By Marcel Krueger

The northeastern province of Warmia and Masuria, once part of German East Prussia, is today firmly part of modern Poland, a region of lakes, forests and red-brick buildings popular among holidaymakers. But traces of its complex past are also on show.

Once a melting pot of nationalities, the region is a place where entire populations have been forced to flee, both to and from it. Strategies and opportunities for cultivating the memory of the people who have called Warmia and Masuria home, and the contribution they have made to its history, have varied. Visiting the region today, one can observe a number of initiatives to remember them.

Traces of history

Warmia and Masuria were once in East Prussia, part of the Kingdom of Prussia with its capital in Königsberg, now Kaliningrad in the Russian exclave that borders Poland. East Prussia itself became a German exclave after the First World War, before being partitioned between Poland and the Soviet Union after the Second World War.

Almost all the ethnic Germans living in the territories acquired by Poland were expelled by the postwar communist regimes, to be replaced by Poles who had themselves been displaced from former Polish lands now annexed by the Soviet Union. In total, some 12 million Germans are estimated to have fled or been expelled from their homes in this region, as well as other areas now in Poland, such as Silesia and Pomerania, and elsewhere, in the years following World War II.

The German political entity that existed as East Prussia before 1945 is forever gone, and the places where my family comes from today are Polish places with Polish names and a shared German-Polish history and identity. Despite some of the traditional narratives in Germany, this land was never “lost” – Warmia did not sink under the waves of the Baltic Sea after the Red Army marched through.

I still find the same lake that my grandmother used to swim in here, and in a mostly agricultural area like Warmia-Masuria even most of the key landmarks are the old German ones: the red-brick church towers and castle walls.

Łęgajny lake

Flag-waving narratives

In Germany, the topic of flight and expulsion was historically often dominated by the right-wing Homeland Associations of East Prussia, Silesia and Pomerania, the so-called Landsmannschaften, which formed the Federation of Expellees (Bund der Vetriebenen). They became politically and socially active as early as the late 1940s, even fielding a political party in the 1950s and ‘60s advocating the interests of the expellees.

Many of these associations still receive funding on a federal and individual state-level to this day, and in 1953 this support was even formalised by the Federal Law on Refugees and Exiles (Bundesvertriebenengesetz), which regulated the legal situation of ethnic German refugees and expellees from the east and their children.

I was never exposed to these associations – my grandparents, though from East Prussia and Pomerania, never had any interest in waving the flags of the “lost provinces”: their outlook was to the future. My grandmother Cäcilie never spoke ill of Poland and the Poles either. When she talked about her home country, she never specifically mentioned the nationalities here, maybe because she came from a family with dual identities where both the Polish and German language were spoken.

Or maybe because nationalities never really played a role in everyday life in Warmia before 1933. Even though she identified as German, her brother Franz more felt like a Pole, was active in the cultural work of the local Polish minority, and became a spy for the Second Polish Republic in 1935, for which he was executed by the Nazis in 1942.

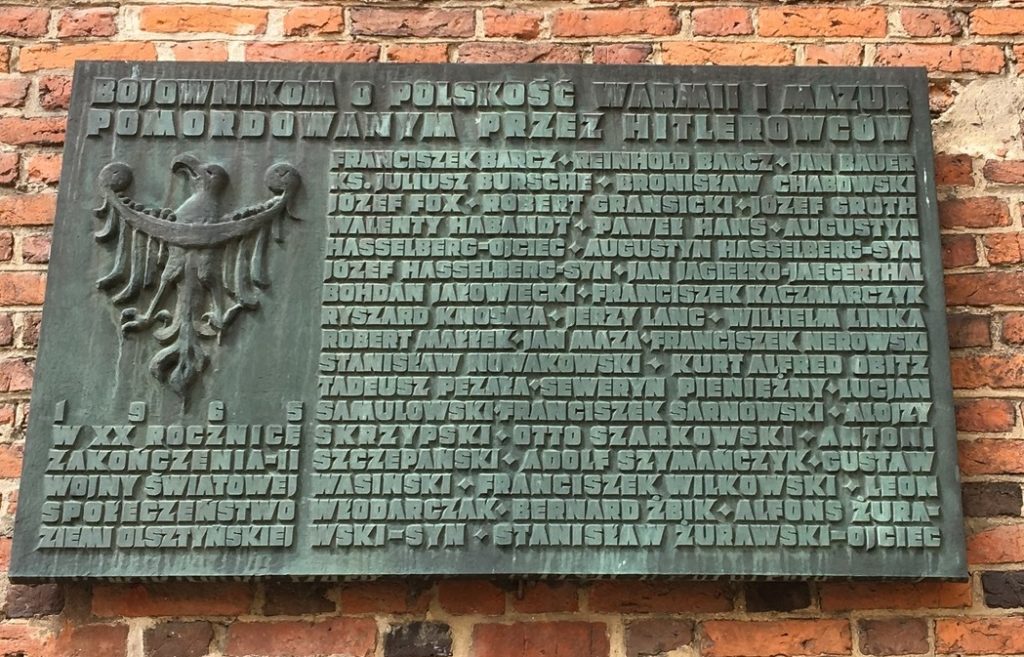

Memorial plaque to the “fighters for the Polishness of Warmia and Masuria” murdered by the Hitlerites, including Franciszek (Franz) Nerowski, Marcel Krueger’s great-uncle

Repressed heritage

And yet, the legacy of World War II, the subsequent colossal westerly shift of the Polish border, the flight and expulsion of the local German population followed by the resettlement of Poles, are a hard and difficult topic to talk about even today in the Warmian-Masurian Province – officially at least.

At first glance, the multicultural and multi-ethnic society, with its large Jewish, Polish, German and Tatar populations, changed radically as a result of World War II and the subsequent arrivals of the new expellees. But the level of (ex)change differed significantly between the different areas of former East Prussia.

Whereas in formerly Protestant Masuria the German population left in droves, in Warmia, where many people spoke Polish despite identifying as German and the majority of the population was Catholic, it was different.

Any attempt to preserve German heritage was repressed by the communist government. At the same time, the new Polish settlers had to adjust to the situation of forced settlement in a culturally and topographically very different “reconquered” land, as the communist authorities called the newly acquired former German provinces. They were equally deprived of any open memorial work for the homelands they had left.

Sowing the seeds of memorial

Only with the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 could memorialisation took place. Unlike with the aforementioned German groups, however, there was never a unified Polish approach to memory and remembrance supported by any government. So in the north of Poland it was always groups emerging from civil society that helped local communities to engage with their own and the German history.

One of these groups is the Borussia Foundation in Olsztyn. Borussia is a group of writers, artists and teachers founded in 1990 and dedicated to research of East Prussian heritage and cultural dialogue. In the late 2000s, they acquired the former Jewish Tahara house, together with the adjacent former cemetery, and extensively renovated it. Since 2013, the building, the first ever designed by famous local architect Erich Mendelsohn (1887 – 1953), has been used as a centre for intercultural dialogue, named the Mendelsohn House.

Borussia not only engages with the German past, but also organises a variety of contemporary cultural activities: the Mendelsohn house hosts free readings, concerts and exhibitions, and Borussia also organises youth camps bringing together young people from all over Europe for workshops around the themes of peace and reconciliation.

The Mendelsohn house in Olsztyn (photo: Wikimedia/Aniolek)

This does not mean that all is well: Borussia mostly relies on project funding for its operation that comes from EU programmes, the German Goethe Institute and other private foundations, and funding from the cultural ministry in Warsaw has been reduced to almost zero in recent years.

Remembering East Prussia

Strategies of remembrance for East Prussia have differed starkly in Poland and Germany. Maybe it is the direct, daily confrontation with the German leftovers and the communist attempt at creating an artificial Polish legacy that makes the people living here today engage with the land in ways long lost to the Germans, where everything that engages with East Prussia has to be pure and not damaging to the myth.

Like all former German Eastern provinces, East Prussia has its own state-financed museum, in the small town of Lüneburg in northern Germany. It was completely renovated in 2018, and its exhibition provides a portrait of the region as it was up until 1945.

There is a large area especially dedicated to East Prussian writers and artists like Siegfried Lenz or poet Agnes Miegel (a life-long supporter of the Nazis). Their words are displayed on the walls and posters, as are their books and pamphlets. Everything displayed here, however, is only in German. There is no mention of any of the Polish artists and writers that were active at the same time: there is no mention of, say, composer Feliks Nowowiejski or poet Maria Zientara-Malewska.

Across the border in Poland, however, Zientara-Malewska is mentioned, alongside other key figures of the history of Warmia, like Jan of Lis and Erich Mendelsohn, in the English-language visitor map produced by Olsztyn 2.0, a group of idealistic young social entrepreneurs formed of students and pupils from Olsztyn schools and universities that aim to positively promote their city.

For young people like these, the past is nothing to be feared, or to be abused for political gain – which is why they see no issues with mentioning German and Polish artists alike on a map aimed at English-language visitors. The positive aspect of the engagement coming from civil society is that it is hardly ever monothematic or in line with a government narrative.

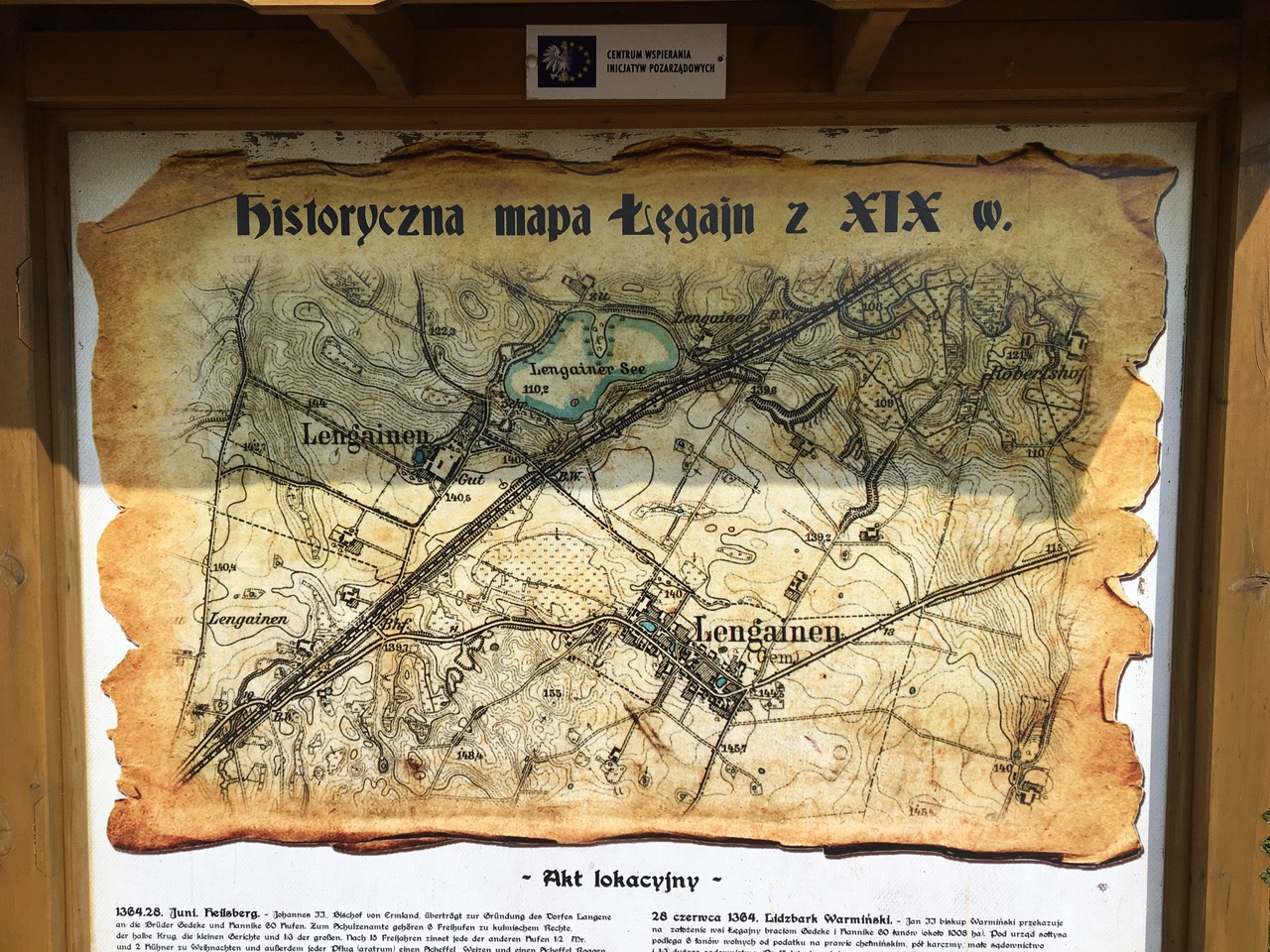

In the small village of Łęgajny, formerly known as Lengainen, where both Cäcilie and Franz were born, Polish-language information displays are dotted around, some on the main street next to a boulder commemorating the 650th anniversary of the village in 2004. They tell the history of the settlement since the Middle Ages, one even presenting a replica of a German map from before World War I carrying all the German street- and place names.

Historical map of Łęgajny/Lengainen

Community and conflict

All these signs have been installed by the local community, who have also created an arboretum, barbecue pits, a stage and a playground by the lake where my family used to swim. This is the home of a Polish community with grandparents from Vilnius and Czortków (today Chortkiv in Ukraine), but not a home that begins in 1945 or with some artificial Polish heritage construct prescribed by the government. No, it begins with the celebrations of villages that have existed in the same place for 650 years and where both Germans and Poles grew food from the rich soil and enjoyed the lakes in summer.

In the small village of Naterki, in the south of Olsztyn, business owner Janusz Dramiński operates a skansen (open-air museum) dedicated to agricultural machines, especially German ones produced in the area in the past. For him, this activity, which grew from a personal collector’s passion, has no political implication, and, like for the people in Łęgajny, allows him to connect with the peacetime society of East Prussia and their agricultural reality. Dramiński says:

The museum has many machines and tools that were used in agriculture: breeding, milling, blacksmithing, several decades or even a hundred years ago. I have great respect for the hardships the German farmers here went through because my family has a rural background, grandparents, parents and siblings. Those machines are the product of the hands of several generations of builders and constructors and deserve our respect just like the people that used them.

There are of course many conflicts. The current Polish government seems uninterested in supporting an open engagement with the multicultural history of Warmia and Masuria and has actively cut funding, so there is a chance that activities like those of Borussia will be further curtailed in the future.

If the government were to pursue the narrative that Warmia and Masuria are old Polish lands that have been “reclaimed”, they would be following the same argument as communist Poland. And yet accepting and emphasising the multiple identities and ethnicities of the region’s past belongs to a narrative that contrasts starkly with the Polish nationalist one.

Wojciech Smarzowski’s 2011 film Róża, set in former East Prussia in the months after the end of World War II, tells the story of Polish Home Army soldier Tadeusz, who agrees to help a German war widow on her farm in the region of Warmia. In one scene, he tries to clear a potato field of mines, and promptly detonates one by accident (he survives).

When I first started researching the (hi)story of East Prussia and my family’s place in it, I feared that I would be trying to clear a similarly fraught, albeit less obviously dangerous, minefield. But what I found was that many of the mines have already been cleared, and much good work is being done to cultivate that field.

At a grassroots and community level, and especially among the younger generation of Poles in Warmia-Masuria, the difficult history of the region is being preserved and remembered. There is plenty still to do and more things to learn about the complexity of identity and memory, on both the German and Polish sides, but remembrance of the past is providing a great deal of hope for the future.

Main image credit: Bundesarchiv/Wikimedia Commons (under CC BY-SA 3.0). Unless stated otherwise, all other photographs by Marcel Krueger.