By Paweł Bukowski and Wojtek Paczos

Poland is no longer Europe’s “green island” of growth, as it was during the 2008 financial crisis when it was the only country not to fall into recession. Yet its economy has managed to avoid the pandemic-induced troubles brewing in western Europe. However, contrary to government claims of able stewardship, it is good fortune, prioritising GDP over health, and restrictions centred more on personal than on economic freedoms that may have been what got Poland through relatively unscathed.

In 2020, Poland’s GDP contracted by “only” 3.5%, significantly less than the OECD average of 5.5%. In the UK this figure stood at a staggering 9.9%. While unemployment rates have soared across Europe, the official Polish figures have hardly budged, and are the lowest in the EU according to the latest Eurostat figures.

We should keep in mind that the Polish economy was also performing very well before the pandemic. It had been forecast to grow by 3.1% in 2020, according to the IMF’s World Economic Outlook from October 2019.

However, the Polish economy’s drop to 6.6 percentage points below the expected growth figure is still a milder slowdown than in many other countries. For instance, in the case of the Czech Republic it was 8.1 p.p. (from +2.6% to -5.5%), Hungary 8.3 p.p. (from +3.3% to -5%), the UK 11.4 p.p. (from +1.4% to -10%), and Spain almost 13 p.p. (from +1.8% to -11%).

While the Polish economy has clearly managed to navigate the pandemic relatively well thus far, the reasons for this are less clear. The country’s government has been quick to claim the success of its various anti-crisis measures.

The reality, however, is that the Polish response to the economic fallout was neither more innovative nor more generous than those of other countries. According to Eurostat, public spending rose by 9.1% of GDP in Poland between the first and third quarters of 2020, while the EU average in that period was 10.1%.

Contrary to government claims, we think that a relatively lax approach to economic lockdown and a bit of sheer luck are the main reasons for the relatively good performance of the Polish economy.

Getting lucky in the first wave

By “sheer luck” we mean all the factors that are beyond the direct control of policies but affect the transmission of the pandemic and the country’s economic fortunes nevertheless.

Poland was “lucky” in three important respects: its semi-peripheral location and its geographic as well as economic structures. As we will argue, those factors markedly affect the trade-off between the economy and public health.

Due to its semi-peripheral location, the first coronavirus case appeared in Poland relatively late, giving the government more time to prepare and implement a lockdown strategy. The first restrictions were introduced when the 7-day average of daily cases stood at just nine – rather than 674, as was the case in the UK.

Polish retail sales jumped 17.1% year-on-year and 16.5% month-on-month in March, well above expectations. Industrial output grew at its fastest rate in 15 years.

"The economy has adjusted to functioning during a pandemic," says @gmalisze https://t.co/7eYdsnjT7O

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) April 22, 2021

New research by the IMF suggests that early but tight lockdowns are most effective in containing the spread of the virus. They are also (potentially) the least harmful to the economy because, if successful, they can be lifted more quickly.

Second, Poland’s geographical structure meant that the “natural” speed of transmission in Poland was slower than in more densely populated western European countries.

In Poland, 40% of the population lives in the countryside, which greatly limits the number of daily contacts. The “lived density” of the population in Poland equals only 196 per populated square kilometre, compared to 531 in the UK.

Restrictions: when, what and how?

During the first, spring 2020 wave of the coronavirus, there was no statistically significant increase in the number of excess deaths (above the five-year average) in Poland and the economy was doing well. The policy of early and tight restrictions circumvented the painful trade-off between health and economy.

This changed dramatically during the second, autumn wave of the pandemic that reached its peak in November. The government then implemented a wait-and-see approach, introducing belated measures that ultimately proved less adequate. This can be interpreted as favouring the economy over health.

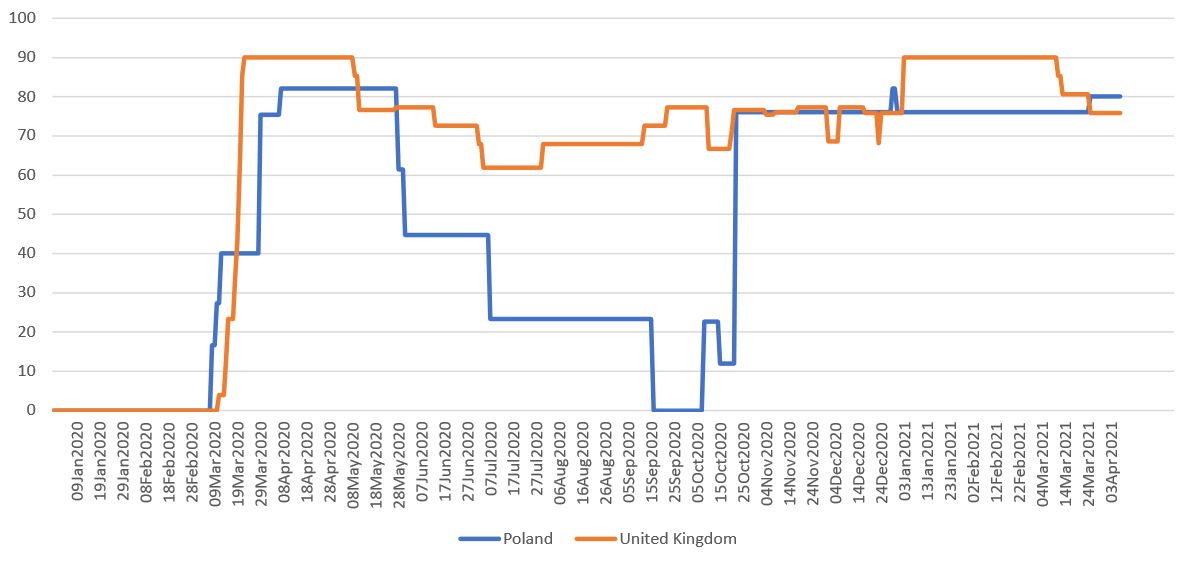

In the figure below we modify the Oxford Covid-19 stringency index to show the composite measures that are most harmful to the economy. The original index is based on nine indicators rescaled to a value from 0 to 100, where 0 is the pre-pandemic situation and 100 stands for the most stringent measures implemented in all categories. Our modification includes six categories that we believe are most harmful to the immediate economic situation.[1]

The economic severity index

Source: Own calculation based on Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker

The graph shows that the Polish restrictions were strict during the first wave and then almost non-existent in the summer. The increase in restrictions in autumn, when compared against the number of cases, is, in our opinion, much belated.[2]

By contrast, in the UK the restrictions were kept high during the summer and the increases in restrictions in the autumn were much better timed. This may have hurt the economy more, but also resulted in the much slower transmission during that second, autumn wave.

The difference, in some part, may also be explained by a different approach to restricting economic and personal freedoms in each country.

In the UK, for instance, there have been few limits on individuals: masks were never made compulsory outdoors, schools remained open for several months, and – from the authors’ own experience – quarantine enforcement has been relatively lax.

However, work-from-home was recommended for almost the entire year. During the lockdowns, Britons could only buy non-essential products online and had no access to any form of indoor services.

By contrast, in Poland masks were made compulsory even on empty streets, schools were fully opened for only six weeks, and those in quarantine were checked on regularly by police officers.

However, remote work was only strongly pushed for a few scattered weeks. For most of the past year, Poles could still go to a shopping mall or even visit a sauna.

Our intuition is that the Polish approach put less burden on the economy, while the British one is probably more effective in limiting virus transmission. This is supported by the data relating to the total death toll of the COVID-19 pandemic.

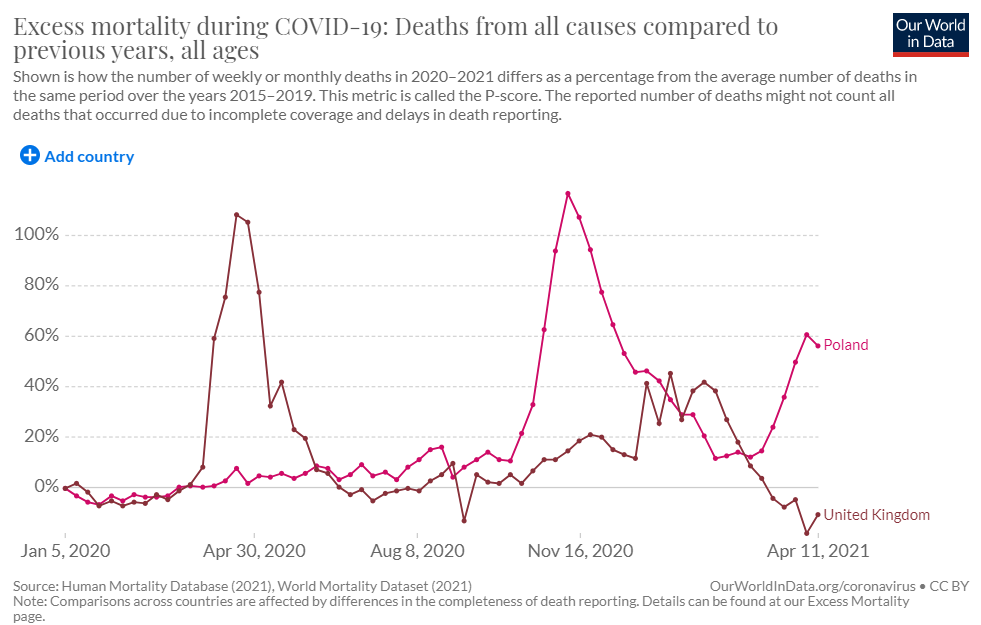

We use a measure of “excess mortality” (number of deaths above the five-year average) as these data are free from potential differences in (mis)reporting and classification. The graph below shows that, during the first wave in spring 2020, early and tight lockdown in Poland resulted in virtually no excess deaths, while in the UK delayed restrictions led to excess mortality of over 100%.

Then, however, the situation was almost reverse during the autumn second wave. In the year between March 2020 and March 2021, the UK lost almost 121,000 additional lives, while Poland lost more than 95,400. In relation to the country’s respective populations – with the UK being 80% more populous – Poland had 42% higher excess mortality per capita. Virtually all of the difference falls on the second wave.

Excess mortality in Poland and United Kingdom during Covid-19 pandemic. Source: Our World in Data.

Services suffer, manufacturing booms

Moreover, the composition of the Polish economy also makes it is more resilient to lockdown measures. In 2019, 27% of workers were employed in the sectors that were later directly affected by the lockdown (such as hospitality or tourism), compared with 34% in the UK and 37% in Spain, according to Eurostat. Since a smaller part of the economy had to hibernate, the direct effect on GDP was less negative.

But there was also a second, indirect, channel. Poland is the only big EU country that has a growing share of manufacturing in both employment and production. This kept more of the economy humming when the service services sector had to be locked down. Also, thanks to this, the country was able to benefit from the global shift in consumption from services to durable goods induced by the pandemics.

Size matters too. A big domestic market reinforces the positive effects of the business-friendly lockdown and a resilient economic makeup. Smaller countries in the region, such as Hungary or Slovakia, are more dependent on the economic situation in the rest of Europe. The larger economic fallout in Germany or the UK will thus drag down smaller economies more. Because of its size, Poland’s domestic economy could in part compensate for the loss of external demand.

Poland and the UK pursued different paths during the first and second waves of COVID-19, providing a natural experiment on how the form and timing of lockdown policies can affect economic slowdown and virus containment. Moreover, the sectoral composition of the economy and geographical distribution of the population also play crucial roles.

Although the performance of the Polish economy during the pandemic appears surprisingly robust, we do not think it was the result of a thought-through strategy. On the contrary, percentage points in GDP figures can never justify the price of almost 100,000 excess deaths. A price that, as the first wave in Poland demonstrated, was entirely avoidable.

Main image credit: Queven/Pixabay (under Pixabay License)

[1] We exclude school closures and bans on international travel and include the remaining six categories: workplace closures, cancellation of public events, restrictions on gatherings, limits on public transport, stay at home orders, and internal movement restrictions. The index is calculated as a weighted average of severity in each of the six areas. The calculation of severity includes, for example, whether the measures were implemented locally or country-wide.

It should be noted that according to a growing body of research, school closures have a strong detrimental effect on future economic growth. In fact, school closures may prove to be the most hurtful restriction to the economy in the long run. Here we exclude school closures, as we take a short-term approach and focus on the performance in 2020 only. Also, due to differences in how the economic Value Added is measured in the public sector, school closures will show up in 2020 GDP figures for the UK, but not in the figures for Poland.

[2] The trend in a number of cases pre-dates the trend in the number of excess deaths by about two to three weeks. The numbers of excess deaths are available in Figure 2.