By Paweł Wiejski

One of the Polish government’s key strategic projects, a north-south highway stretching from the Baltic sea to the Mediterranean, has erupted into an environmental dispute that could draw in the European Union.

NGOs and scientific organisations are protesting about the fact that the proposed route of the express road in eastern Poland would cut through the largest national park in the country, which is a site protected by Polish and EU law. Local authorities and the Polish government, however, point to the economic benefits of the project.

The brewing conflict has revived memories of a similar environmental clash in the same region over a decade ago, which resulted in the European Commission and Court of Justice intervening to force Poland to end construction of a planned road.

But, as public consultations continue, there is still a chance to strike a deal satisfactory to green activists, local residents and officials, while also conforming to Poland’s European commitments.

Connecting eastern member states

The project is a part of Via Carpathia, a highway linking Lithuania with Greece via Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria. For Poland, the road is more than a transit route. It will lead through the most underdeveloped regions in the eastern parts of the country, raising hopes of economic growth.

It is also a strategic priority for the government in Warsaw, which sees Via Carpathia as a way to strengthen links with other countries in Central and Eastern Europe, as it will connect several members of the Three Seas Initiative, a regional forum bringing together the EU’s eastern member states.

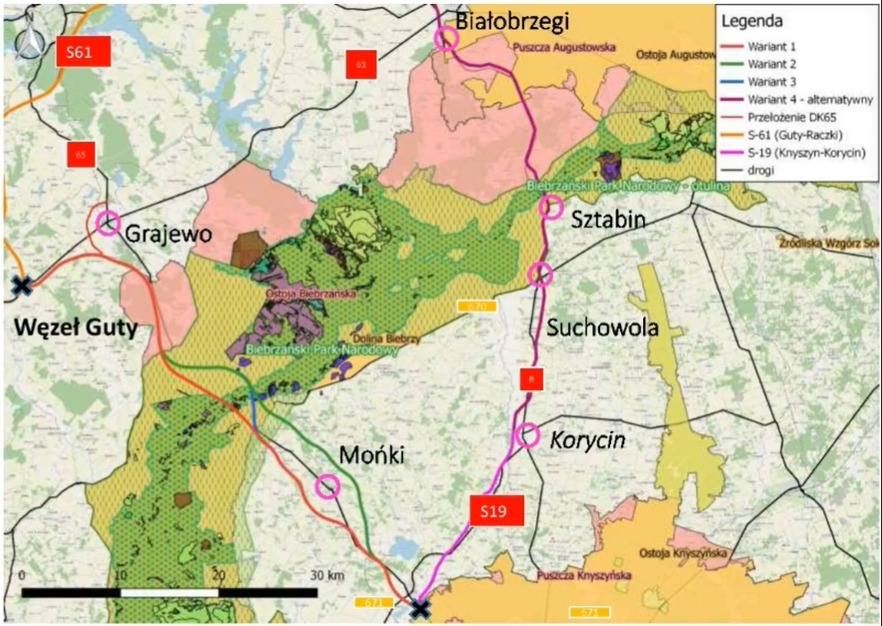

The planned route of Via Carpathia (image: GDDKiA)

The road’s most contentious fragment is meant to cut through the Biebrza national park in Podlasie Province. It is home to one of the largest wetland areas in continental Europe and a habitat for numerous species of rare and endangered animals and plants.

In spring, the marshes of Biebrza serve as a nesting site for over 200 species of migrating birds. It is also a tourist attraction, bringing over 20,000 visitors each year to one of the EU’s poorest regions.

“Scar in the landscape”

“If the road goes ahead, it means that environmental protection in Poland does not exist,” Tomasz Kłosowski told Notes from Poland. As a photographer and journalist, Kłosowski has been documenting Biebrza’s wildlife for decades.

“Biebrza is attractive for people thanks to its unique landscapes, almost untouched by civilisation. Now imagine a large, loud highway through the middle of it, which even before it is finished it will be a large construction site, which will be a scar in this landscape,” he warned.

Proposed routes of the road through Biebrza national park (image: GDDKiA)

The project is currently at an early stage. The German construction company Schuessler-Plan, along with Poland’s road agency (GDDKiA), are wrapping up a public consultation to determine the optimal course of the highway.

In the consultation process, participants could choose from four variants of the road. However, according to activist Robert Chwiałkowski from Fundacja dla Biebrzy (Foundation for Biebrza), all of the proposed variants lead through the national park and areas protected under European and national law as part of the EU’s Natura 2000 network.

He believes this is unacceptable. “A highway may lead through the Natura 2000 area only if there is no alternative solution. Our foundation has pointed to such an alternative variant,” he said.

The alternative proposed by Fundacja dla Biebrzy avoids the Biebrza national park altogether, taking a wide detour west through the cities of Zambrów and Łomża. Out of over 4,000 submissions in the public consultation process, around 90% of respondents supported this variant, mostly copy-pasting the form provided by the foundation.

The popularity of this alternative route was met with outrage from local government officials. According to Błażej Buńkowski, the head of Mońki county, most of the respondents are not local citizens, but people from around the country, who are not aware of the local circumstances.

“It is important that we are given a chance to speak in our own name. That we are not taken hostage by people who are well known for their capabilities to mobilise support, connected with environmental organisations around the country.”

What kind of development for the region?

Buńkowski and other local officials see the road project as a once-in-a-lifetime chance to develop their region economically. His district would benefit from the highway if it was built according to the original proposal by the road authority, along what currently is national road no. 65.

Shortening the commute to nearby Białystok, a large city and a regional capital, would bring housing development in Mońki and other towns along the planned highway.

“Along the express road, we could see new logistics and freight infrastructure, for example warehouses. We could better utilise the human capital of our region. Each town would benefit in its own way”, he said.

But according to environmental activists, the promises of economic development connected to the project are overstated as the express road would mostly be used by long-distance transit. It would, however, damage local tourism and agriculture.

“In some places a better road can lead to economic development,” admits Kłosowski. “But here the goal should be to develop the ‘soft’ economy: tourism, sustainable agriculture. We see these sectors growing already”.

But Buńkowski thinks it may not all be so bad. “Tourism in the Biebrza national park is highly specialised. We have people coming in early spring to see the birds’ migration,” he said, adding that large swathes of Biebrza swamps are difficult to access on foot. In his view, an express road may even make the national park more accessible.

“There is a possibility to have viewing points on the express road viaduct over Biebrza, where people could stop and appreciate the view over the park. Environmental organisations should consider this option,” he said.

The shadow of Rospuda

The conflict around Biebrza conjures up memories of some of the largest environmental protests in contemporary Poland, which erupted over 13 years ago over the Rospuda valley in the same region.

In 2007 a group of activists formed a camp in the Rospuda Valley, north of Biebrza, to block a planned ring road around the town of Augustów. Activists saw the investment as a threat to the environment. Over 150,000 people signed a petition started to stop the investment. But for local citizens, the ring road was seen not only as an economic boost, but also as a way to improve safety and reduce pollution by redirecting heavy vehicle traffic from the town centre.

In the end, the ring road was blocked by the European Court of Justice, which ordered a stop to construction work after a complaint by the European Commission arguing that the investment was endangering the Natura 2000 sites in the Rospuda Valley.

The Polish government did not fight back, and in 2009 the ring road was rerouted to avoid the Rospuda Valley altogether. The project was finished in 2014, years after the original deadline, to the dismay of Augustów’s citizens, who had to deal with heavy traffic for longer than necessary.

The current dispute could end up being “much worse than Rospuda,” says Kłosowski. “The project violates two Natura 2000 areas and a national park. It contravenes international agreements on natural preservation.”

Chwiałkowski, from Fundacja dla Biebrzy, concurs: “There is no way the European Union will agree to this. It seems that the government did not learn their lesson from Rospuda.”

Tomasz Żuchowski, acting president of the GDDKiA, says his institution is listening to all sides. “We do not want and we cannot have another Rospuda,” he said during an online public debate on the future road infrastructure in Podlasie Province last week, promising to continue consultations.

In the EU’s bad books

Sources close to the European Commission told Notes from Poland that the commission is aware of the plans to build the express road through Biebrza national park. They say that the authorities can approve the project if it has been confirmed that it does not impact the integrity of Natura 2000 sites.

If such impact cannot be excluded, the project can be approved if there is an overriding public interest, there are no alternatives, and compensation measures will be put in place to minimise the impact. “Public consultation is still ongoing. Hence, the authorities still have possibilities of ensuring the compliance of the project with the EU nature legislation,” says a source.

Via Carpathia is not the only investment in Poland that has raised eyebrows in Brussels over potential breaches of environmental laws. In March, the European Commission launched an infringement procedure in relation to Vistula Spit canal. Similarly, environmental groups have argued that the investment will damage Natura 2000 sites.

Despite these concerns, the Polish government is pushing ahead with the investment, which is scheduled to be completed in 2022 at the cost of 2 billion zloty, more than twice the original estimate.

Last week, the European Commission referred Poland to the European Court of Justice for breaches of Natura 2000 laws. According to the commission, Polish forest management plans do not ensure adequate protection of habitats and do not offer judicial remedy for the public.

The commission has been calling on Poland to review its forestry rules since 2018, but no progress has been made. A negative verdict of the ECJ may lead to financial sanctions for Poland.

Buńkowski admits that the possibility of EU intervention blocking the project of the highway is of real concern.

“Of course I’m afraid of that, but I hope that the European Commission will take into account the development that the project will bring,” he said, adding that the environmental impact of the investment will not be significant, as it will mostly replace existing roads with already heavy traffic.

In the case of Rospuda, a conflict with the EU led to years of delays and rerouting of the ring road. For Via Carpathia, time is even more of the essence. While the contentious fragment through Biebrza is at an early stage of planning, the process for the fragments north and south is much more advanced. Eventual rerouting of the highway after an EU intervention may prove complicated and costly.

Long delay may also make financing more difficult. As the EU budget shifts to support more sustainable investments, the amount of money for building polluting highways will inevitably shrink, forcing the Polish government to pay for the project out of its own pocket.

Main image credit: Jerzy Strzelecki/Wikimedia Commons (under CC BY-SA 3.0)