By Andrew Demshuk

Ever since Georg Dehio and Alois Riegl institutionalised historic preservation at the dawn of the 20th century, conservators around the world have preached the dogma “preservation, not restoration”. Even the least impressive baroque or Renaissance-era houses should be preserved using as much original substance as possible.

But when something old burned down – even an architectural showpiece – a modern structure should take its place that spoke to the aesthetics “of our time”. The vanished landmark could be commemorated with a plaque. But it would be “inauthentic” to bring it back as a replica.

Poland had to be an exception to this rule, as Jan Zachwatowicz, the country’s general conservator, famously avowed in 1946. After Nazi Germany’s wilful decimation of Poland’s architectural heritage, Zachwatowicz became the protagonist for what has become known as the Polish School of Conservation.

Warsaw’s Old Town in 1945. Around 85% of the city’s buildings were destroyed during the Nazi German occupation.

Although Warsaw’s outlying areas took on Socialist Realist and later modernist aesthetics, the historic old town needed comprehensive reproduction “even if it is not authentic”. At a 1963 gathering of preservationists in Williamsburg, Virginia, Stanisław Lorentz, the long-serving director of Warsaw’s National Museum, reaffirmed that a modernist treatment for Warsaw (which occurred in most cities across both Cold War blocs) would have meant “that the individuality of the town, its character, and its own historical appearance would be completely obliterated”.

To sustain the “human need to feel the continuity of our general history”, Polish architects and planners had restored cities across Poland’s radically reshaped post-war borders on the model of Warsaw’s old town so that “not only the young people, but even the elders do not realise in their everyday life that this town, which appears old, is to a great extent new. And they do not feel it to be an artificial creation”.

Perhaps the most obvious vindication of the Polish School of Conservation came in 1980, when Warsaw’s old town was put on the UNESCO list of world heritage sites as “an outstanding example of a near total reconstruction”. Out of a field of jagged fragments, seven centuries of architecture were said to have been “resurrected”. By then, Warsaw was inspiring planners from East Berlin to Williamsburg on how to build liveable “old cities”.

Warsaw’s rebuilt Old Town, pictured in 2009 (Arian Zwegers/Flickr, under CC BY 2.0)

Why did the Polish School of Conservation – this exception to the rules of historic preservation – become a model for urban planning? And what is at stake when we forge “old cities” in the modern age? Before looking at the quandaries that come with historical replicas, we should explore where replicas came from and why they have become so attractive.

Parallel to the rise of modernist schools like the Bauhaus in the early 20th century, a vying approach proposed historical-looking new construction as both a reaction to the perceived monotony of modern streetscapes and an alternate means to realise the modern urge to beautify urban space through order. During and after World War One, German architects reconstructed devastated East Prussian towns with invented “local” architectural styles to make them seem historically distinctive.

With the return of Polish statehood in 1918, the Polish School of Conservation was already reconstructing battle-damaged towns like Gorlice and Kalisz in a “Jagiellonian Renaissance” style that selectively erased the heritage of each partitioning power. And long before the Nazi incursion of 1939, Zachwatowicz was trying to rebuild Warsaw’s medieval walls in place of modern tenement buildings.

By the 1970s, modern blocks and highways had generated a pervasive sense of uprootedness, a desire for what I call historyness: “a consoling, selective visual testimony of historical authenticity in place of alienating modern urban surroundings”. Across post-war Poland – and now much of the world – politicians, planners, and developers plastered old-looking façades over modern superstructures to “restore” lost identity.

Bombed and razed, the organically layered and complex premodern cities were lost forever. But we could replicate them as stage props and pretend they had not changed.

Back in Williamsburg at the 1963 conference, American scholars and planners were hungry for the historyness that Lorentz and his colleagues had achieved across Poland. Just two years before, Jane Jacobs had published The Death and Life of Great American Cities as an excoriation of modernist demolitions and monotony she felt were ravaging bygone forms of human interconnectedness.

One of her solutions – the concept of an “eye catcher” – could easily apply to replicas. Just as for Jacobs the original purpose of an “eye catcher” was irrelevant (whether it was a church, market, or war monument), so too a replica could radiate an aura of identity for communities, regardless of the actual historical object it mimicked, much less the fact that its interiors were substantially, usually even aesthetically modern.

Behind lavish façades across Warsaw’s old town, most interiors are in fact austere: 1950s apartment buildings, shops, and offices. Communist authorities naturally trumpeted their creation of modern housing for workers behind what looked like bourgeois patrician façades. And yet their ideals of “light, air, and green” for workers joined a longstanding European ideal for modernisation. Most old towns in Europe had been dark and dank poor districts before the war.

The sheer modernity of Poland’s new old towns manifested, not just in the electricity, hot water, flush toilets, and other amenities that had been absent within most original structures, but also in their external layout. When I first peered out from the tower of St Mary’s church in Gdańsk in 2002, I was astonished to take in so much green across the old town. Behind seemingly identical gingerbread house rows, lush yard spaces stretched where, before the war, a jumble of back buildings had choked out all the light and air.

Gdańsk, on Poland’s northern Baltic coast

At first glance, then, a new old town can be far more liveable than the unhygienic original one, while simultaneously allowing residents to escape the monotony of modern boxes. Small wonder that cities around the world are embracing the Polish model to liven up their boring cores with an aura of historyness. Especially as this trend accelerates, however, we should step back to address three dilemmas about replicas that critics were already debating right after the war.

First, the very prospect of building Warsaw or Gdańsk “everywhere” betrays the fact that this process of replication may perpetuate the “sameness” of modern existence. If historic-looking gingerbread façades pop up in every European city – pasted over modern interiors – city centres will look much the same anyway. Such modern manufacturing of history also homogenises how we see the past. More on that in a moment.

Second, we need to remember the longstanding critique of architects, planners, and preservationists that replicas run counter to the “authentic” preservation of existing historical structures. Whereas preservation retains historical traces, replicas invite historical falsification. If one could reconstruct Warsaw’s Royal Castle in the 1970s with a 17th-century appearance, purged of all later accretions, why not build the same castle in Gdańsk? Or Paris? Or Cleveland?

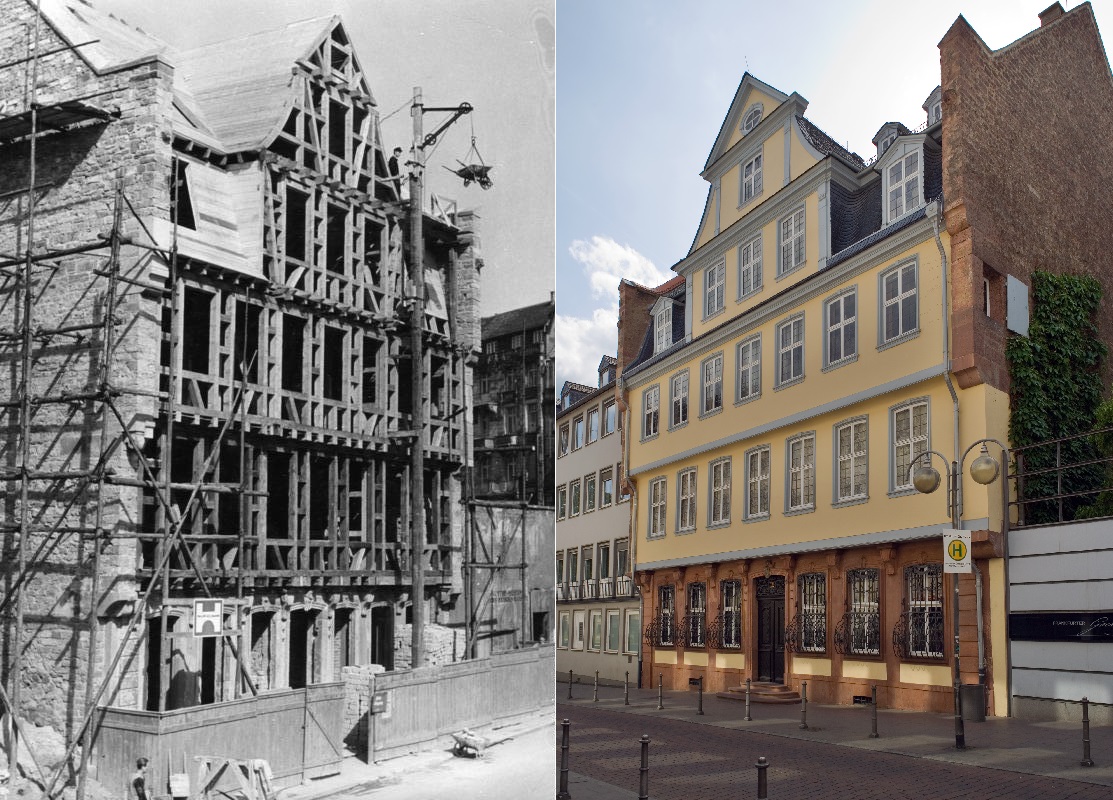

Replicas pretend that something is still there (or has ever been there). This quandary featured when diverse figures across immediate post-war Germany debated whether to forge a replica for Goethe’s decimated childhood home in Frankfurt. A replica would be a “lie” and sign of continued German “cultural decline”, an architect wrote from the Soviet-administrated zone; the only way forward was to “carry through nonetheless toward reflectiveness and truth, however painful and full of resignation such a step may be”.

Frankfurt commentator Walter Dirks famously rejected a replica as a “singular lie” that would “irrevocably falsify the spiritual inner core of this sublime city”. Inevitably, he feared, “this artificial Goethehaus will fall prey to tourists”. As much as Goethe offered a redeemable past for the German nation, Germans had to “have the courage to say goodbye”. A modern museum or plaque had to suffice on the historic site.

Yet in no small part because Goethe offered a usable past after Hitler, Frankfurt’s city council narrowly voted for a replica, and through the intervening decades Germans and visitors alike have embraced it as a seemingly self-evident shrine to a better national story. Goethe’s house portrays Germany as it should be.

Goethe House under construction in 1949 and as it appears now (Bundesarchiv/Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 3.0; Mylius/Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 3.0)

Finally, replicas have the potential to exacerbate the selectiveness of memory. As historian George Mosse remarked after Lorentz’s presentation in Williamsburg, replicas stemmed from “a didactic purpose, favouring the one past which, opposed to other pasts, the present feels worth preserving or re-creating anew”.

I could see Mosse’s point in Gdańsk. After the expulsion of the city’s German majority, Polish settlers without previous knowledge of the city came to inhabit streetscapes purged of structures and symbols associated with the German past. The heterogeneous messiness of premodern identities and interchange disappeared behind the homogenised mythology of an eternally Polish city.

It was a trend consistent across Poland’s so-called “Recovered Territories”, a swathe of former German lands Poland had acquired through the 1945 Potsdam agreement. Any inscriptions, monuments, or façades associated with Germanness disappeared, while ancient “Polish” structures arose from the ruins, sometimes as complete historical fabrications.

Preaching inside the reconstructed walls of Wrocław’s suddenly medieval-looking cathedral, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński proclaimed in 1965 that the very stones were “relics” that spoke to the structure’s “Polish soul”. In his 1963 Williamsburg address, Lorentz conflated the reconstruction of Warsaw with the nationalist reinvention of formerly German cities.

Eager to find their footing after wartime destruction and migrations, residents generally welcomed the outcome. In the 1957 questionnaire “Wrocławians talk about their city”, residents gave overwhelmingly positive appraisals of the restored old town, declaring that for them the new façades were not “pseudo” at all. The heroic Polish narrative of national redemption and resurrection effectively dovetailed with their desire to combine modern amenities with a sense of history and hominess.

By the second half of the Cold War, West and East German onlookers were allured by the liveability of Wrocław or Gdańsk. Notwithstanding the Polish national mythos, it seemed to them that Poles had reconstructed onetime German cities better than they would have. And they embraced replicas as a way to selectively recreate their own idyll of a timeless past. Polish craftsmen started arriving in both Germanies to help with preservation and replication projects.

Frankfurt was on the forefront of this turn against modernism. In the 1980s, a row of half-timbered houses appeared on its historic Römerplatz across from City Hall – their interiors cement and fire-resistant, their foundations firmly mounted atop a parking garage. Popular demand for historyness in Frankfurt persisted alongside marketing schemes to enhance the city for business and tourism.

A 1973 brutalist city office complex disappeared from the heart of Frankfurt’s old town in 2011. Under the slogan “the city lives”, a new old town opened just before the COVID-19 pandemic shut everything down: a fanciful meld of replicas and postmodern confections on the footprint of the erstwhile brutalist colossus. Complexities such as the district’s working-class, socialist, fascist, and Jewish pasts are imperceptible against the backdrop of pleasing old façades that generate whatever history people seem to want.

Frankfurt Old Town (G Da/Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 3.0)

Of course, Frankfurt’s Goethehaus had already proven that a replica could offer Germans a redeemable past after Hitler, just as Poland’s replicated old towns celebrated national resurrection after wartime martyrdom. Notwithstanding starkly differing departure points, each case selected a redeemable national past after traumatic recent history.

If Goethe’s house projected a humanist, anti-fascist Germany, however, one wonders what “didactive purpose” is served through Frankfurt’s new old town. In dealing with replicas, after all, the question is far less “which style” but rather “which past” we want to make into perceived reality in our surroundings.

Today we are experiencing a global replica craze. Berlin’s replicated city palace just opened its doors as a fraught museum. Braunschweig’s vanished palace has returned as a shopping mall façade. Replicas are all the rage again across Poland, as smaller, formerly German centres like Głogów or Elbląg seek out their own aura of historyness.

Glogów (author’s own image)

Vigilance is needed, lest we start believing in the systematised, sanitised, nationalised idyll of historyness.

Across the former German territories, Polish residents have increasingly discussed their cities’ complex and multivalent pasts – a much-needed corrective to the intentionally “cleansed” cityscapes they have inherited. One hopes for similar conversations in Frankfurt. When I chat with locals on the Römerplatz, few know about the information plaque on a replicated half-timbered house detailing its genesis in the 1980s.

The poured-cement pastiche on a parking garage is “real” to them, the backdrop for a homogenised and pleasing “history” without the painful heritage of Nazi horrors. We should use replicas as an opportunity to discuss the complexities of actual history, lest we forget that it was nationalist fantasies that unleashed so much urban destruction in the first place.

Main image credit: Gerard Stańczak/Wikimedia Commons (under CC BY 3.0)