Poland has lifted the statute of limitations for communist crimes, many of which would have otherwise been time-barred from the start of next month.

An amendment to the law on the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN), signed by President Andrzej Duda on Friday, will now allow prosecutors to press ahead with cases relating to Poland’s decades of communist rule.

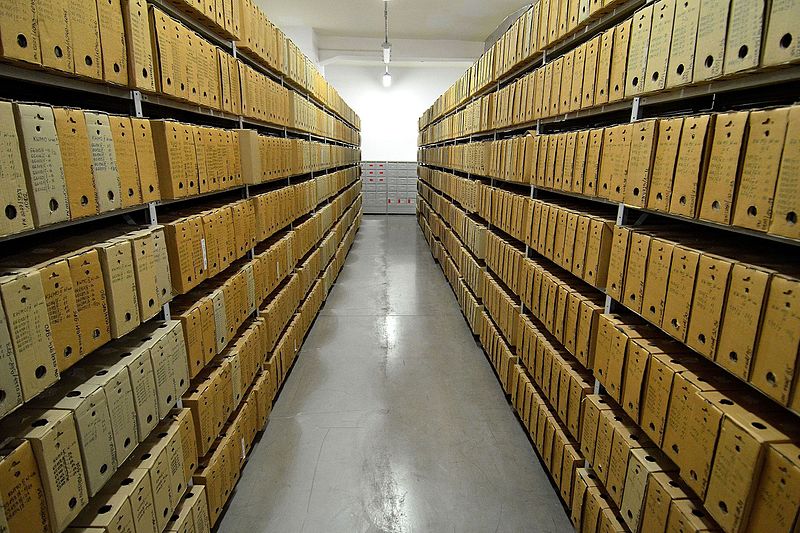

The IPN is a government institution charged not only with researching, maintaining archives and educating on Poland’s history of Nazi occupation and communist rule, but also with prosecuting crimes from those periods.

Its investigative division defines communist crimes as repressions and violation of human rights committed by communist regime officials between 1917 and 1990 that were illegal under Poland’s penal code at the time they were committed. They also include the falsification of documents by the state to the detriment of third parties.

A former member of the communist-era police militia, recently extradited from Croatia, has been indicted for his alleged involvement in a 'communist crime against humanity', the 1981 strikebreaking action that led to nine miners in Katowice being shot dead https://t.co/0eIHFqGfYu

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) July 9, 2019

Up to now, the statute of limitations for communist crimes had been 40 years for homicide and 30 years for other felonies, starting on 1 August 1990. The statute did not cover war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The IPN’s investigative division is currently looking into 431 cases of communist crimes. Over 300 have been classified as crimes against humanity, but the remainder had been at risk of expiring, reports TVN24.

The new legislation preventing that from happening was put forward by MPs from the ruling conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party. It passed the opposition-controlled Senate earlier this month then received overwhelming support in the Sejm, the lower house of parliament, last week.

“It is necessary but sad to note that, despite over 30 years passing since 1989, there are still matters to which we return with a feeling of shame that the justice system has failed in such cases to carry out an honest accounting of communist crimes,” said Senator Krzysztof Kwiatkowski, of the opposition Civic Coalition (KO).

As an example, he pointed to the unresolved case of an 18-year-old, Grzegorz Przemyk, who in 1983 was beaten to death by members of the Citizen’s Militia (MO), the communist-era police force, reports Dziennik.pl.

The move was also welcomed the Association of Veterans and Independence Organisations in Kraków.

“If there were no change in the law, then the Polish state would stop prosecuting the officers of the communist apparatus of repression who persecuted opponents of the [regime],” said the association’s spokesman, Jerzy Bukowski, quoted by Radio Maryja. “They would not be prosecuted for detentions, beatings, harassment, intimidation, firing [people] for political reasons.”

However, Krzysztof Persak, the former chief of staff to the IPN’s director between 2011 and 2016, argues that the amendment is mostly symbolic, as the number of cases being opened is falling as many of the perpetrators are no longer alive or fit to stand trial.

“The investigative department is having trouble finding new suspects who could be found responsible,” said Persak, quoted by OKO.press.

Bukowski, though, expressed hope that, even “if someone is over 90 years old”, he can still “get a conviction, which clearly shows that he is a criminal”, even if “he does not need to be put in prison”.

PiS and President Duda have made “decommunising” Poland a defining feature of their politics, and have pursued such efforts since coming to power in 2015.

Poland’s earlier approach to decommunisation had largely hinged on clarifying events. The country’s lustration laws do not punish citizens who cooperated with the communist secret police, but rather those who cover up their collaboration.

However, in 2016 PiS pushed for more severe measures, including lowering pensions for the former officers who served in the communist secret police, removing a number of “monuments of gratitude to the Red Army”, and ordering local authorities to rename streets and other public places commemorating individuals and organisations linked with communism.

City of Zamość removes plaque marking birthplace of Rosa Luxemburg because it 'propagates communism', contravening law requiring 'decommunisation' of public spaces. Left-wing parties protest 'act of vandalism'. More in English: https://t.co/FzGqvoUs7i https://t.co/AXfipmg0r3

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 16, 2018

The government and president have also sought to justify their overhaul of the judiciary and attempts to purge judges as part of these “decommunisation” efforts, claiming that not enough had been done to remove the influence of communists after 1989.

In June this year, Duda said that he and the government are “cleansing Poland of dirt” by removing “certain people” from positions of influence. These remarks echoed other recent comments about the need to “eliminate black sheep among judges”.

In 2018, Poland stirred up international controversy when it introduced another amendment to the law on the IPN which made it a criminal offence, punishable by up to three years in prison, to falsely attribute German crimes to the Polish nation or state. Following outcry, in particular from Israel and the United States, the law was later amended again to remove the criminal clause.

Main image credit: Adrian Grycuk/Wikipedia Commons (under CC BY-SA 3.0 PL)

Maria Wilczek is deputy editor of Notes from Poland. She is a regular writer for The Times, The Economist and Al Jazeera English, and has also featured in Foreign Policy, Politico Europe, The Spectator and Gazeta Wyborcza.