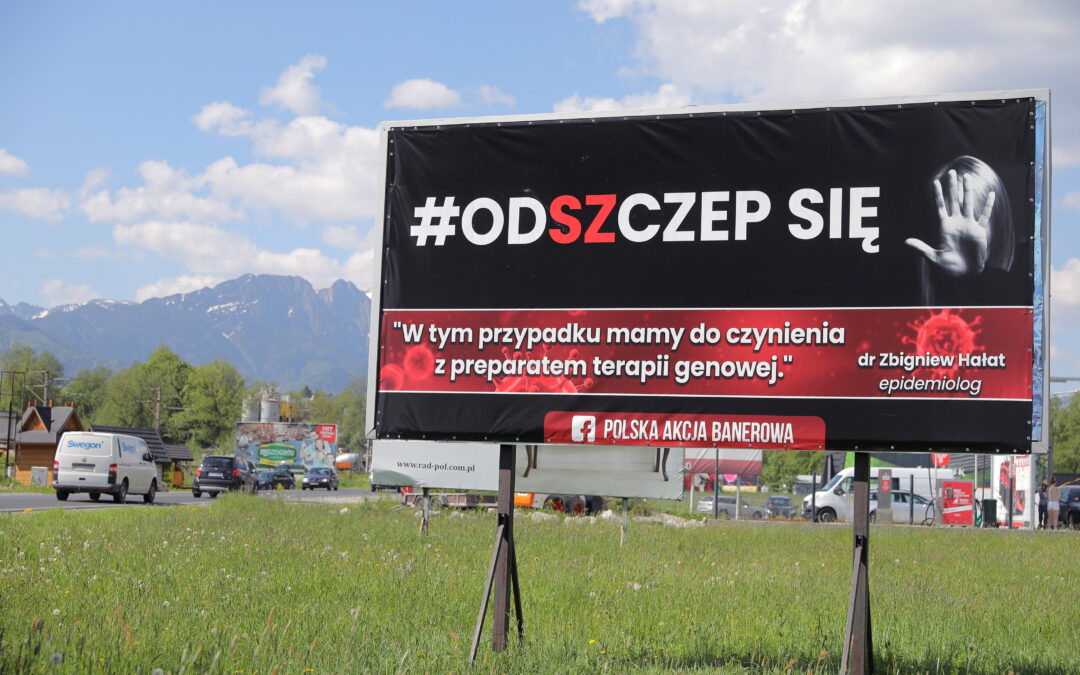

Travellers driving south on the main road from Kraków to the resort town of Zakopane this summer were welcomed by a billboard warning promoters of coronavirus vaccines to “get lost”. Vaccines are a form of “gene therapy”, it declared.

The Podhale region in Poland’s southern mountains is famous for its lively highland culture and traditions. But this year it has gained a new reputation: for having some of the country’s lowest rates of vaccination against COVID-19.

One of its municipalities, Czarny Dunajec, has the lowest proportion of fully vaccinated people (22.8%) among all of Poland’s 2,477 municipalities. Another, Biały Dunajec, is sixth from bottom, with 25.2%. Across all of Podhale, only around 35% of residents are fully vaccinated, compared to a figure of 54% for Poland as a whole.

The current surge in coronavirus infections has not made any difference. In fact, Marta Świetlik – a vaccine coordinator at the Podhale Specialist Hospital in Nowy Targ, Podhale’s biggest city – says she has observed “a dramatic decline in interest in vaccinations”. Each week between 100 and 160 patients get the jab, ten times lower than in May and June.

“Human guinea pigs”

Highlanders are “quite sceptical” of the jab, she told Notes from Poland. Indeed, “in municipalities with the lowest vaccination rates, such as Czarny Dunajec, the unvaccinated even take ‘pride’ in such a low vaccine uptake rate and manifest their superiority over vaccinated people”.

National and local authorities have run campaigns encouraging people to get the jab, but anti-vaccine messaging can often feel stronger. The “Od(sz)czep się” billboard campaign, for example, was started by a Podhale resident, Sebastian Śmietana, before spreading to other parts of the country.

It quotes a group of “Independent Polish Medics and Scientists” who express opposition to Covid vaccines (though in fact all major Polish medical and scientific bodies advocate getting jabbed). Vaccines are a “medical experiment” with unknown long-term effects being conducted on human “guinea pigs”, claims Śmietana, adding that global pharmaceutical firms “cannot be trusted with public safety”.

He also argues that the media are underreporting cases of adverse side effects, but insists that he and his group are not conspiracy theorists or anti-science.

Asked about Podhale’s low vaccination rates, Śmietana says that it makes him “proud that they can make the right choice and choose what is most precious to them: human health and life”.

“We are not afraid of illness”

Earlier this year, amid the coronavirus lockdown, the Podhale region also came to the fore when a local organisation launched a protest against Covid restrictions, which were said to be having a particularly significant impact on the area’s winter tourism economy.

The actions of the group – known as Góralskie Veto, referring to the Polish word for highlander, Góral – resulted in the government promising the region 1 billion zloty of extra support. Now Góralskie Veto’s leader, Sebastian Pitoń, known for his appearances in traditional local costume, has also become a vaccine sceptic.

“We are not afraid of illness because we already have immunity,” he told TVN. “We believe the vaccine is harmful. I’m proud to say that this is how the majority of people in Podhale think, and this is how they approach these quasi-vaccinations.”

Such rhetoric is clearly having an impact. Marek Szperlak, a local resident, says that he and his wife have refused to take the vaccine. Both have previously suffered COVID-19 and Szperlak says that his natural “immunity is definitely better than some kind of forced drug”.

Will he ever get vaccinated? “It’s hard to say,” says Szperlak. “I base my views on scientific research and I have never told anyone not to vaccinate. [If] you want to get vaccinated, take a chance, because it is a risk. Nobody ever knows what would happen.”

Szperlak notes that he is not against vaccines per se, and has received other jabs. But he feels that Covid vaccines are still a novelty and there is not enough knowledge about their effects.

“Many people are not anti-vaxxers, but demand that vaccines should not contain substances that are harmful for the body, especially for children,” he says.

Distrust in authority

Another local, 21-year-old Tomek (whose name has been changed), says his vaccine hesitancy results from the “strange behaviour of politicians”. He is opposed to policymakers forcing people to get the vaccine (though, in fact, there is no compulsory vaccination) and suggesting that they could be prevented from going to the cinema or music festivals (an idea that has been discussed but not implemented).

Tomek’s distrust of the authorities is far from unusual in Poland. An EU-wide study this year found that just 28% of Poles say that they trust the government. By contrast, in the country with the EU’s highest vaccination rate, Portugal (where 89% of people are fully vaccinated), trust in government is also extremely higher (at 58%).

Another Podhale resident to have avoided vaccinating is a nurse, Dorota (whose name has also been changed). She also expressed distrust of the government’s intentions, pointing to a lottery it launched this year to encourage people to get jabbed.

“If the government is concerned about our health and life, why do they tempt us with prizes if we get vaccinated? It’s strange,” says Dorota.

Like many in Poland, instead of vaccinating Dorota has chosen to rely on amantadine, a drug that is an unproven treatment for COVID-19 and not recommended by any country or medical authority (though clinical trials of the drug’s effectiveness are underway in Poland).

Sales of the medicine have boomed in Poland, especially in areas with lower vaccination rates. Amantadine is a “very good drug to treat influenza, as it blocks the replication of the virus”, says Dorota.

“Vaccinate for independence”

Although children aged 12 and above have been able to vaccinate since June, parents in Podhale remain reluctant to register them. The headteacher of one school, who wishes to remain anonymous, says that at the start of the year she followed health ministry guidelines to inform parents of the possibility of creating vaccination points in the school and educating pupils on the vaccine.

But, she says, not a single person came forward to get the jab.

Efforts are still being made to encourage highlanders to vaccinate. On 11 November, as Poland celebrated Independence Day, a campaign encouraged people to “vaccinate ourselves for independence”. At the Podhale Specialist Hospital, 76 people came that day to get jabbed, with 45 of them receiving a first dose.

“Considering the rate of vaccination in recent weeks, this is quite a satisfactory result, but it is still not enough,” says Świetlik, the vaccine coordinator.

What prompts those still unvaccinated to receive it so late? There are many reasons, such as pressure from family and employers to get vaccines and the high costs of testing before travelling abroad for work or holidays, Świetlik explains.

“But very few are guided by a common-sense concern for the health and safety of themselves and their loved ones,” she laments.

A radical-nationalist group entered an orphanage seeking to stop Covid vaccines for children.

Police have increased protection of vaccination points following a growing number of increasingly aggressive actions by anti-vaxxers, often with far-right links https://t.co/Bzic9tZBYz

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) August 5, 2021

“Tremendous peer pressure not to vaccinate”

Świetlik notes that there can even be “tremendous peer pressure” on, and even “persecution” against, people who vaccinate. She recalls the case of a woman who got her jab but was afraid of losing her job if her employer found out about it.

As the fourth wave of the pandemic got underway, the hospital in Nowy Targ has reopened a ward for COVID-19 patients. It admitted 30 people in just two days, only four of whom were fully vaccinated – which shows the importance of taking a booster, says the vaccine coordinator.

With infections in the region continuing to surge, the hospital has now opened a second ward offering beds for a further 40 COVID-19 patients.

Yet unvaccinated Podhalians remain reluctant to vaccinate, with their doubts fuelled by information against vaccines being spread on social media, says Świetlik.

“How do you get the highlanders to receive the vaccine? I leave that question unanswered,” she concludes. “I think we’ve exhausted most of the options.”

Main image credit: Marek Podmokly / Agencja Gazeta

Natalia Parzygnat is a contributing editorial assistant at Notes from Poland and a graduate in Multiplatform Mobile Journalism from Birmingham City University. She has previously written articles for Birmingham Eastside and featured in HuffPost UK. Natalia is a recent BJTC Award Runner Up in Social Short Video category.